As travel bans disrupt international education and the global recession squeezes public and charitable funding sources, universities stand to lose revenue while costs rise.

But there are also opportunities. It’s common knowledge that when the economy thrives, university enrolments fall, whereas a recession causes enrolments to rise. But what institutions and governments need to know is what types of enrolments are sensitive to the economic cycle, by how much, and how soon. Could a rise in domestic enrolments mitigate the losses from international students? Data from New Zealand provide some hints.

In 2009, as the global financial crisis (GFC) loomed, the country’s Ministry of Education released an analysis of how enrolments in post-compulsory education tracked the economic cycle following the severe recession of the early 1990s.

That recession saw significant increases in retention in senior secondary school and in tertiary education. Moreover, there was a strong association between higher school retention and increases in participation in bachelor’s study the following year, presumably because there were more eligible young people.

Meanwhile, the progression rate from bachelor’s to postgraduate qualifications also matched changes in the unemployment rate as graduates delayed entry to the labour market.

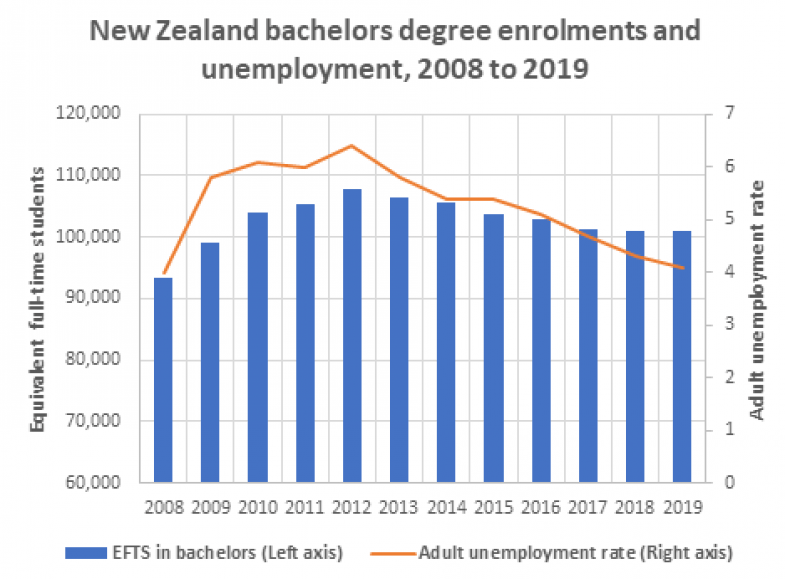

Following the GFC, bachelor’s enrolments kept rising, peaking in 2012, when unemployment also peaked, before returning to stability as the unemployment rate fell below 5 per cent. In the early years of the recession, enrolments tracked the unemployment rate closely.

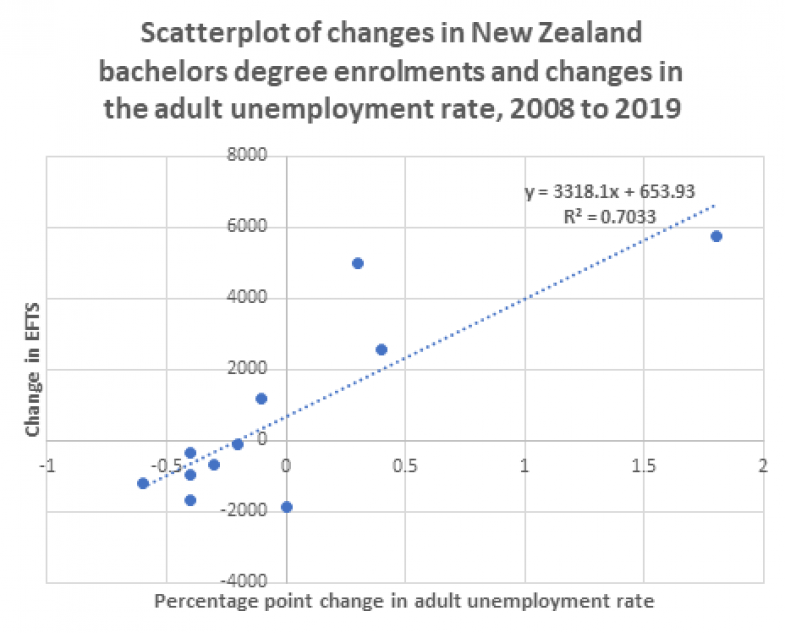

In addition, there is a high correlation (0.84) between changes in the unemployment rate and changes in enrolments. Analysis suggests that changes in the unemployment rate explain 70 per cent of the variation in the enrolment change. A one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate is associated with nearly 4,000 more full-time equivalent students.

However, it’s dangerous to jump to conclusions.

One reason is that recessions all have different causes and, therefore, different speeds, severities and impacts on the various employment sectors. The recession of the early 1990s had three main drivers: a major reallocation of resources as economic liberalisation led to the closure of uneconomic industries; downturns in New Zealand’s main trading partners; and a fall in demand caused by high real interest rates and reductions in government spending. This saw unemployment reach about 10 per cent.

The GFC was different. Failures in the world financial and banking system led to falls in asset values and, therefore, demand and investment. Unemployment jumped sharply in New Zealand, reaching 6 per cent in 2010 and staying there until 2013.

The recession we face now is different again. Lockdowns had an immediate, acute effect on trade. Industries such as tourism and hospitality face a protracted loss of business. Asset prices and wealth will fall. Demand collapsed fast but will recover slowly. Unemployment is already rising, more quickly than in the GFC. So we can’t assume that what unfolds will mirror the GFC recession.

In particular, we can’t assume that the big increases in participation rate as the unemployment rate rose will be maintained if the Covid-19 recession leads to unemployment growth as sharp as the most dire forecasts. Many people who are leaving school or losing jobs don’t have the aptitude or inclination for study.

Moreover, the relationship between participation and unemployment isn’t static. Changes in funding rules, student financial support policy, admissions criteria, school retention and immigration will have affected the higher education participation rate.

And while there appears to be a strong relationship between the economic cycle and enrolments in certain types of programme, overall tertiary enrolment appears less sensitive to the cycle. Applying this sort of analysis to total enrolments gives a correlation coefficient of 0.56 – a positive but moderate relationship – while changes in unemployment explain only 32 per cent of the change in full-time equivalent students.

So while history gives an idea of the effects on tertiary education enrolments that we are likely to see post-Covid, quantifying the effects is a less certain exercise. Still, for those trying to chart a course through the turmoil, it’s probably as good as they will get.

Roger Smyth is an independent consultant and adviser on tertiary education. He is the former head of tertiary education policy in New Zealand’s Ministry of Education.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login