Universities have been urged to improve training for PhD supervisors as new figures show that a third of doctoral students in Europe fail to complete their thesis within six years.

A survey of 311 institutions by the European University Association (EUA) reveals that, while the PhD completion rate across the continent is improving, 34 per cent of candidates still fail to finish their doctoral dissertation within six years – with many of these students expected to have dropped out altogether.

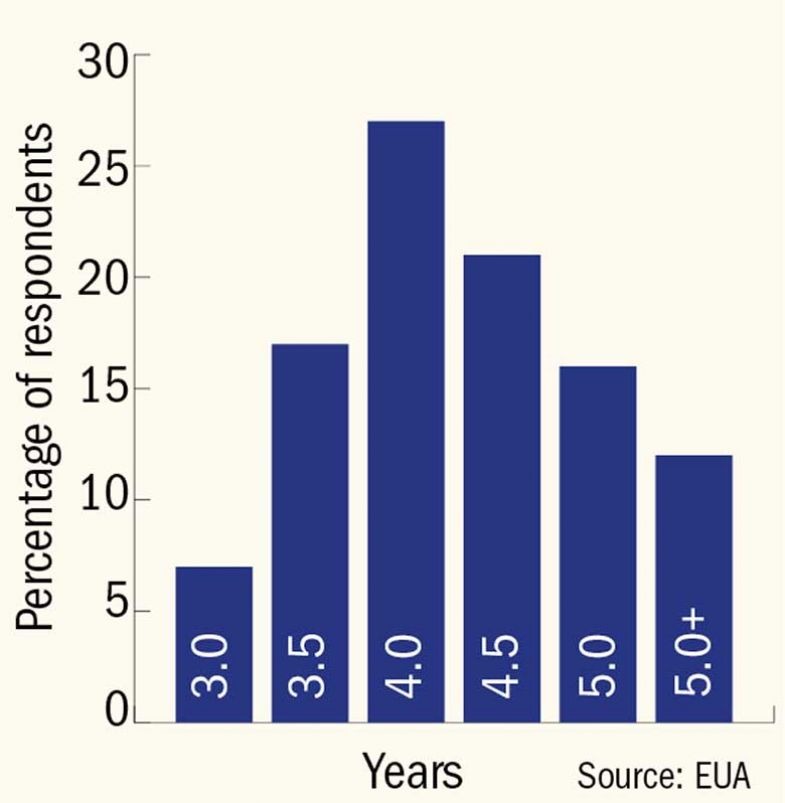

The EUA’s Salzburg Principles on doctoral education state that PhD programmes should “operate within an appropriate time duration”, approximately “three to four years full-time as a rule”, but only around half (51 per cent) of respondents said that doctoral students who did complete typically did so within this time period. More than a quarter said that the average completion time was five years or longer.

Alexander Hasgall, head of the EUA Council for Doctoral Education (CDE), said that “the risk that the thesis is not defended after six years” increases in cases where the average duration is longer than the recommended three to four years.

Almost half (49 per cent) of universities reported that the completion rate at their institution has remained stable compared with a decade ago, while 35 per cent reported an improvement, and 16 per cent a decrease.

Meanwhile, 43 per cent of universities indicated a decrease in the average time to completion compared with 10 years ago, while 15 per cent said that there had been an increase and 42 per cent said that it remained stable.

However, the report notes that there are significant differences in completion rates in different countries.

The study, Doctoral Education in Europe Today: Approaches and Institutional Structures, was published on 17 January by the EUA-CDE in collaboration with Ghent University’s Centre for Higher Education Governance. Its respondents, drawn from 32 European countries, represented 21 per cent of doctorate-awarding institutions and 40 per cent of doctoral candidates in the region.

The data show that just 12 per cent of universities provide mandatory training for PhD supervisors across all doctoral programmes, while only a third (33 per cent) of institutions dictate the maximum number of doctoral candidates per supervisor across all programmes. Voluntary training for supervisors in all doctoral programmes is provided by 36 per cent of universities surveyed.

Luke Georghiou, chair of the EUA-CDE steering committee and deputy vice-chancellor of the University of Manchester, said that the main factors leading to PhD students dropping out were low barriers for entry and insecure levels of funding.

He added that “structured doctoral education improves completion rates”.

“If the doctoral candidates are part of a cohort and are supported and well monitored throughout the pathway, they are more likely to be taken to completion,” Professor Georghiou said.

Average PhD duration

Dr Hasgall said that most doctoral studies begin with an “exploratory phase”, during which candidates can decide if they want to continue with the programme, which can also lead to some students dropping out early on.

Paolo Biscari, a member of the EUA-CDE steering committee and dean of the doctoral school at the Polytechnic University of Milan, said that previous research has shown that, in Italy, around 90 per cent of PhD candidates that aspire to a career in academia complete their thesis, and the main reason for students dropping out is that they receive a job offer during their studies.

“It is not that they failed their PhD but that [they] obtained what they were looking for,” he said.

However, Professor Biscari added that universities still have “a lot to do” to improve training for PhD supervisors. He said that some institutions have introduced mandatory training for new professors, which will improve the situation in the long term, but institutions could “try to speed up the process”.

“Candidates working with supervisors who have been trained show [fewer] problems and much more satisfaction than candidates working with general professors,” he said.

Alexandra Bitusikova, vice-rector for research at Matej Bel University in Slovakia and author of the 2017 book Structuring Doctoral Education, agreed that supervision was “still a big challenge” across Europe.

She said that in eastern European countries such as Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Poland, PhD supervisor training does not exist, and “in more advanced countries it is still not common”.

“Usually there is big resistance from the supervisors, who think they know everything,” she said, adding that “supervisors often cannot keep up with doctoral candidates but they do not want to lose power and respect”.

Meanwhile, in many less wealthy countries, doctoral students are “misused for all kinds of tasks for their supervisors”, which can result in them receiving heavy teaching loads, she said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login