My professional resolution is to read less economics – and more novels. In these tumultuous and unpredictable times, what’s going on here and now seems all-consuming, and escaping to a novel might seem frivolous. But novels help to fill a gaping hole in economics, capturing the reality of human behaviour, going beyond aspects of life that are quantifiable and easily captured in simple mathematical models, and exploring the interplay between individual and society. If I could write a novel myself, I would. Sadly (perhaps unsurprisingly for an economist), I lack the emotional wisdom it requires, so must instead learn from others.

My personal resolution is to regain my love of nature. As a child, I loved wildlife. I had a poster of a squirrel on my bedroom wall and absolutely adored birds and butterflies. But, as economic recession set in, it became a constant battle merely to survive. It was easy to lose touch with nature.

Victoria Bateman, director of studies, fellow and Iain Macpherson lecturer in economics, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

I shouldn’t complain, but there is just so much to read about higher education these days. Maybe I am my own worst enemy, as I like to try to cover everything that comes into the office. I am beginning to creak under the weight of all that’s out there – and that is before I even get to reading for pleasure. My university-related resolution is to devise a really good filter so that I can properly distinguish between the signal and the noise. Tips on how best to do that would be gratefully received.

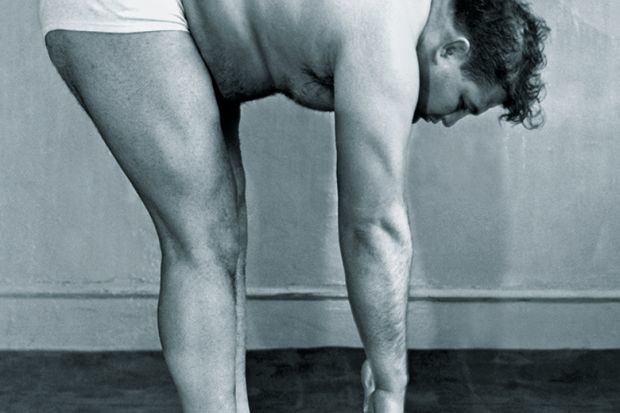

On the personal front, I have a mildly obsessive target to keep my weight at 13 stone. For someone who is 6’3’’ tall, an extra few pounds shouldn’t make much of a difference. But keeping an “ideal weight” in mind has guided my fitness and diet regime for nearly 30 years. My second resolution, therefore, is to continue to run along the seafront – hands up if you didn’t know that Sunderland is a city by the sea – across the seasons and in all weathers.

Sir David Bell, vice-chancellor and chief executive, University of Sunderland

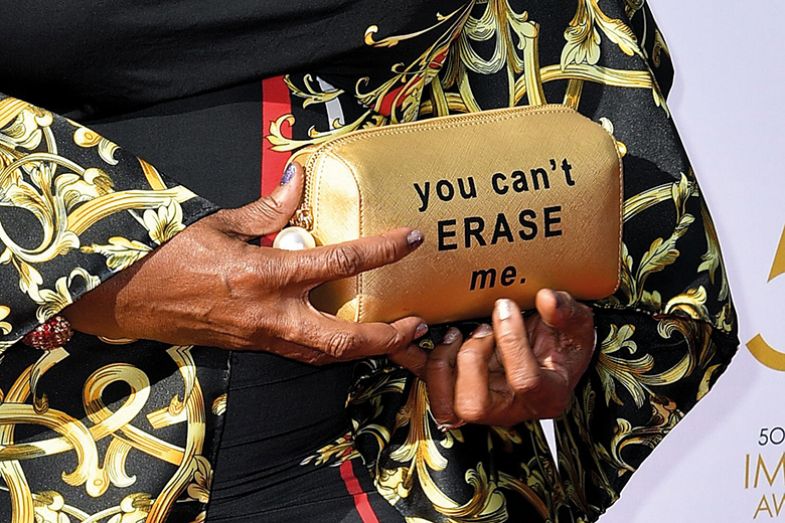

My main new year’s resolution is to keep talking and “banging on” about why racist practices continue in the so-called liberal academy. I will encourage colleagues working in universities and the wider higher education sector to acknowledge the presence of institutional racism and white privilege in their organisations and to address the very obvious inequalities that permeate all aspects of university life. I will keep saying the unsayable because, by remaining silent, we become complicit in perpetuating racism.

