A child’s mind is a precious gift. And China’s education system is a magnificent achievement. As an adviser to a small after-school programme in Beijing for high-achieving students, I’m often delighted by the curiosity and creativity of Chinese students in primary and middle school. However, I am just as frequently distressed by the withering of that intellectual sparkle once they get to high school and university.

The reason for this dismal phenomenon, it seems to me, is very simple. It is the contagious marketing meme that preparing young people to win admission to a top US or UK university is more important than preparing them to flourish once they get there.

I don’t blame the universities for requiring overseas students to sit SAT, TOEFL or IELTS tests. Measuring students has merit. And I understand that some students need extra help. A weekend or holiday programme reviewing what to expect on the test makes sense. But worried Chinese parents are forcing these courses on their children years before they make their applications – even though test scores are valid for only two years.

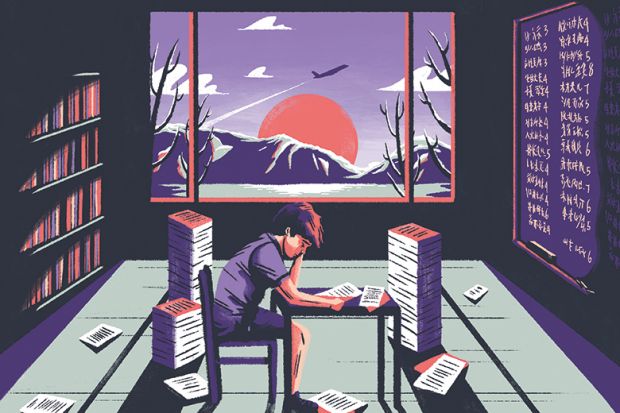

In my programme, we have had parents ask for TOEFL training for their seven-year-old son (we said no). And several of our first-year high school students took a 14-day, 9-to-5 SAT programme during the last winter school holiday, rather than enjoying a break and travelling with their parents. By the beginning of spring term, when they should have been rested and ready to learn, they were exhausted. The light in their eyes had gone out.

I find all this particularly curious because, as a business owner and management consultant, I consider university to be a tool, a stepping stone to an adult career, not a goal in itself. Moreover, the irony is that endless test prep isn’t even the most effective university application strategy. Years of memorising the answers to previous tests, over and over again, inevitably makes young people miserable, dull and mediocre – and damages their interest in learning.

In the past three years – especially since the SAT was reformed – the students I’ve observed who’ve scored highest are those who read great literature and important articles about science and world affairs. They take part in the global conversation instead of taking SAT prep; they write their own application essays, and they are accepted on early decision by whichever top US institutions they apply to. They have exactly the “scholarly aptitude” that the SAT is supposed to identify.

Those students who take long test-prep classes generally get lower but still respectable SAT and TOEFL scores. However, they fall down on their application essays because they have little to say. Nor can they show much of the evidence of achievement or community involvement outside school that would convince an admissions tutor that they will enhance a diverse student body. So when they apply for early decision, they are more often deferred to regular admissions, or just rejected.

A couple of stories highlight my concerns. A ninth-grade middle school pupil was taken by her mother to a large TOEFL test-prep “academy”. The girl’s vivid and expressive prose, to me, indicated a deep talent, but a young foreign salesman said that she wasn’t trying hard enough. She needed to seriously change her style and acquire much more vocabulary – for which, of course, she needed a long period of study at the academy. On our programme, this student had just started a study of Thomas Mann and E. M. Forster, but it was impossible to convince her mother that this might be a better path to a top university. The meme had done its work.

In another memorable case, an eighth-grader told me that she was learning TOEFL “techniques”. I gave her a sample test and asked her to show me one. She immediately went to the first question, underlined a couple words, then went to the first paragraph of the text and tried to find those words there. I asked her why she didn’t read the text first. “Because, at our age, we don’t understand it,” she answered. And why should she?

So what’s going on? Well, there is a high degree of Tiger Momism in Beijing: a city that many now consider the centre of the new Eurasian empire. Its cognoscenti and newly prosperous denizens determine bragging rights partly on the basis of their offspring’s test-prep scores.

Moreover, competition for a prosperous future is fierce in a country of 1.4 billion people. If you aren’t well connected, sending your children to a renowned foreign university is seen as a good option – especially if you believe, as many Chinese do, that the competition for admission is less intellectually endowed and prepared. Seven days a week of study and one week a year of vacation are the price to pay for a good job: tears now, joy later.

So this is just the Chinese way, then? Not really. Some memorisation is necessary to learn any subject, but memorised vocabulary without a social or geographical context is quickly forgotten once the test is complete. The Chinese way has always involved a love of and respect for genuine learning.

Moreover, the modern Chinese way has been to proceed on the basis of what works and what doesn’t. Some test prep may help to improve individuals’ university admission scores, but bingeing on it will stymie the country’s future development.

China needs inventors – not just imitators and innovators. Innovation can mean designing a better soft drink can, or taking a few calories out of a McDonald’s hamburger. Invention means creation. And that comes from thinking deeply and reading widely – before, during and after university.

Bob Fonow is managing director of consulting firm RGI Ltd, based in Beijing and Virginia, and the non-executive chairman of an education services company in Beijing. He has long experience in corporate turnaround and US government strategy.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Curiosity killers

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login