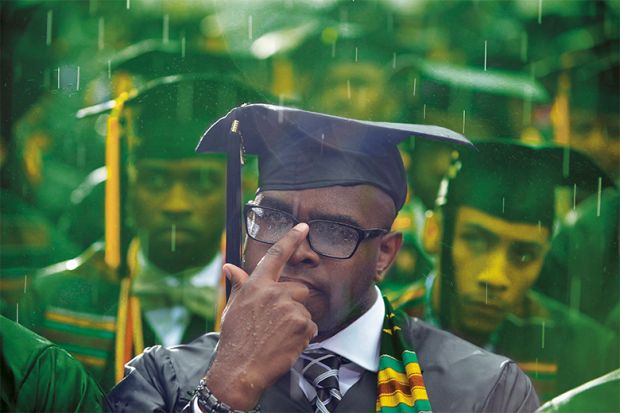

Billionaire Robert F. Smith’s recent pledge, during his commencement address at a liberal arts college in Atlanta, to pay off the senior class’ student loans understandably grabbed the headlines. But among the jubilation of Morehouse College’s class of 2019, I am pretty sure that I also detected a note of sheer relief.

That turned my thoughts to my own students at another historically black institution not so far away, Tennessee State University in Nashville. In all likelihood, there will be no billionaire ex machina on their graduation day: no get-out-of-debt-free cards. Perhaps they will even experience an element of buyer’s remorse at having paid such a lot of money for a degree in history that offers no straightforward route into highly paid employment.

Few of us in the humanities like thinking about our jobs in this way. Our grand ambitions almost always defy a simple cost-benefit analysis. I have argued for years that by foregrounding human beings and all their many complexities, a humanities education makes students more comfortable with ambiguity and nuance. In a world becoming more polarised by the day, where complicated issues are rarely treated as such and opposing voices are almost always reduced to caricature, this is more important than ever. A society that loses the humanities, I fear, loses everything.

But Smith’s gift is a reminder that we cannot escape the more practical considerations that many of our students confront in pursuing an education. This is underlined by the enrolment figures. US students’ interest in the humanities predictably dipped with the financial crisis of 2008, but while the economy has since rebounded, interest in the humanities has not.

Pragmatic priorities seem to be carrying the day still, and the rising cost of tuition may be an important factor. Student loans are cumbersome things and affect everything from the house you can buy to the vocational risks you can take. Follow the Morehouse students alongside their less fortunate peers who graduated in other years or from other liberal arts colleges and track whose lives turn out better: the comparison will surely bear fruit for those advocating for free college.

As an adjunct professor applying for jobs both inside and outside academia, student skittishness about majoring in the humanities is not surprising to me. I prize the skills that we develop, but the job market in an increasingly specialised economy has other ideas. More vocationally specific skill sets are often tough to beat. Students are right to be concerned about this. And while many in the liberal arts remain conveniently confident that the pendulum will swing back in our direction eventually, I believe that we must face up to this new reality if our subjects are to thrive again.

In his 2018 book What School Could Be, another billionaire businessman-turned-philanthropist, Ted Dintersmith, posits a symbiotic relationship between the economy and education. As one changes, so must the other, he argues, because if it is to work well, education needs a clear purpose for students, however that is defined. And while many of his examples are from scientific disciplines, he stresses that he does not consider the humanities to be a vocational black hole. However, for “liberal arts faculty who view marketing as undeserving of ivory tower status”, Dintersmith offers a stern admonishment: “Your field needs it.”

I think he may be right. When I debuted my carefully planned and academia-approved courses several years ago, my students told me on day one that they considered the whole exercise not necessarily uninteresting or unpleasant, but entirely irrelevant. I disagreed, fervently at first, and if the humanities were doing fine, I probably would still be doing nothing but pushing back.

But the crisis made this stance feel absurd. So I asked them to elaborate on their criticisms. That prompted me to radically redesign my introductory history classes. Now I open them by citing various business leaders, public intellectuals, entrepreneurs and the like, discussing their jobs and the various skill sets they required. The subsequent course is organised around developing those skills. In this regard, the economy gives as much as it takes away, since, as Dintersmith notes, its emphasis on higher-level skills is highly compatible with the longstanding goals of a humanities education.

My reconfigured classes are not vocational training: far from it. But they do highlight their many practical applications. This approach may make more sense in particular settings (I teach only introductory courses) and at specific institutions, and it is just one among countless and even diametrically opposed options for how we can reimagine our course offerings. Yet in my case, the changes I have made have improved my classes by almost any measure – starting, most importantly, with student interest and engagement.

So I hope that the laudable prospect of improving the value of college by making it cheaper does not diminish the urgent efforts that are being made to bolster the other side of the value equation – especially given that academia typically offers few career incentives to rank-and-file professors to care about such issues.

Whoever ends up footing the bill for college, our future will still depend on being able to convince others that an education in the humanities is worth paying for. And if our lack of success with students right now is any indication, we need to do better – whatever that ends up meaning.

Kevin Vanzant is a history instructor at Tennessee State University.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Face up to employability fears

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login