This morning I gave all 50 of my students A grades. Then I took a shower, danced, ran to the beach, swam and cried tears of joy. For the first time in years I feel like a real professor again, my work vital, alive and human.

After 30 years of self-assured professionalism I’ve experienced a crisis of faith. As a young professor, I believed in systems and fairness. Now I don’t. Grave moral responsibility to grade students without having real authority to use my own judgement has weighed on my mind, robbing me of sleep and health. Time pressure to prepare for three other modules this semester was the last straw.

But do my students all “deserve” straight As, you ask. My answer is that I don’t know any longer. Much ado is made about the “student experience”, but in reality it is one of technological dependence and dystopian performance anxiety. We meticulously craft clear assignment briefs, clear rubrics and model answers. And we allow students to test submissions against Turnitin, tweaking them until they “pass”. The emergence of ChatGPT, summarising tools, advanced Grammarly features and Copilot-style computer code “support” will only further undermine the human values we purport to hold.

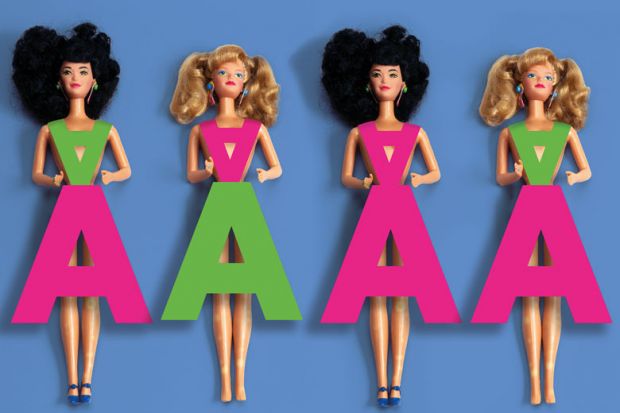

The question I might ask back is why it matters whether my students deserve straight As. How did we get so hung up on judgement, as if universities were courts of law and education primarily a process of justice? The result is a fear of straying from the specified formula for academic beauty that resembles the accounts by Naomi Wolf or Susie Orbach of female body anguish. Like a row of Barbie dolls, each student submission mirrors the model answer in insipidly perfect cookie-cutter prose and code snippets. How am I supposed to differentiate them? Keyword count? Referencing style? Perhaps by simply printing them out and weighing the reports, as my own professors (presumably) joked that they did?

The more we try to make grading “fair”, the less it serves anything even resembling a purpose beyond make-work activity. Yet that doesn’t stop us trying. Why? Because knowledge is no longer the product of the “education industry”. Data is. Specifically, individualised psychometric and performance data for use in professional gatekeeping. Students know this, so they’ve become obsessed with their extrinsic “permanent record”. They are no longer the least bit interested in what I have to say or give as a teacher. They are not interested in my formative feedback. They hang only on the grades that I give them.

Some professors have lashed out, making their students scapegoats for “the system” and failing the entire class for “academic misconduct”. But students cannot be blamed for acting rationally. It is we, the faculty, whose misconduct must be put right. We must rebel against the idea that years of academic effort and, indeed, the very worth of a person are reducible to their final grade.

My rebellion is not entirely novel. For millennia, education functioned without individual measurement. And over the past 20 years “ungrading” has become something of a movement, especially in US humanities. But although common motives relate to gender, race and class concerns, my own stance is grounded in science.

My fields include cryptography and signal processing. For us, a hard problem is that it’s near impossible to grade computer code or judge its originality. There really is a right answer and, if students copy the same model, change a few variables and values, all I can do is pedantically waste time looking for imaginary faults.

More generally, though, there is overwhelming evidence of psychological damage caused by the constant anxiety associated with competitive peer-comparison and obsessing over inconsequential rules. This is wholly in conflict with the creative, equitable relations we so desperately need to allow students, once again, to focus on learning.

It is also in conflict with employers’ interests. Firms that outsource their recruitment to universities are by no means necessarily recruiting the most innovative minds. More likely, they are recruiting the most obedient and/or the most cynical, the most willing to second-guess algorithms and demand better grades.

The emotional burdens imposed by grading are similar to those borne by social media content moderators. Grading fosters hostile relations with students and racks teachers – who all feel grading’s unfairness – with guilt and self-conflict. Nor can grading be fairly automated. Although more consistent than humans, algorithms are no more reliable or accurate. And while humans can acknowledge or challenge hidden biases, digital systems invisibly encode and entrench them.

The consequences for professors who “ungrade” vary. Some are heralded as progressives and promoted to pedagogical leadership. Others are fired. But it is important to observe closely who pushes back against ungrading and why. That’s why I’ve undertaken this experiment: not so much to measure what my students learn from getting A grades (the point of the experiment is not to) but to observe the response of the institution.

I may well get fired, too. But if I do, I’ll be happy that my low-cost, high-impact research might be enlightening for school-leavers thinking of entrusting their ongoing “education” to institutions that have long since ceased to take that mission remotely seriously.

Andy Farnell is a visiting and associate professor in signals, systems and cybersecurity at a range of European universities.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login