Some Antipodean universities face an existential threat from the loss of Indian students, as Covid-induced border closures exacerbate Australia’s plunging stocks in the subcontinent.

While students from China supply critical income for Australia’s research-intensive institutions, many other universities rely more on India. But as with China, flows from India peaked before the pandemic.

And unlike Chinese students, who were discouraged from coming to Australia amid escalating bilateral tensions, Indian students were lured elsewhere by mounting competition – particularly from the UK, which announced the reinstatement of post-study work rights in September 2019.

Coronavirus has given them another reason to choose the UK, which has kept its borders open during the pandemic. Unlike their peers in China, where Covid is under control, students in India are in a Covid hot spot and less averse to travel.

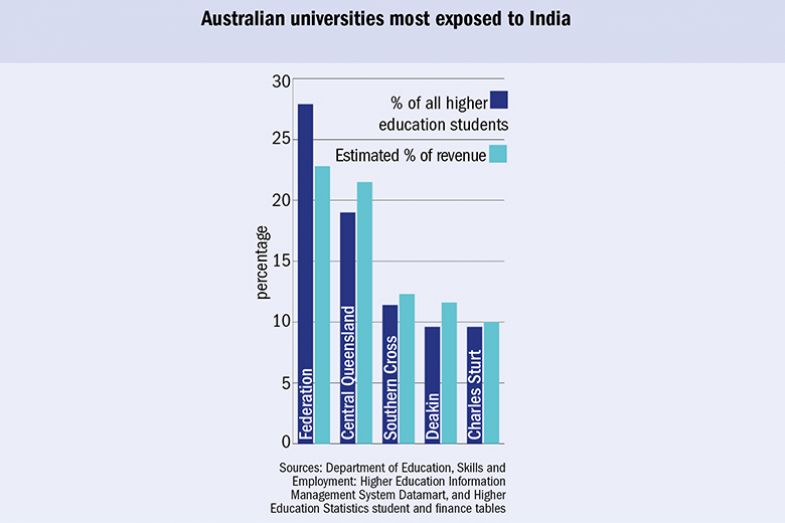

Australia’s India-dependent universities are more financially challenged than the cashed-up institutions that raked in Chinese tuition fees. A dozen Australian universities obtained more than 5 per cent of their institutional revenue from Indian students in 2019 – the last year for which financial accounts are widely available – with exposure exceeding 10 per cent at five universities and 20 per cent at two.

All but one of the 12 would have seen their 2019 surpluses reversed without revenue from Indian students, with four in deficit by more than A$50 million (£28 million). The two most exposed institutions were Federation University Australia and Central Queensland University, which has posted a substantial 2020 deficit.

Australia’s higher education enrolments from India fell by 12 per cent last year, with commencements almost halving. “We are keeping a close eye on these figures,” education minister Alan Tudge acknowledged in March.

These problems predate Covid. Student visa grants to applicants in India crashed by around one-third over the seven months between the announcement of the UK work rights and Australia’s suspension of visa processing.

The new UK arrangements offer two years’ work rights on completion of a master’s degree, which typically lasts for one year – unlike Australia’s two years.

Phil Honeywood, chief executive of the International Education Association of Australia, said this made it difficult for Australian universities to compete, and necessitated “a serious conversation with the federal government about policy changes that will provide more accommodating student visa settings”.

Rupesh Patel, general secretary of the Association of Australian Education Representatives in India, said the UK was the only country that had increased student recruitment from India during 2020. Canada also posed a major competitive threat, while the US was sending “positive signals” under Joe Biden. “Australia will have to offer more benefits to international students…to compete,” Mr Patel blogged.

India edged out China last year as Australia’s top student source market in terms of visa applications. By the year’s end, there were more than 91,000 Indian student visa holders in Australia compared with 74,000 Chinese, with immigration officials processing more than twice as many applications from Indian as from Chinese students.

But 85 per cent of these applications came from Indians who were already in Australia and hoping to start new courses.

Angela Lehmann, head of research with The Lygon Group consultancy, said Australia’s failure to attract more fresh students from the subcontinent undermined the “enormous potential” of the educational relationship with India. “Everyone keeps worrying about China, but India’s probably more concerning in terms of a long-term loss of market share.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login