An irate lecturer posted a lengthy online rant after his entire class failed to show up in the first week of term, the Evening Standard reported on 13 July. Adrian Raftery, associate professor at Australia’s Deakin University, hit out at his no-show students who “couldn’t be bothered to show their a*** up” as he uploaded a photo of his empty lecture room to LinkedIn, the Standard said. “I don't know about you but my generation always showed up for lectures and seminars, particularly at the start of semester,” said Dr Raftery, who asked fellow academics for tips on what to do “if they were in his shoes”. “Don't show up for the next class or go but play on your phone and see what the reaction is,” replied one LinkedIn user.

Princess Eugenie was initially rejected by Newcastle University as “not good enough” before it discovered the royal’s identity, an academic has claimed. The Queen’s granddaughter was turned down for a place to study English literature but was later offered a place on a less competitive combined honours course when “horrified” university authorities realised who had applied, said Martin Farr, a history lecturer at Newcastle, in a lecture to the anti-monarchist campaign group Republic. An Italian member of staff had “not noticed that Princess Eugenie of York from Sandringham may have had more significance for the institution than another applicant”, said Dr Farr, the Daily Mail reported on 16 July. A Newcastle spokesman said that it was not unusual for students without sufficient A-level grades to be offered a place on less-heavily subscribed courses.

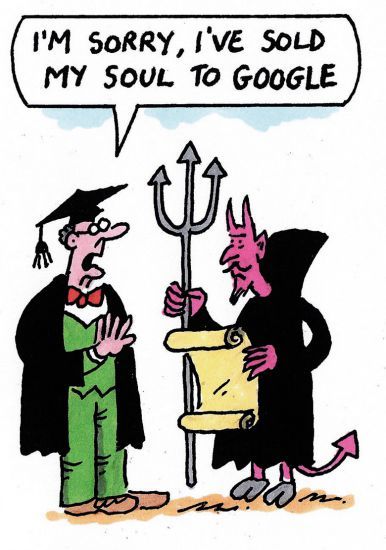

Google has secretly paid dozens of academics to produce research that it hoped would sway public opinion in its favour, The Times reported on 13 July. Some 329 pieces of research have been funded directly or indirectly by Google since 2005, of which two-thirds failed to declare the source of their funding, according to the US watchdog Campaign for Accountability, the paper said. Some papers that appeared in peer-reviewed journals lacked “basic academic rigour”, claimed the watchdog, which said many of the papers advanced arguments in Google’s favour as it appeals a $2.7 billion (£2 billion) fine from European regulators over fixing search results. On one occasion Eric Schmidt, Google’s former chief executive, cited a Google-funded author in written answers to Congress to back his claim that his company was not a monopoly – without mentioning that it had paid for the paper, the investigation found.

Lord Adonis’ call for vice-chancellors to “show leadership and halve their salaries” was unsurprisingly ignored last month, but the former Labour education minister returned with vigour to the subject of high senior pay in universities. In a House of Lords debate on 13 July, the peer called on the government to “cut vice-chancellors’ pay” and accused University of Bath vice-chancellor Dame Glynis Breakwell of “greed” over her £451,000 salary, including benefits, in 2015-16. Lord Adonis – one of the architects of tuition fees – noted that Dame Glynis’ additional directorships and benefits took her total pay package to “almost exactly half a million pounds – more than three times the prime minister’s salary”, later repeating the attack to a slightly larger audience on Radio 4’s Today programme on 14 July. Lord Adonis’ fury at the Bath situation seemed genuine, although it was rather belated – with Times Higher Education having broken the story in January.

Sir Michael Barber, chairman of the new Office for Students, which will be the English sector’s new regulator, had an early taste of what it is like to deal with academics. Sir Michael, former head of the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit under Tony Blair, had written a letter to The Guardian defending the organisation against an attack from his former government colleague Lord Adonis (who has been doing plenty of attacking). There are “significant risks ahead, but none so great as risk aversion,” Sir Michael had written. Jane Caplan, emeritus professor of modern European history at the University of Oxford, replied with her own letter criticising Sir Michael’s “content-free vision” as taking “meaningless management-speak to a new level of baffling rhetorical vacuity”. Another letter writer, Gerry McMullan, referred to Sir Michael’s background in public sector reform and asked if he was “still trying to fatten pigs by weighing them”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login