Working as the archivist at St George’s, University of London – one of the oldest healthcare and medical schools in the UK – has led me to discover a treasure trove of gruesome artefacts. Perfect timing for Halloween.

Among the artefacts I’ve discovered are a cloth used to wrap a dead king and records regarding a scandal that provoked Charles Dickens to condemn post-mortem practices as “shocking”.

The cloth (pictured below) is called a cerecloth – material treated with wax and used for wrapping dead bodies. It was used for wrapping the dead body of King George II in 1760.

The section of cloth was cut by Caesar Hawkins, surgeon to St George’s Hospital from 1735-1774 and sergeant-surgeon to both King George II and King George III.

These artefacts have come to light as I’ve been busy discovering the rich history of the medical school connected to St George’s Hospital. The hospital was founded in 1733 at Hyde Park Corner, with the medical school being formally established 98 years later in 1831.

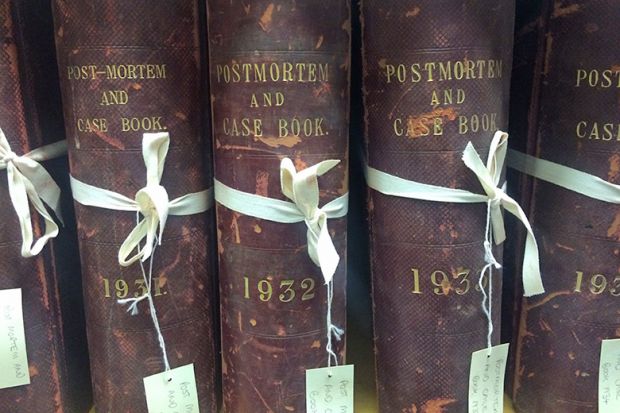

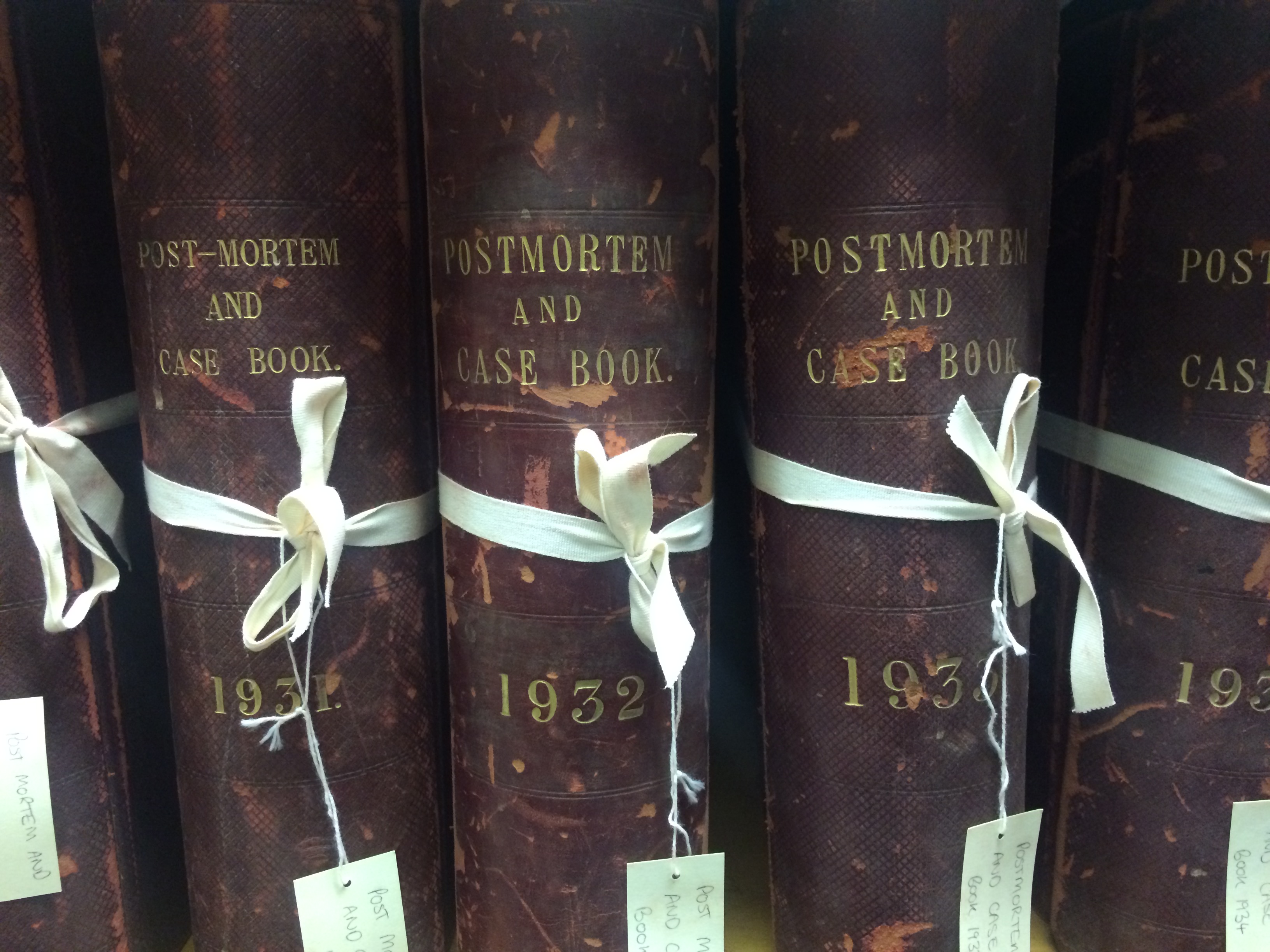

A vast number of post-mortem case books (pictured) from the 19th and 20th centuries are held in the archive, providing detailed pathological findings from the examinations of corpses. These findings have often revealed the tragic consequences of ill-informed medical treatments – such as the fatal ingesting of mercury, turpentine and tar.

One post mortem record relates to an incident known as "the hospital scandal" of the 1850s that resulted in novelist Charles Dickens writing a letter to the governors of St George's Hospital.

A letter from the famous author reveals that a widow named Margaret Purvis, from Devil's Acre in Westminster, died from cancer at the hospital. A post-mortem examination was carried out by Henry Gray – the renowned anatomist, surgeon and author of Gray’s Anatomy – in 1856 and, following this, a family-friend went to take care of Mrs Purvis' body.

She was shocked to find the body naked and dishevelled on the same slab as the corpses of two naked men.