On a personal note, in 2020, I want to spend more of my hard-earned cash on life’s little luxuries: perfume, shoes and handbags spring readily to mind.

Kalwant Bhopal, professorial research fellow/professor of education and social justice, University of Birmingham

Resolutions come not singly, or in any particular order. These are all the things I resolve to cease doing – or never to do in the first place:

- Check the birth date in obituaries.

- Believe the agendas of meetings.

- Submit myself to appraisal or workload management.

- Fill in questionnaires on how to devise questionnaires.

- Complete compulsory online modules on how to talk to people without causing offence.

- Chair an interview panel.

- Suck eggs.

- Email people in the next office.

- Add smiley faces or turd emojis, as if a degree in literature was to be traded in for teenage grunts.

- Write references for those of whom I have no memory or who, if I have, I suspect ended up incarcerated.

- Use acronyms understood by no one outside or inside the university.

- Sponsor people who want to swim the Hellespont, English Channel or local drainage ditch on behalf of the incontinent.

- Write job descriptions so long that nobody in their right mind would wish to do the job.

- Refer to students as customers and the university as plc.

- Indulge the temptation to propose honorary degrees to the already dead, or likely to be so by graduation.

- Name any pop group from the last 30 years.

- Join LinkedIn unless I discover the closely guarded secret of how to leave it.

Christopher Bigsby, director of the Arthur Miller Institute and professor of American studies at the University of East Anglia

As a first-generation student myself, I have resolved to help first-generation students at my university (who make up over 40 per cent of the total number). My college began a programme this year to focus on and assist these students, who are very vulnerable to dropping out within a year or two. I’ve signed up to mentor a group of such students. I’m also rethinking my office hours and their function, as well as figuring out ways to locate first-gen students and give them the skills they need to succeed at university.

On a personal level, I’m going to try to disregard negative reactions to me and the book project I’m working on. I have a tendency to be too sensitive to criticism and often find myself stopping work on a project in response. A recent lunch with an editor turned into a bash-my-book-idea festival that left me with indigestion and indignation. Instead, I’m going to focus on why people are reacting this way and shape the book to consider/refute their positions. If I’m getting strong reactions, I must be on to something strong.

Lennard Davis, distinguished professor of English, professor of disability and human development and professor of medical education at the University of Illinois at Chicago

My personal and professional new year’s resolution is the same every year – but this time it’s for real! – and it’s about time management. There are unique challenges to our work. As my colleague Barb Voss once put it, academics are expected to run our own little corporations, holding all the roles: finance, accounting, fundraising, networking and publicity, as well as research and writing. How does one choose between a series of competing demands? Should I try to get reimbursed for that trip to Newcastle? Perfect the wording of a forthcoming essay that is already “good enough”? Peer-review a colleague’s article? Write a reference letter? Often, my approach has been based on the burning house model, whereby I prioritise what is most urgent, which means that by the end of term the houses are mostly still standing, but my broader projects have yet to be tackled. I surrender and accept that I am powerless in the face of such competing demands, so I resolve to gain skills to manage projects, attention and tasks.

Lochlann Jain, professor of social medicine at King’s College London and a professor in the department of anthropology at Stanford University

Next year, I will be abandoning my resistance to using social media to communicate with research students. Since I am blessed with the most creative and globe-trotting PhD students, their regular international travel and the odd potentially dangerous situation have led to slippage into WhatsApp, Twitter and Facebook. This has advantages. I know, for example, how late into the early hours one genius is working when I get an amazing YouTube clip showing me his latest find. I can instantly get reassurance that one of my intrepid young researchers is not caught up in the riot I’ve just seen on CNN. PhD supervision is being criticised in some quarters for its absence. But not on my watch, phone or tablet.

