Spring semester is upon us. It is a busy semester, in which I will teach three courses – two old and one new – so, naturally, I am already busy preparing for it. Busy, that is, staring at a blank screen.

I have a particular kind of writer’s block, one that perhaps other academics have confronted. It has nothing to do with the crafting of lectures or drafting of exams, and everything to do with, of all things, course syllabi.

On my list of professional duties, writing a syllabus has always ranked highly on the dreary list, somewhere between serving on committees and attending convocations. The reasons, I suspect, have as much to do with the way we use syllabi as with the way we ought to use them.

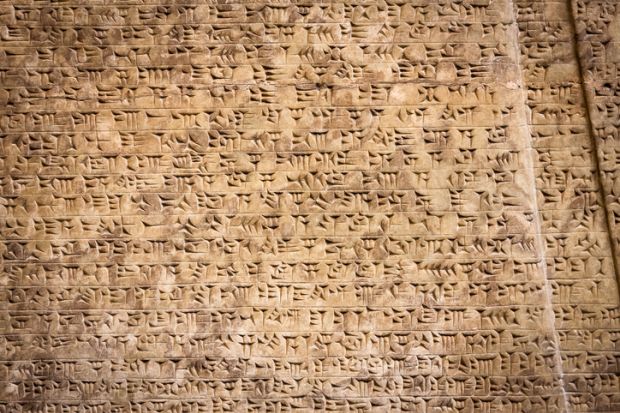

How did the syllabus ever become a thing at universities in the first place? Its beginnings were less than promising: the word is based on a misreading of the Greek sittybos, the parchment label announcing the title and contents of a text. But, beyond that, I’ve been able to find out little. Much has been written about the curricula of medieval universities, largely focusing on the famous trivium and quadrivium. But was there more than one way to teach these seven liberal arts? It’s hard to say, as the syllabus is rarely even mentioned in footnotes – another deeply embedded, unquestioned academic device that, nevertheless, was deemed worthy of their own ravishing history by Anthony Grafton in 1997.

Academics appear no keener to explain this particular fact of life to their graduate students than fathers are to explain those other facts of life to their sons. Think of the syllabus as the academic equivalent of a package of condoms: something we were given and whose mode d’emploi is taken to be self-evident but is anything but.

They share a transactional nature, too. Indeed, when academics write about the purpose of the syllabus, they mostly cast it in contractual terms. By the 1970s, notes the education specialist Susan Fink in a 2012 paper, the syllabus had become an “implied contract” between professors and students. “The syllabus sets forth the course requirements for the class and what is expected of students to earn certain grades.” Yet, as she drily concludes, this understanding of the syllabus “does not necessarily benefit the student or the instructor”.

Few questions make me bristle more than when a student asks: “What do I need to do to get an A in this course?” Most academics in the humanities still believe – or at least pretend to believe – that the goal of higher education is to know oneself, not to promote oneself. But is this, in fact, the real purpose of the syllabus? Or, at least, is it my real purpose when I write a syllabus?

In a sense, writing a syllabus is not all that different from making new year’s resolutions. It is a list of things I plan to do with students and a list of things I believe are good for them. But, as with my resolutions, those good things will be mostly ignored or forgotten in short order. And the syllabi, like the resolutions, tend to repeat themselves; writing them amounts to a scholastic Groundhog Day: the same script, with the same books and same aims.

This year my resistance to writing syllabi is even greater, though. The pandemic is partly responsible, of course, as is the breakdown in civil public discourse roiling my nation and so many others. Particularly in the US, we seem mired in a horror-tinged political Groundhog Day. All the more reason, I believe, that syllabi cannot simply repeat themselves.

On the one hand, there is something to be said about the perennial relevance of the Classics, especially in dark times. On the other hand, it cannot be gainsaid that the Classics risk appearing terribly irrelevant in an age when the very notion of perennial, at least applied to our political and physical climates, seems increasingly quaint.

What if we saw the syllabus not as a script or contract but instead as a wager? Or, rather, two wagers. The first is whether the students will even read the syllabus at all: see the recent news stories about Kenyon Wilson, a professor of music at the University of Tennessee, who planted in his syllabus easy-to-follow directions on how to claim a $50 cash prize – but none of his more than 70 students did.

The second wager is even greater. Rather than setting down what books will be taught and when they will be taught, the syllabus could say: “Here is why, now more than ever, I think these books should be taught. I will do my best to make their case and you will do your best to decide whether I succeed.” Perhaps it is only by ditching the script and recasting an agreement as an adventure that professors can respond to the urgency of our times.

It would remain for the students to accept the wager. Or, for that matter, to read it.

Robert Zaretsky teaches at the Honors College, University of Houston. His new book, Victories Never Last: Reading and Caregiving in a Time of Plague, will be published in April.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login