After two decades of moving up the academic career ladder, working with thousands of students and winning teaching awards for it, writing a book, and chairing projects (and winning awards for those too), I cry at work every day. Driving to college, I want to steer my car into a tree.

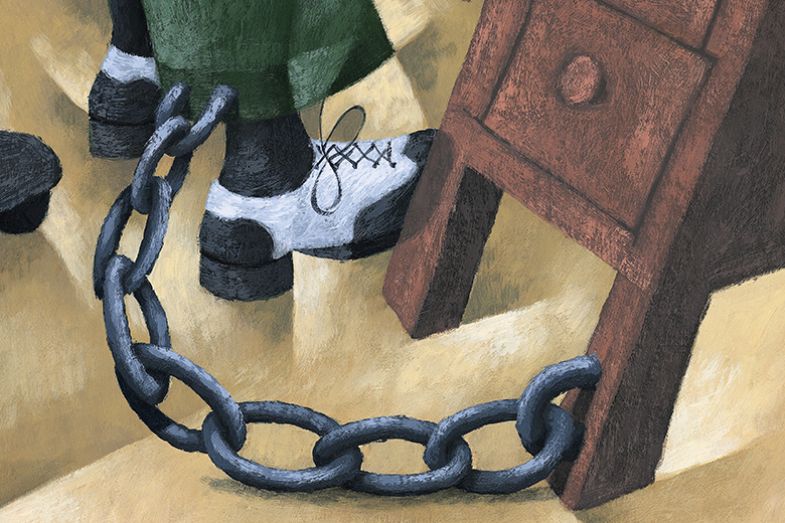

That’s not hyperbole; the urge to destroy myself is a part of my commute. I’m raw, diminished. I fear I am toxic to my colleagues and students. I’ve had to take unpaid leave to try to hold myself together. How did I get here?

I’m a tenured professor at a well-regarded US community college. Such institutions are romanticised in some American minds as places where faculty, free from the stresses of competing for research funds, can focus on preparing promising undergraduates for a smooth transfer to university or into a well-paid trade. Poised, elegant First Lady Jill Biden’s background as a community college professor only adds to the sense of these institutions as low-stress, feelgood environments where educators and students thrive.

In reality, my institution – one among many – faces myriad problems, presided over by a demeaning leadership culture of yelling, bullying and promising to consult faculty “next time”.

Because faculty operate under a constant time crunch, battles must be picked carefully. A typical week consists of 15 hours in the classroom, four hours in meetings, 10 hours grading (how fast can you thoughtfully respond to 130 essays?) and six hours prepping for class and tutorials (how fast can you write an agenda or lecture?). That’s 35 hours. It leaves only a few stray moments for updating announcements, assignments and lessons in the learning management system, not to mention inputting into the other needy databases things like student attendance, demeanour and drive.

Then there are the special initiatives. Art, civic engagement, social justice, a common read, universal design and study skills are just some of the extra projects that staff should now undertake. Add “volunteer” work with the Honors College, which supports exceptional students, the diversity council, the curriculum committee and leading special projects. The notional 40-hour week we meant to work seems forever lengthening.

The five hours of student time each week is also critical. The retention rate at community colleges nationally – that is, two-year associate degrees and certificates – hovers around 45 per cent, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. Retention rises significantly, however, when students are offered help before they ask. Research tells us that many come from a space of deprivation, in which they have learned not to ask for help. In a faculty-led initiative, several of us attempted to see as many new students as possible at the beginning of each term. I’ve shared the results of these collective efforts at a national conference. But even if we push them into small groups, we only manage to see about half of them.

Faculty suggested that we drop down to a lighter course load, which would free our time and alleviate many low-enrolment concerns. We were ignored. Furthermore, new special projects were instigated, with one requiring extensive curriculum revision. Here’s $500: make time.

Meanwhile, the classroom consequences of national policy have yet to be reckoned with. When colleges across the country removed remedial, non-credit-bearing courses from their rosters, the idea was to integrate remedial tactics into credit-bearing courses. Our trustee board wax lyrical about the value of “integrated remedial education” and the social mobility it apparently delivers. On the ground, the expertise of remedial professionals was actively ignored and derided by those who worked only in passing with this at-risk population.

As a result, I was asked to teach freshman composition from a common syllabus, designed to fold in the formerly remedial, to the handful of students who could make it to our pre-vaccine face-to-face class. An excerpt from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics seems a great place to start a college path: developing skills of all sorts is bound up in definitions of a good life. However, the students don't have the bandwidth to care. Aristotle means nothing them. Through the grapevine, I learn that Jill Biden has been using Trevor Noah’s Born a Crime memoir when she teaches this class. It is a far better choice for a group so afraid for their futures.

What is education for? It can be debated at Columbia University. For most at community colleges, the subject is settled. It’s for work. Finding work that will ensure a certain level of health and well-being must be paid for in America. One woman with two children learned, during a classroom research experiment, that she was making more money at her current job than her intended career promised. She left college in the middle of that class.

There are also widespread misconceptions about who we teach in community colleges. A freshman classroom will contain only a smattering of the expected 18-year-olds, some staying close to home, others escaping from rough inner-city boroughs, some lured to continue playing sports. Single mums and single dads are common. They are the formerly incarcerated, ex-military, trans-identifying, refugees, Indigenous and high-functioning autistics. They span every skin shade, most religions and all skillsets. When they come together in a community college classroom, it can be magical.

Increasingly, though, it can be chaos. The sad fact is that only 28 per cent of community college students will graduate with some kind of degree within six years, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics.

Students do not know this coming in. We should tell them. Tell them that attending college with a full-time job, two kids and no spouse requires a significant support network. Tell them that we offer no plan B. Tell them that if they can’t read a newspaper article, they won’t be successful. Tell them that the pirated wi-fi from the neighbour is insufficient for online work and that working on a smartphone with a shattered screen isn’t the same as sitting at a computer. Instead, they learn these things from experience, once they’ve paid.

