Efforts to widen participation in higher education vary greatly in different parts of the world: an ethnic minority in one country could be a majority group in another, for example, while even collecting national-level data on these sorts of characteristics can be nigh on impossible in parts of the developing world.

But is there value in sharing global best practice in an area that is so rooted in local circumstances? And is it even possible to compare countries’ performance on equity of access to degree courses?

A new analysis of widening participation policies in 71 countries across six continents makes the case that both are possible – and worthwhile.

The review, authored by tertiary education expert Jamil Salmi, finds that while most of the nations considered had made equity a policy priority, too many paid only “lip service” to the issue, failing to back up this commitment with meaningful interventions.

To find out which countries are addressing access challenges most effectively, the report rates countries in one of four categories. Of the 71 systems considered, only six – England, Scotland, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand and Cuba – are labelled “advanced”, meaning that they have formulated and implemented a comprehensive equity strategy.

A larger group of 23 countries – including the US, Spain, Wales, France, Canada and Israel – fall into the “established” category, which means that they have formulated an access strategy and are putting in place policies to implement it. The largest group – made up of 33 countries including Argentina, Japan, Morocco, Kenya, Indonesia and Russia – is labelled “developing”, meaning that these nations have put in place the foundations for an equity strategy but have not defined policies or put much investment in the area.

Only nine countries – including Egypt, Laos, Haiti, Nicaragua and Sierra Leone – are deemed “emerging”, meaning that they have formulated broad goals but has done little in the way of concrete interventions.

According to Dr Salmi these latter countries are inessence fragile states – ones recovering from conflict, political instability or natural disasters – and, despite having started thinking about improving access to higher education, they have yet to translate this into resources.

Dr Salmi noted that the advanced group is largely made up of wealthy Commonwealth countries that have mature and developed higher education systems. As a result they can give more attention – and funding – to the obstacles faced by students from under-represented groups. The outlier in this group is Cuba, the only socialist country that has consistently put a great emphasis on access since the 1959 revolution, according to Dr Salmi.

Consistency in their strategies, goals and targets for widening participation is what they all have in common, said Dr Salmi. “There are other countries, particularly in Latin America, where the frequent changes in government and technical teams have resulted in a lack of continuity, which makes enacting change very difficult,” he told Times Higher Education.

Some richer countries such as the US and Canada, which have developed and well-respected higher education systems, failed to get top marks. Dr Salmi attributed this to their federal political systems, which mean that they have fewer comprehensive national policies. That in turn means that levels of access and success vary across the country. Australia, which is rated advanced but has a federal system, proves to be an exception to the rule by aligning its policies through its national education department.

The report also considers the types of groups that are targeted by equity policies: four out of five countries prioritise the needs of low-income and disabled students. Sixty per cent target gender groups (typically women) with their policies, while ethnic minorities are a priority for a similar proportion.

Other groups targeted include, for example, demobilised guerrilla fighters in Colombia, families with more than three children in Georgia and South Korea, and, in a number of cases, care leavers.

