It is no accident that we refer to higher education “systems” – that is, a “set of things working together as parts of a mechanism or interconnected network; a complex whole”.

The label applies most obviously to the broad range of institutions occupying different spaces within a national system, whether that relates to location or disciplinary mix or university mission.

But the systemic nature of higher education also extends well beyond institutional diversity: there needs to be harmony in all sorts of areas, from modes of delivery to the balance of teaching and research, undergraduate and lifelong learning to higher education funding. All are sensitive ecosystems, and need to be treated as such.

The last two in this list – skills and funding – are the focus of particular debate at the moment, as governments grapple with how to sustainably finance higher education and how to shift the emphasis towards the skills and lifelong learning agendas they increasingly favour.

On the sustainability point, the funding systems in many countries seem increasingly broken.

That can be viewed through the lens of affordability in the US, resource constraints in publicly funded systems or the inflation trap that is turning England’s tuition-fee model from a finance officer’s dream 10 years ago to a nightmare today.

She is not the first to sound the alarm, but it was still striking to hear Irene Tracey, the new vice-chancellor of the University of Oxford, express astonishment at the parlous state of the funding system recently.

Speaking at a seminar organised by the Higher Education Policy Institute and AdvanceHE, she said that “the one jaw-dropping thing I’ve learned in my first three months is just how perilous the higher education sector is financially”.

While the specifics of institutional crises such as that unfolding at the University of East Anglia will vary, the broader point about systemic flaws was made equally starkly in a recent opinion piece by Ian Walmsley, provost of Imperial College London.

“The business model for higher education is not adequate to support the country’s long-term ambitions,” he said, adding that “no one should assume the outputs of universities will continue regardless of inputs”.

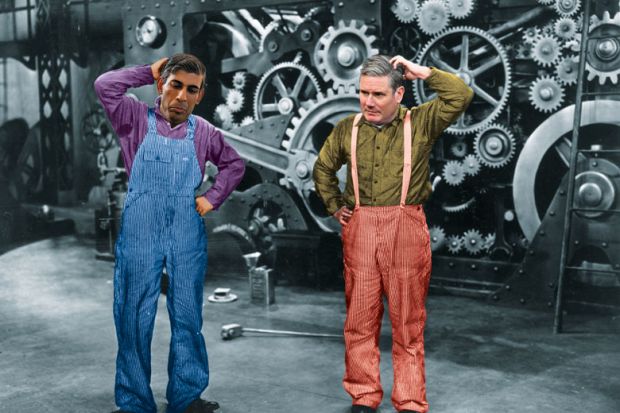

None of this is new. But could it be that there is some sort of consensus emerging that this is a problem that has to be fixed, and that this will only be possible if there is a cross-party approach (Tracey called for a “root-and-branch” review) that removes the future of this strategically crucial sector from political point-scoring?

Any such review would have to take in funding on a system-wide level, including governmental priorities such as degree apprenticeships and lifelong learning, both of which are explored in our features and opinion pages this week.

One of the threads running through these pieces is that, despite these being areas of particular focus for politicians, neither has its financial model fully nailed down.

In the case of degree apprenticeships, the system introduced in the UK under the apprenticeship levy (which provides a tax-based funding stream direct from companies over a certain size) has provided a financial foundation for the qualification.

However, we hear from universities that find the reality much harder than might be supposed, with the cost of designing and delivering programmes and the unpredictability of student intakes (particularly when working with smaller employers) among the issues raised.

Similarly, when it comes to lifelong learning, the UK government has set out the Lifelong Loan Entitlement as a flagship (future) policy. However, as Hepi director Nick Hillman says in a recent blog, “it will be up to universities whether to redesign their courses to make them eligible for the LLE” and “many institutions may not think it’s worth the candle”.

A similar warning is made in an opinion piece by David Spendlove, associate dean of humanities at the University of Manchester, who warns that such modules might prove to be loss-making and would impose considerable additional burdens on staff.

Like others, his conclusion is that, however good the idea, in practice there is a lot of work to be done if it is to stack up.

Perhaps it is inevitable with a system as complex and dynamic and politicised as higher education that a new funding review will be needed every decade or so. In any event, we are long overdue the next one.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login