My personal new year’s resolution is the flip side of this: to find ways to control the above use of social media. I admonish my teenage hoodied niece and nephew for their phone use, but I am also gripped by middle-aged smartphone addiction. So in future I will wrap my phone in a tea towel, place it in a biscuit tin and hide it at the back of the sock drawer. This will give me at least 15 minutes of clear concentration. And I will divide my Twitter and Facebook accounts into work and personal. Following up a tweet about an LSE blog on contemporary slavery in central Africa with the result of one of my forays into what I call the Fluffy Web (perhaps a picture of a dachshund balancing a banana on its head) cannot be doing my reputation any good.

Joanna Lewis, LSE associate professor, Africa, London School of Economics

My professional goal for 2020 is to plan and initiate ways to make space for people of colour in the academy. “Making space” is a concept developed by Royona Mitra, a dance scholar at Brunel University London, and it refers to anti-racist practices of decolonising curricula and bringing in the voices and experiences of others that urgently need to be embraced and fostered by white colleagues in leadership roles. I know that such initiatives have to be developed with sensitivity to meet specific local and contextual challenges, as well as carefully monitored, so they don’t become smug “tick box” exercises. I know that they have to involve scholars (and potential scholars) of colour in their design without placing additional burdens on them. And I know they will also require me consciously to give up space myself, however vulnerable this may make me feel. In fact, I suspect it’s only when I feel that vulnerability that I will know I’m on the right track.

My personal resolutions are rather more straightforward but probably equally ambitious: to exercise more and to eat less bread.

Roberta Mock, professor of performance studies and director of the doctoral college, University of Plymouth

In 2020, I am committed to turning more explicitly to face the urgency of our times: the challenge of how, under the spectre of interlinked ecological, social and political forms of fracture, we are to live together in our common home. As a historian, that means talking explicitly about the contingency of all systems of power and the possibility for change. More broadly (and personally), it means more active membership of political and community groups and a more deliberate attention to spending time in nature and with people, ideally with a large glass of wine and a peal of laughter.

Tamson Pietsch, senior lecturer in social and political sciences and director of the Australian Centre for Public History, University of Technology Sydney, Australia

When I went through a similar exercise a few years ago, I resolved to finish two books. To my surprise, I have accomplished this: Sex in the Archives was published early this year (a New Year gift!) and Trans America is in press. Writing seems to come easier as one (how should I put this?) matures. Research, the lure of the archive, never loses its appeal. Since I am retiring in January, my main resolution now is to negotiate that change without too much trauma for my family. My having time on my hands is not something that any of us have really experienced. The danger might be too much Barry. Time with the granddaughters and a house in Greece may ease this time of transition.

My non-academic resolution is to attempt to stop watching my beloved Arsenal from behind the sofa. Sadly, that situation has not improved: Arsenal have not eased my pain. And I will now have more time to spend behind that sofa.

Barry Reay, Keith Sinclair chair in history, University of Auckland, New Zealand

In the world of science, interactions with external partners can be the best part of the job. But sometimes the fit just isn’t right, and it can take real courage to accept this, let alone do something about it. A wise colleague told me recently that, after years of bashing her head against the wall, she now works only on projects that make her happy and with people who make her laugh. I will be taking a leaf out of her book for 2020.

As my day job grows increasingly hectic and fraught, it has started to nibble away at more and more of my evenings and weekends. But I have a delightful husband and six-year-old son at home, and other interests that I’ve been neglecting, such as music making, dancing and spending time with friends. And please don’t even mention the fourth “lab lit” novel-in-progress, which has been languishing at the start of chapter two for a few years now and is starting to give me that accusing look. So in 2020 I will be carving out more time for my family and the rest of my real life – because this will actually make me more effective at work.