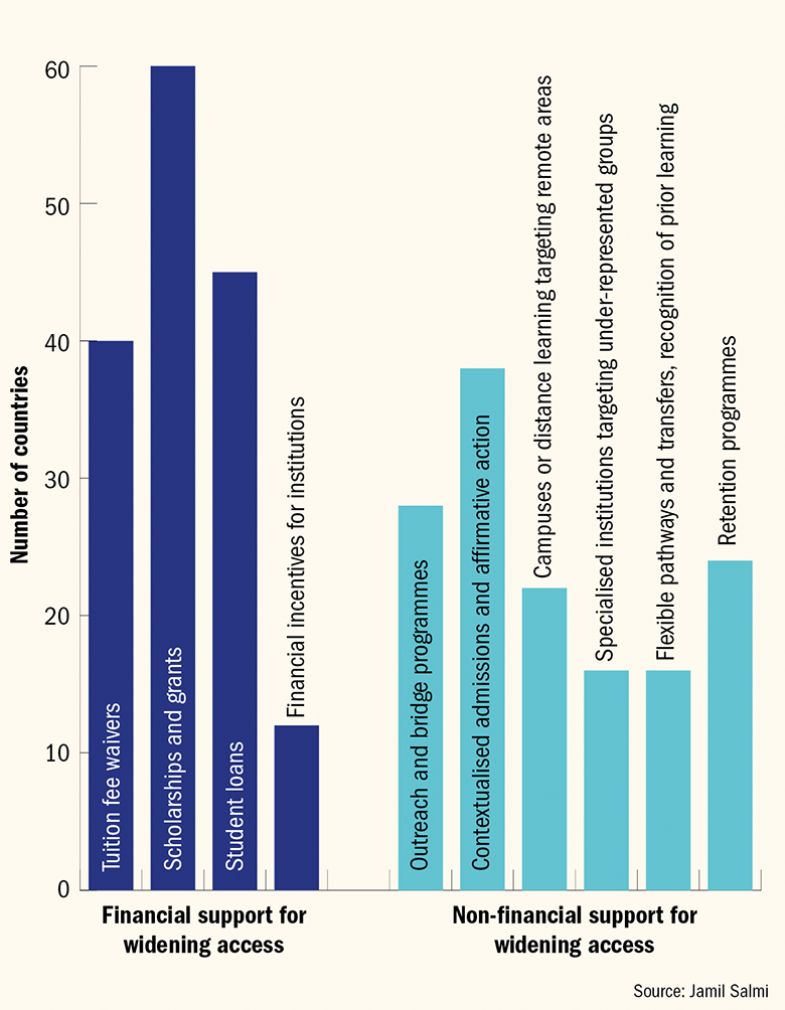

Dr Salmi considered how these groups are targeted. Only one in three countries has set specific access targets for named groups, but a wide variety of techniques are deployed to try to improve access. Many use financial measures, such as tuition fee exemptions, scholarships and student loans. A potential drawback is that these are often directed only at students in public universities and, in some sectors, private institutions play a key role in the sector.

Some systems give universities direct incentives by making some of their funding dependent on progression towards equity goals: in South Africa, for example, universities with a higher proportion of black students get additional resources.

Non-monetary support can be provided too – most frequently in the use of contextualised admissions, in which entry requirements are lowered for students from disadvantaged groups, but also through outreach and retention initiatives, or the creation of institutions specifically designed to serve remote areas or minority groups.

Investing in equity: support for widening access

How, then, can these data be used? With universities increasingly being compared with each other in international rankings, there is a temptation to call for equity measures to be included in such tables’ methodologies. Here, the challenge is collecting comparable data.

Pauline Rose, professor of international education at the University of Cambridge, said that it could be dangerous to say that one country has the most equitable access to higher education and another has the least without understanding why that is the case.

“You have to recognise that it is context-specific, and there is no blueprint. The specifics of a country’s labour market that graduates will be moving into need to be thought about, for example,” she said.

However, Professor Rose argued that universities and policymakers could look to other countries in search of best practice in widening access. There are general principles that apply across different circumstances, such as getting the foundations of a system right and tackling inequalities early on, she said, adding that “a country looking to improve can take that principle and adapt it”.

Graeme Atherton, director of the UK’s National Education Opportunities Network, supported the launch of the report for the first-ever World Access to Higher Education Day, and said that comparing countries around the world is important not only for sharing best practice but also to help with policy advocacy.

“While the context may differ, the fundamental challenges are still the same,” he said. “For example, during World Access to Higher Education Day, we heard from Brazil about working with ex-offenders and getting them into university – that’s something that’s also going on in the UK.”

Dr Atherton said that collecting more worldwide data and sharing it was incredibly important.

“Lots of academics work internationally, so why not do it in this area? We know that working together across different countries is hugely beneficial in other aspects of higher education, so logically it makes sense to do it when it comes to widening access,” he said.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Wider access: striding or lagging?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login