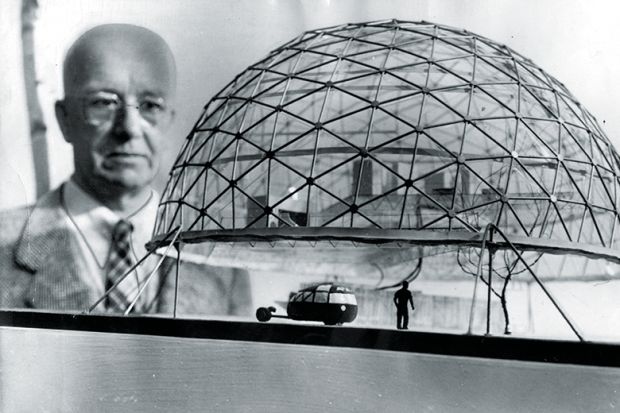

Paul Dirac, the founder of relativistic quantum mechanics, was known as “the strangest man”, famous for his long silences and quirky behaviours such as relaxing by climbing trees in a suit. The outstanding architect and designer Buckminster Fuller didn’t agree with the words “down” and “up”, proposing instead the use of “in” and “out” to refer to the centre of the gravitational field of the earth. Pythagoras forbade himself as well as his followers (and a bull) from eating beans. According to legend, he died while being hunted down by a band of attackers and refusing to hide in a bean field. These anecdotes may seem quaint, and perhaps irrelevant, but quirkiness is not a glitch. It’s a feature. And we’re losing it.

While the majority of scientists and innovators have decidedly “normal” dispositions, there is no doubt that extremes abound at the forefront of discovery. Thomas Kuhn, the late and great philosopher of science, distinguishes “normal science” from paradigm-shifting extraordinary science in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

Characterised by the more or less linear extension of existing knowledge, “normal science” can be undertaken by the majority of scientists, the need for extensive labour and creativity notwithstanding. Conceptual shifts, however, require a departure from normality, a willingness to attract opprobrium for unconventionality from one’s peers, not merely thinking outside the box but living outside it. To build a meadow, we need the grass (the majority), but without the honeybees (the rare specimens) flitting about, connecting and pollinating plants, the meadow would wither. If we combine both, the blooming plants bask the meadow in natural splendour.

Drawing on the founding editor of Wired magazine Kevin Kelly’s notion of inevitability, the invention of electricity was a piece of century-defining genius. However, the electrification of appliances from looms to washing machines, as impactful and important as they may be, was not. Incrementalism is what made us progress so steadily over the past decades and centuries, and requires hard work and intelligence. Yet the formula “take X and electrify it” didn’t require breaking with convention as much as the groundbreaking invention of electricity itself did. Here’s where we need trailblazers, nonconformists and innovators. Here’s where we need honeybees – and we’re not getting them.

As a society, we tout the values of interdisciplinarity, of “breaking down the silos”. We infuse our youth with rousing commencement speeches and proclaim our noble intentions in mission statements. Yet in practice we refrain from these nonconformist ambitions. When applying for jobs or research grants your chances are maximised if you’re already experienced in the topic you’re applying for and if your ideas and ambitions exhibit incrementalism. Your chances are worst if you come from a different background and aim to do something revolutionary.

If we really embrace interdisciplinarity and radical innovation, why do we punish those who aim to do so? Two issues come into play under the current set-up. One is that we select those applicants that conform and let potential innovators fall through the cracks. The other is that even those applicants who initially intended to walk their own path are transformed by the system, adapting to the torrent of discouragement delivered at every attempt to dissent.

Take the system of academic tenure for university professors. Designed to enable academic freedom by protecting professors from censorship and societal restrictions, it slays what it intends to create. Applying for research grants and scientific positions for 10 years prior to tenure, researchers are subjugated to conformity and adherence to existing paradigms. And yet, incredulously, we believe – we expect – researchers to somehow miraculously dispose of the decade-old mantle of conformity the instant they are endowed with tenure and transform into rebels with a cause.

So how is it that we still manage to have unconventional and radically innovative characters, in science and business alike? By and large, it’s not because of but rather despite our sanctimonious systems. The chance meeting with a connection might provide a honeybee with the right job, initiating its career. A powerful mentor might extend support and protection to the honeybee, thereby enabling it to flourish. But at what cost? How many Einsteins, Curies or Diracs did we lose as they fell through the cracks of our standards and expectations?

There are ways to open back doors for exceptions without hurting or disadvantaging the majority.

ETH Zurich in Switzerland, my own institution, has an approach to admissions that may shine a light on potential options for this endeavour. Not only can every Swiss citizen holding a high school degree enter undergraduate studies at ETH Zurich, but people with no formal schooling also have a shot at entering its halls. By offering an entrance exam as an alternative, ETH Zurich opens its doors to anyone able to successfully engage in undergraduate studies, irrespective of formal requirements. Prestigious scholarships, such as the German Academic Scholarship Foundation, which are normally accessible only to students with nominations from esteemed connections or mentors (both conditional on social agreeableness and, to some extent, conformity), have begun to offer tests for initiative applications. Creating a back door can be done without affecting the traditional and expected entrance gates.

This is “breaking down silos”. Instead of requiring a list of potentially meaningless milestones, we should demand what we proclaim to want: originality and revolutionary thought and vision. We should offer honeybees a way into the meadow through optional tests or competitions. This way, even though the majority can be treated the same as they are today, we will save more of the nonconformists from vanishing than we do now. Albert Einstein himself took the ETH Zurich entrance exam as he lacked the required degree to study there. Imagine if that one fell through the cracks because we insisted on a linear and conventional path forward.

Daniel Bojar is a PhD student at ETH Zurich in the department of Biosystems Science and Engineering.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Quirkyness is endangered

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login