Those who care about the future of the academy should take note of recent events at Portland State University, where an academic is threatened with sanctions for his involvement in a publishing hoax designed to expose lax standards in humanities disciplines that focus on gender, sex and racial identity.

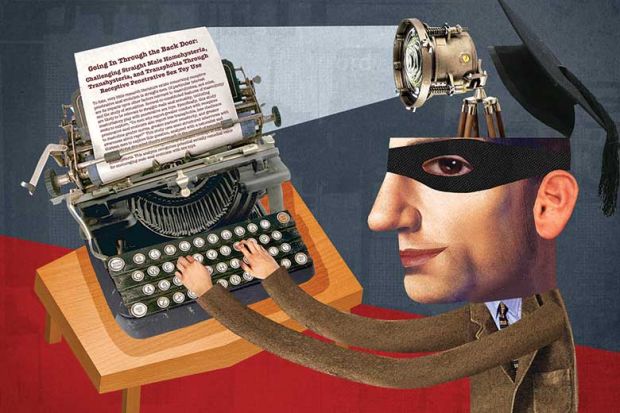

Peter Boghossian, assistant professor of philosophy at Portland State, is one of three protagonists behind the so-called Sokal Squared project, which sought to explore concerns that too much of the published scholarship in what is provocatively termed “grievance studies” is poorly researched, incoherent and ideological.

To this end, the researchers wrote and submitted hoax papers – none based on actual research and several resembling overt parody – to an array of peer reviewed journals. In doing so, they emulated the style and approach of standard papers published there. In some cases, such as the now iconic: “Rape Culture and Queer Performativity at Urban Dog Parks in Portland Oregon”, the manuscripts were so absurd as to strain the credulity of any scholar paying attention. The researchers’ goal was to see how many papers might be reviewed and published and then to bring critical attention to the problem by revealing these as hoaxes and retracting them.

Their effort prematurely terminated when it was exposed by a journalist – whose account garnered worldwide attention. This was obviously embarrassing to the journals, their editors and the related fields. But instead of reflecting on the implications of the hoax for their approach to scholarship and committing to greater rigour, the response was mainly defensive. Although any discipline whose standards are questioned might react similarly, these fields – steeped in postmodernism and critical theory – are legitimately vulnerable to criticism of their standards.

Efforts to punish Boghossian for his involvement were soon initiated. As the sole hoaxer with a faculty appointment – his non-tenure-track position involves teaching critical thinking and moral reasoning but not research – he alone was subject to rules and regulations of the academy. When the hoax went viral, some colleagues published a stinging anonymous critique of his involvement, and he received numerous abusive attacks and threats to his safety.

But the most serious threat to his long-term well-being came from his university administration, which launched two ethics investigations. The first raised the serious claim of research misconduct, defined as fabrication, falsification and/or plagiarism. Typically resulting from sociopathy or misguided efforts to promote faculty careers through deception, such misconduct incurs severe consequences, including termination.

However, Boghossian and colleagues undertook their fabrication not to mislead readers but to critique the publishing process. So although it is understandable that this charge of misconduct via fabrication was raised, failure to take into account the intent of the regulations means that it falls flat. Boghossian deserves a timely exoneration on this count – yet, informed of the investigation in mid-October, he has yet to be told its conclusion.

A second investigation involved a claim that he failed to engage required procedures for research involving human subjects. Academic institutions in the US are subject to a federal regulation called the “common rule”, which seeks to protect the subjects’ interest by requiring research organisations to establish institutional review boards (IRBs) to oversee and approve human studies. By not seeking its approval, the Portland State IRB concluded that Boghossian violated its rules.

How should we view this claim? Five interrelated issues must be considered. First, should the hoax be considered “research”, as opposed to a journalistic investigation or parody performance art (think Sacha Baron-Cohen)? Second, if it was research, was it human subject research, with the hoaxed editors as subjects? Third, did Boghossian’s faculty position give Portland State authority over the activity? Fourth, if the activity was considered human subject research under prevailing rules and PSU authority, should Boghossian have sought IRB approval? And, fifth, if the answers to the previous four questions are affirmative, should informed consent from the subjects have been required?

My discussions with experts on human studies reveal that most view the hoax as human research under PSU aegis, requiring IRB approval, but that most IRBs would have approved the request and waived informed consent. Several of these points are debatable, especially whether the project should be considered research, but I will not further elaborate on these. Suffice to say that even if it is determined that IRB procedure was violated, the failing was inadvertent and of minor significance. Any sanction should be limited to pointing out the error and requiring procedural education should Boghossian undertake future research. Should more severe sanctions be levied, this would suggest the influence of objections to the project’s conclusions rather than concerns over its technical violations of university policy.

Attention should then return to the primary issue: implications of the hoax for the research fields in question. These fields could have much to offer, and the chagrin of those working in them at being labelled “grievance studies” is understandable. But if scholars attack the messenger rather than address serious concerns about shoddy peer review and insufficient scholarly rigour, they will further undermine the disciplines they seek to defend.

Jeffrey Flier is a Harvard University distinguished service professor and former dean of Harvard Medical School.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Exposing lax publishing standards is not research misconduct

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login