Asked to help by a family friend, Dickens wrote a letter to the hospital governors in 1857 stating that the body’s "appearance...was so forlorn and shocking, that she [Mrs Bragg] hid it from the sight of the daughter of the deceased, until she had been able to perform those functions for it, which decency and humanity usually suggest".

Dickens’ letter resulted in the hospital creating a new room to store the dead temporarily. Nurses were employed to dress and decently dispose of the bodies in addition to looking after relatives of the deceased.

The archive houses an array of frightful surgical tools, including bone cutters for chopping off fingers or toes, and a trepanning tool for cutting holes in the skull. These fascinating objects illustrate the changes to surgical practices through the ages.

The bone cutters and trepanning tool are part of a set given to student Edward Walker as a "prize" for performing the best dissection during the 1856-1857 teaching year (pictured below). The set housing the tools also contained two mysteriously hidden compartments, concealing a bone saw and tourniquet.

Other items include many pictures from the history of the university including of the Kinnerton Street dissection room from 1860 when the medical school was located on Kinnerton Street in central London. It shows a cadaver on the table, a skull, and some anatomical drawings in the background. Pictured at the front centre-left is renowned anatomist and surgeon Henry Gray.

Henry Gray played a significant role in the history of St George’s. He studied at the medical school, and his great ambition was to become head surgeon of the hospital. Gray began showing symptoms of fever shortly after being nominated as assistant surgeon, which progressed to confluent smallpox. He died tragically within one week.

Carly Manson is a university archivist at St George's, University of London. For further information about the history of the post-mortem, and the post-mortem records of St George’s Hospital, see this blog. All photographs used above are copyright St George's, University of London.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login