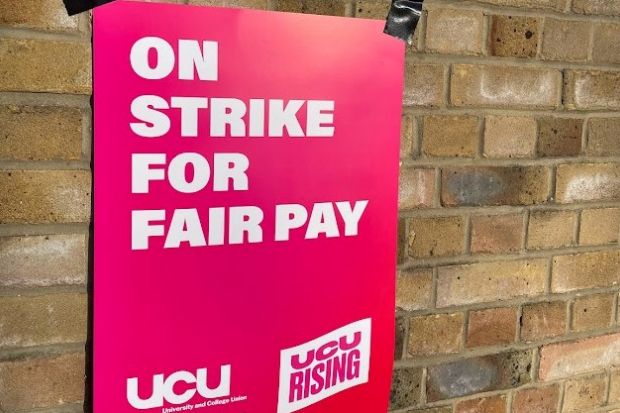

Academics taking part in a marking boycott in the UK have accused university leaders of attempting to undermine the integrity of the degree-awarding process in their efforts to ensure disruption does not prevent students from graduating.

As exams and coursework deadlines neared, the University and College Union-organised action – part of its long fight over pay and conditions – was threatening to affect graduations, with institutions putting measures in place that could allow them to bypass their regular procedures in the event of long delays.

The union's general secretary, Jo Grady, called it a “national scandal brewing that will impact hundreds of thousands of student graduations unless university bosses change course.”

But leaders have defended the measures, saying their Covid-era student populations had been through enough and individually they were unable to resolve a national dispute. The Universities and Colleges Employers Association (Ucea) said feedback from its members had indicated participation in the boycott was still low, with half of the institutions that responded to its survey saying ‘less than 10 per cent of students’ will be affected.

Raj Jethwa, the chief executive of Ucea, said it was up to individual institutions to decide how to grade work, but they would “do everything they can to ensure that this targeted boycott neither undermines the educational experience nor disrupts the ability of students to move on to the next stage of their education or careers.”

The University of Edinburgh attracted widespread attention after its students spoke out about fears that measures there could mean that marks for their 10,000-word dissertations would not count towards their overall degrees.

An open letter signed by more than 600 members of staff expressed “alarm and dismay” at the plans, which they said included stripping exam boards of “necessary expertise and the oversight of external examiners, and to disregard work submitted during the boycott when calculating degree classifications”.

One signatory, David Farrier, a professor of English literature, said there was concern at the university’s approach.

“No one knows what will happen in practice, and we hope that common sense will prevail,” he said. “But we are worried that the impact on students could be considerable. It is not clear that academic standards can be maintained if the full range of variations to normal practice are implemented. It would be better for all concerned if the dispute was resolved quickly.”

A university spokesman said it was “making every effort to provide results, degree-award outcomes and progression decisions to students by the published timelines”.

Its “range of temporary variations” were aimed at providing “greater flexibility to marking assessments”, he continued, adding that they would only be used “in the event that activities have been significantly disrupted”.

Industrial relations expert Gregor Gal, a visiting professor at the University of Leeds, said the example highlighted the “disruptive impact” of the boycott, “despite the high level of pay docking and attempts to pressure staff into marking”.

But, he said, other universities with less strong branches of the union might struggle to ensure academics were participating in similar numbers and it was difficult to ascertain how big an impact the boycott was having elsewhere.

The University of Cambridge was also considering introducing “exceptional” measures, to be used, if needed, to ensure students were awarded degrees on time, but a vote at the university's governing body, Regent House, rejected the changes.

Staff had made representations highlighting the potential impact of the boycott, including causing students to lose job offers or opportunities for further study due to delayed graduations.

Bhaskar Vira, Cambridge's pro-vice-chancellor (education), said in a message to students that he accepted the outcome of the vote, although the “impact on students is regrettable.”

“The measures that the university was seeking to help students complete their degrees and progress will now not be available. We will continue to make every effort to get work marked but this vote does mean that there will be longer delays for more students,” he said, adding that the powers sought by the university were “widely available across the higher education sector and, if available, would have enabled more students to graduate, without compromising academic standards.”

Professor Gal said few universities would be deterred from taking similar measures, despite the publicity Edinburgh and Cambridge had received, “as not trying to getting marking and assessing done by waiting for a resolution to the national dispute is not a ‘runner’.”

The developments prompted one degree accreditor, the Institute of Physics, to remind departments that all project work should be marked and any temporary changes to assessments must be agreed in advance. “It cannot be assumed that changes that were permitted under the extreme conditions of the pandemic will be permitted due to strike action,” a statement said.

Part of the reason institutions were considering such measures was the difficulty in ascertaining who is taking part in the boycott – with participation uneven across different departments – and the union reminding members they were not obligated to inform employers of their intention to take part.

At the University of Wolverhampton all staff received an email asking them whether they were participating and saying that those not responding by a set deadline would be assumed to be involved. A spokesman said this was done “so we could take reasonable steps to mitigate impacts on students in time for their marks to be considered by scheduled exam boards, so colleagues in finance could implement any necessary changes in a timely fashion”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login