The failure of the Canadian government to commit to the sustained, multi-year boost in funding for fundamental research recommended by a major report has generated much frustration in the scientific community.

Commissioned by the new Liberal government, the “Review of Federal Support for Fundamental Science”, led by former University of Toronto president David Naylor, was a response to the documented erosion of funding for field-initiated research projects since the late 2000s, under the previous Conservative government led by Stephen Harper.

The government has recently announced the creation of the coordinating committee recommended by the Naylor report to oversee policy across funding bodies. But the meetings and social media campaigns by scientists to push for the implementation of the report’s funding recommendations have, so far, been unsuccessful. Furthermore, the concurrent announcement of a C$950 million (£500 million) initiative to fund industry-led “superclusters”, also involving universities, has been viewed as a preference for directed, applied research over fundamental science.

Contentious debates on these policy issues have reinforced the traditional ideas that research can be squarely divided between “basic” and “applied”, and that there is a necessary trade-off between them. These ideas are still very common in the research community. But an emerging coalition of research leaders in North America believes that we have to rethink this supposed dichotomy. The HIBAR Research Alliance draws on well-documented research practices and science policy literature to make just this case.

Standing for “Highly Integrative Basic and Responsive Research”, HIBAR was launched this year by a group of Canadian and American researchers and academic leaders. According to the alliance’s consensus statement, its aim is to pursue both new academic knowledge and solutions to important problems. Key to this is to combine academic research methods with practical thinking, to engage both academic and non-academic experts; and to make contributions faster than basic research, but beyond the merely short-term applications that often arise out of applied research.

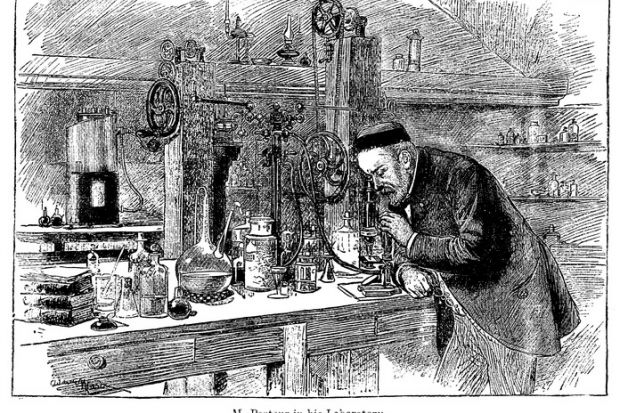

A touchstone for HIBAR is the idea of Pasteur’s quadrant, coined in the 1997 book of that name by Donald Stokes, former dean of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. Stokes superimposed three quadrants on a spectrum of basic to applied research. Purely applied work, involving only considerations of use, is illustrated by Thomas Edison’s inventions. Physicist Niels Bohr exemplifies research solely devoted to fundamental understanding. But there is also the middle quadrant, of which Louis Pasteur’s research into disease causation and prevention is the exemplar, representing research inspired by considerations of use but still seeking fundamental understanding.

Stokes’ discussion of Pasteur’s quadrant has proved useful in highlighting how investigators may address practical problems while still making important scientific contributions. Research falling under that model breaks with the assumption of a binary, wherein “basic” signifies high academic orientation and theoretical sophistication, and “applied” denotes a utilitarian purpose, often at the expense of scientific value.

However, many in universities, funding agencies and professional associations remain wedded to the conventional idea of basic research as a normative model. Academic incentive and reward systems overemphasise individual scholarly achievements in specialised research communities. Societal impacts and work carried out in collaboration with external partners to solve problems tend to be a sometimes grudging afterthought.

The result is that much research that can deliver positive contributions to society goes unsupported. Those pursuing it have to try to make it fit both established funding programmes that tend to emphasise either pure or applied research, and the preferences of peer-review panels. Even when they succeed in squaring this circle, professional credit for the results is often not commensurate with the work involved.

The gap is still wide in Canada between the core science policy debate and the grass-roots efforts to ease the route for researchers into Pasteur’s quadrant. Recent policy developments have only further reinforced the traditional binary understanding of research types. But if the likes of HIBAR can gain some traction, perhaps some of the current heat over the Naylor report might just be turned into light.

Creso Sá is professor and director of the Centre for the Study of Canadian and International Higher Education, University of Toronto.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: A halfway house for research

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login