Jennifer Rohn, principal research fellow, and head of the Centre for Urological Biology, and Chronic Urinary Tract Infection Group, UCL

This year, I really want to focus on institution-building. That springs in part from my new job leading an institute (the Henry Luce III Center for the Arts and Religion) but also the unique environment of a seminary. Being a Jew – and one who grapples with faith at that – I’m surprised at how well it suits me living in an intentional Christian community, and training students for ministry and mission. With so many institutions and belief structures disintegrating at the moment, it feels quaint to say, but it’s refreshing to be around people who believe that their institution, however small, is doing something important and unimpeachably good.

I also want to stop eating chicken. Over the past several years, I’ve given up beef, then pork products, and now I’m waging a battle with poultry and its sundry enticements! Three factors finally tipped me over the edge. I used to gleefully enjoy the iconoclasm of eating bacon and playing fast and loose with the milk and meat kosher imperative, but as I get older I’m surprised to find myself getting a bit more traditional. Environmentally, I think eating meat is no longer sustainable. And finally – most boringly – I have high cholesterol. Farewell, chicken club sandwiches!

Aaron Rosen, professor of religion and visual culture and director of the Henry Luce III Center for the Arts and Religion, Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington, DC

In the quest for professional self-improvement, I almost threw off the shackles of my technophobia and bought a smartphone. I resisted when I saw the price of them (resolution: be less of a miser). I’ll stick with my dumb phone for another year at least. I’ve only just learned how to use PowerPoint. Apparently I am already out of date. I’d resolve to learn how to use “Interwapp”, “What’s Up, Doc?” and the evil Twitter, but life is too short and I’ll only confuse myself. Resolution: stick to paper handouts and maintain old-fogey persona. There are plenty of young colleagues in the department who can wow the students with techno.

As for extramural resolutions, where to begin? The usual suspects: less booze (unlikely), more dry nights (currently two a week and that’s a massive struggle), take up running (boring and short-lived), improve my Italian (not much there to build on in the first place), learn the piano (don’t be silly), quit chocolate (never eaten it, anyway), investigate long-term investments with a view to early retirement (now you’re talking).

Peter J. Smith, reader in Renaissance literature, Nottingham Trent University

My work resolution for 2020 is straightforward: read more books. I would add “slowly”. This is a paradox, in that I am suggesting doing more of something and taking longer over it, but if it can be done it will improve my working life immeasurably. I became an academic to read, first and foremost, and now (like everyone else) I mainly read in snatches, at high speed, and in a state of distraction – which is hardly reading at all. I also like to think people read my books, which is unfair if I’m not reading theirs.

My personal resolution is to stop rushing about so much. This is also pretty straightforward, but more challenging. I like rushing about and am generally no happier than in an airport departure lounge about to go somewhere far away. But I racked up tens of thousands of miles of long-haul flights last year, and drove nearly 30,000 miles, which, putting aside any arguments about the environment, is just an absurd amount of travelling in a single year. But I can’t imagine not doing it at all. Hence the qualification “so much”.

Richard J. Williams, professor of contemporary visual cultures, University of Edinburgh

As we age, we generally become far more conservative in our thinking, often through painful experience. We also become more entrenched in our ideas, turning scepticism into cynicism. It’s too easy – especially when reviewing grant applications and manuscripts with low success rates – to pick out the flaws. So I resolve to increase my level of trust, to restore some essential intellectual naivety, to allow more buds to blossom and to give fewer passes to safe science.

Non-academically but relatedly, I resolve to learn more from my grandchildren, from the sheer originality of their efforts to make sense of an amazing and ridiculous world. Staying youthful in mind doesn’t need blood transfusions from young people, as practised by some modern tech-billionaires/vampires, it just needs their perspectives on life. In childhood, we are all explorers. Some of us are lucky enough to remain in that stage and somehow to get paid for it. But retention of naivety is both hard and takes ever more effort.

Jim Woodgett, director of research/senior investigator, Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, and professor of medical biophysics, University of Toronto

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: New year, new me

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login