Unfortunately, these students destined to fail can also have a negative effect on others. Excellent students can now take foundational college courses in many high schools. But this means that those earnest students who may have brought on their classmates are replaced in colleges themselves by those who are disconnected and thereby give permission for others to disengage. These students advise each other, whispering that they will still pass even if they don’t read assigned material or go to class.

On a rare occasion, they’re right. But not often. I explain that learning is an active enterprise. How can you learn if you don’t show up? Show up for the reading, show up to the class, show up for notes and the review of those notes. Your friends who would have you think college is easy are lying. You need to be devoted. You signed up, so be present. Be present, as if learning were part of your religion.

Lesson plans for group teaching dissolve when only four students show up. If those four aren’t prepared – and they aren’t, though one might be – the first half of class has to be spent doing the homework so that some abbreviated version of the lesson may still be embarked upon later. It isn’t college, but we’ll go through the motions and pretend. The students suffer but, after all, don’t know what they are missing.

I do, though. And I believe that we should also address the moral injury suffered by staff who know their employers are taking money from people who can’t possibly be successful in a course. One young woman bounced between refugee camps in Kenya and Indonesia before landing in my city. She glares at me in class; likely, this isn’t the kind of English class she expected. My college isn’t offering any ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) courses at the moment.

We understand, as an industry, that first-generation students are at risk, largely because they lack certain supports. Many colleges do their level best to provide childcare centres, food banks, places to pray and counselling services. Teachers are required to track students: being asked to state the last day a student who earns an F attended a class obliges us to take attendance.

Further, we note reasons for absences: Sasha is out because she’s having a C-section (don’t try to make a whole new person and go to college at the same time, I wanted to tell her). Sybill’s family has Covid-19 and she is caring for her little brothers. Jackie is out with headaches, one of the many pleasures left by the bullet that put her seven-year-old self into a wheelchair. A deaf student left in the middle with a panic attack, so I will post the video of last year’s lecture for him because it is already captioned. I hope the other absentees will watch it, too.

With between 100 and 130 students per semester, I find myself on any given morning typing words of comfort before 8am to individuals who have been beaten by abusive partners and have to miss class to visit the emergency room, or who have been in a car crash, or whose child is very sick.

Even among students aiming to transfer to the Ivy League, drug abuse is another unacknowledged problem. I’ve known several addicts over the years, the promising or not-so-promising brought lower than one is willing to imagine, and then shamed into the bargain. On my shelf, I have a particular oversized novel that contains a dedication from a formerly incarcerated honours student who overdosed. Students' stories can be impossibly heavy, yet my colleagues and I carry them. Never do we address the reflective trauma of daily community college teaching.

When Covid drove everyone online, it was especially challenging. Quickly, though, we came back, fully face-to-face before the vaccine was available, dizzy from learning new remote-teaching skills and creating online material we then weren’t allowed to use.The administration’s reasons varied: data said students wanted to be back, or we had lost online accreditation, or we have low online pass rates. It meant that already stretched students fought back tears as I explained how to apply to another college so they could finish the degree we had taken away from them. Students wrote petitions that were ignored. Thus, we all filed in every day. The peace officers who took our temperature at the gate were armed. Fear of gun violence competed with fear of Covid.

This kind of management intransigence is the norm, as is administrators' uncaring attitude towards staff. Some colleagues were accused of job abandonment for missing paperwork, two office hours, or cancelling a class before Thanksgiving break. Several have now quit tenured positions. Five of my tenured African American colleagues have left, as has an entire discipline. One department was retrenched.

Previous administrations viewed faculty as serious professionals. Now, online forms are hidden to monitor who asks for them; troublemakers do not go unnoticed. Now, room change requests must go through human resources, who will not miss a chance to be mean. One colleague with post-traumatic stress disorder was treated as hysterical because she requested one of the many empty classrooms with a window. Every day brings belittling messages explaining why we won’t help ESOL students, or staff the tutoring centre, or provide deaf faculty with sufficient interpreters.

Meanwhile, egregious areas of failure are left unattended. Take the situation with our library, supposedly the “heart” of our institution. It’s impossible to find a link to it on our college website. I’ve told the right people, filed website update requests, written letters; it seems that the difficulty is by design.

A tenured, newly minted PhD in library science should be directing the library, but she was kicked down in favour of someone with an MA in mathematics. He’s a white guy. She’s black. Even the outside evaluator paid to assess the situation thought this was odd. Unsurprisingly, the PhD quit, as did a second trained librarian. The mathematician is still running the library.

Despite it all, students do succeed, and they regularly take a moment to share their stories. Today, a young woman approached me at the chemist. I had submitted an essay she wrote to a local contest. Her eyes gleamed as she remembered the applause as she collected the award. Her course, the one I was hired to teach specifically, quietly disappeared from our offerings this year.

But despite these rare moments of affirmation, I am glad to be on leave. It was my psychologist’s suggestion. Initially, I went to my GP for a higher dosage of dubious antidepressants. Instead of prescribing them, he said, “I don’t mean to be condescending, but try to be positive. Find a therapist.”

I did. He can help in some ways, but is utterly useless in other very important ways. Neither he nor I can fix the library, policy upheavals, beleaguered colleagues, a foolish administration, moral injustice, declining enrolment, or needy students. So now I am just doing what therapists often suggest: I am writing about my trauma.

The author, who wished to remain anonymous, is a community college professor in a large city on America’s east coast.

- If you’re having suicidal thoughts or feel you need to talk to someone, a free helpline is available around the clock in the UK on 116123, or you can email jo@samaritans.org. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international suicide helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login