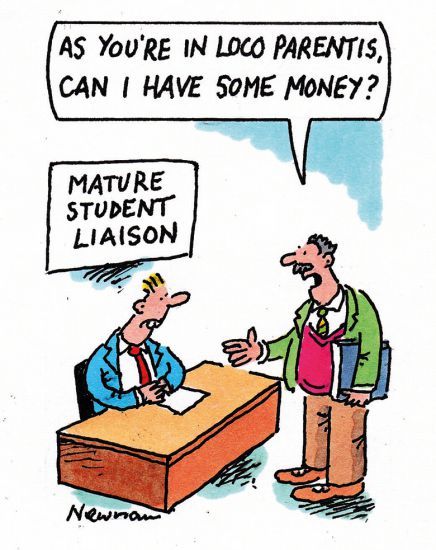

Sector leaders were summoned to London on 28 February for the launch of English higher education’s new regulator, the Office for Students, where Sam Gyimah, the universities minister, topped the bill. Eyebrows were raised when Mr Gyimah called on higher education institutions to act “in loco parentis” for their students, “offering all the support that they need to get the most from their time on campus”. Academics might question how much of their time they should be devoting to “parenting” people who are indisputably adults – and, given that a key benefit of university for many students is getting away from their parents, it’s questionable how much in loco parenting they want to receive. You can’t help but wonder whether, despite what the government says about turning around the collapse in mature study, its starting assumption is that students are 18-year-olds and leaving home for the first time.

Mr Gyimah was less keen to show his face at a meeting of the Commons science and technology committee on 6 March, which he had been asked to attend for questioning about research integrity. In a letter, published on 5 March, Mr Gyimah said that Sir Mark Walport, the chief executive of UK Research and Innovation – who was also scheduled to appear – was “better placed” to discuss research integrity and that “it would be a better use of the committee members’ time to focus questions on research integrity to UKRI, as opposed to myself as a government minister”. Norman Lamb, the committee’s chair, was decidedly unimpressed. “He tells us that the detail of how government-funded research is undertaken, and its standards and integrity, is not a matter for him,” said Mr Lamb, who added that Mr Gyimah’s “non-attendance risks the research community concluding that this important area is not a ministerial priority”.

An ongoing battle at a US university over whether to rescind an honorary degree held by Donald Trump has now pitched faculty against trustees. In a formal faculty vote, an overwhelming majority of academics at Lehigh University, in Pennsylvania, backed a motion to revoke the 1988 degree awarded to the US president “based on a long history of numerous documented statements that are antithetical to our core values”. However, local newspaper The Morning Call reported on 2 March that the university’s board of trustees had refused to heed the calls, issuing a statement that the institution should demonstrate “openness to and respect for the broad views and perspectives of our many university constituencies”. It is not the first time that trustees have refused to revoke the degree: they did the same last year in response to a petition from a former student.

UK universities have seen their fair share of disruption recently, as the walkout at 65 institutions over pension reforms enters its third week. Vice-chancellors will have no doubt been thrilled, then, to see snowfall bring further disruption to campuses last week, with Scottish universities in particular being forced to shut for several days. Other institutions seemed less inclined to be sympathetic towards staff, however. At the University of East Anglia, acting registrar and secretary Ian Callaghan wrote to employees to tell them that “if staff have been unable to get to work they can take annual leave or unpaid leave or discuss with their manager arrangements for making up the time lost”. While university managers might be confounded by pension reform, they seem determined not to be tripped up by the weather.

Government ministers in the UK are doubling down on the prime minister’s call for university to no longer be seen as the automatic choice for school-leavers. The Daily Mail reported on 5 March that skills minister Anne Milton had suggested that privately educated pupils with top A levels should consider a degree apprenticeship instead of an academic course at top institutions such as the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. “Intellectual snobbery should not get in the way,” she said. “You might feel that you’ve ticked a box with your child going off to university, but if they haven’t got a job at the end of it they’re going to be back home in three years’ time.” But good luck persuading parents who send their children to Eton that this applies to their offspring and not “other people’s children”. One look at the university destinations of Eton-educated ministers in the current government tells you all that you need to know about how unlikely this is to change the entrenched snobbery around class and university.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login