The UK economy could lose out on a potential £2 billion a year Brexit “depreciation dividend” from increased overseas student numbers if the Home Office pursues plans to restrict student entry, according to a major analysis.

A report by London Economics, published by the Higher Education Policy Institute and Kaplan International on 12 January, bills itself as the “first proper econometric analysis of the impact of Brexit and other global events on the demand for UK higher education”, basing its forecasts on historic data about how worldwide economic factors influence international student recruitment.

There is a potential benefit in increased overseas student fee revenue for UK universities from a depreciation in sterling prompted by the vote to leave the European Union and changes in the EU student fee regime likely to follow when the UK exits, but it would not be evenly distributed across universities, says the report.

The universities of Cambridge and Oxford could gain about £10 million a year in fee income, while some less prestigious institutions could lose about £100,000 a year through reduced EU student numbers, finds the report, written by Gavan Conlon, Rohit Ladher and Maike Halterbeck of London Economics.

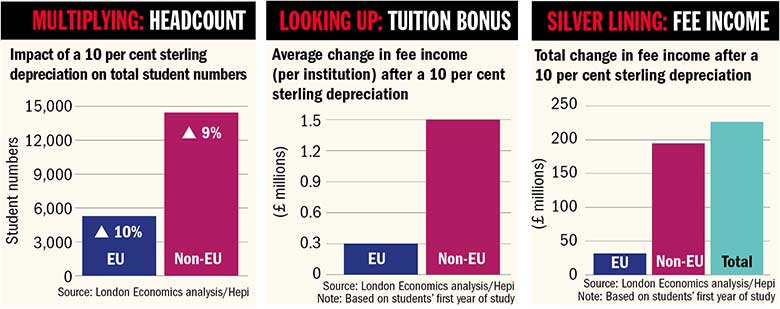

The analysis says that a 10 per cent depreciation in sterling – which Dr Conlon described as “realistic” in light of sterling’s path since the EU referendum – could bring in an extra 20,000 students and fee income of £227 million to UK universities by making them more attractive to overseas students.

There is also a student recruitment downside to Brexit. Raising EU student fees to the level currently charged to non-EU students and removing access to fee loans could reduce enrolment from EU nations by 30,000, or a 57 per cent decline, says the report.

But as EU students would be paying higher fees than at present, the net loss from changes for them would amount to only £40 million in the first year.

The combined effect of depreciation and EU fee and loan changes was found to be “potentially positive – amounting to £187 million in students’ first year of study – although there would be significant variation across institutions”, says the report.

But the positive impact from sterling’s depreciation “assumes that the resulting additional 20,000 students are permitted to study in the United Kingdom. If this is not the case, then the £227 million potential gain that might be achieved by UK higher education institutions may not be realised or only realised in part – thus representing the potential loss associated with restricting international student numbers”, the report says.

Taking into account the overseas students’ non-tuition fee spending and the impact on universities’ wider “supply chains”, the “estimate of potential loss” if these 20,000 extra students were not allowed into the country rises to about £2 billion a year, the report says.

The £2 billion figure on “indirect and induced effects” from overseas student spending is based on estimates in a 2014 report published by Universities UK.

Times Higher Education has reported that the Home Office has been modelling the impact of a major reduction in non-EU student enrolment allowed by UK universities.

The Conservative government’s drive to reduce net migration to the “tens of thousands” – and its refusal to remove students from the target – appears to make further restrictions on student visas inevitable.

Nick Hillman, Hepi’s director, says in his foreword that the analysis illustrates that the “hard facts mean any further crackdown on international students will not only damage our fantastic educational institutions but also the whole economy – and therefore the lives of those who voted Leave as well as those who voted Remain”.

The report’s authors say that they analysed the likely impacts of depreciation and fee rises by constructing a database including information on 189 countries, looking at UK and other nations’ overseas student numbers over a period covering more than a decade up to 2014-15, and judging the impact of factors such as variations in exchange rates, international gross domestic product (GDP) growth, as well as energy prices – a significant factor in student demand from major oil-producing nations.

Dr Conlon told THE: “If there’s a depreciation [in sterling], the result of this is that fees in the US appear more expensive.

“This has the effect of changing the decisions of individuals: instead of studying in the US, they’ll study in the UK.”

Dr Conlon added that it was a “basic principle of economics that UK goods will become more attractive following a depreciation”.

He continued: “What we’re saying is that there’s this money on the table and universities could, potentially, accrue this income – and additionally there’s indirect and induced impacts. And when you put it all together it’s in the region of £2 billion per annum.

“Potentially, there’s a very significant depreciation dividend to the higher education sector.”

Such additional income “might provide more financial security [for UK universities] and it might allow for otherwise marginal courses to continue to be run”, said Dr Conlon.

He added: “The economics is potentially positive in terms of the depreciation. But it has to be permitted politically.”

Alistair Jarvis, deputy chief executive of Universities UK, said that the analysis "provides a stark warning of the potential economic loss associated with policies that restrict European or international student numbers. Universities need the right support from government, through a combination of securing the best deal from the [EU] exit negotiations and immigration policy change, to play a central role in the UK’s future success, post-Brexit.”

Meanwhile, the analysis also suggests that the UK’s abolition of post-study work visas in 2012 – seen by many as a key factor in the dramatic fall in Indian student numbers in particular – “was associated with a 20.3 per cent decline in enrolment at undergraduate level”. But it was also “associated with a 7.2 per cent increase in enrolment at postgraduate level”, the analysis adds, although Dr Conlon said that the reasons for this were “open to interpretation”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login