A raft of gender initiatives put in place at a UK learned society has boosted the success rates for women applying to a prestigious fellowship scheme after a historic low.

It is two years since the Royal Society announced that only two women had been successful at securing its University Research Fellowships. The fact that 41 men received grants under the same call left the science community aghast.

But despite new figures showing that female success rates for the fellowships have now risen to be more in line with men, the whole incident has raised questions globally over whether research funders are doing enough to tackle gender bias in grant applications.

Although various provisions to support women have been established worldwide, experts believe that funders may still be missing what is actually happening to female applicants. Does looking at aggregated success rates data tell the whole story about how funding decisions are made, for example, and could certain initiatives to support women be part of the problem?

The European Research Council, which runs highly competitive funding schemes for basic research, established a Working Group on Gender Balance in 2008 to closely monitor the funding process.

The ERC has adopted a number of measures to support female applicants, including the introduction of a standard CV format that gives less scope for researchers to oversell themselves, and extending the eligibility period for early career awards for researchers with children.

But Dame Athene Donald, professor of experimental physics and master of Churchill College, Cambridge and a member of the ERC gender working group, said that it is yet to make allowances for part-time working and despite all the initiatives the “problem is not yet cracked”.

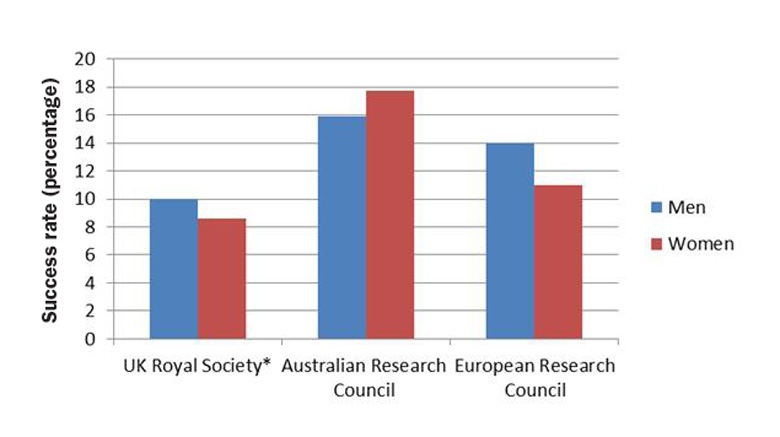

Helene Schiffbänker, deputy head of the Technology, Innovation and Policy Consulting group at Austria's Joanneum Research institute, said that ERC success rates have been “systematically lower for women over the years” (see graph for 2016 data).

A yet-to-be-published study, in which she and colleague Peter van den Besselaar, professor at VU Amsterdam, analysed the data for ERC early career grants for 2014, has found considerable differences in gender bias in different subject areas, or “domains” as the ERC calls them.

Gender bias negatively affected women applying for grants in the life sciences, for example, but for women applying for physics and engineering funding there was evidence of positive discrimination, she said.

The extent of gender bias even varied between decision-making panels within the same domain. “Panels differ considerably in [the] success rates of females compared to male applicants,” said Dr Schiffbänker.

This means that aggregating success rates across an entire funding call may not describe the “true gender fairness for an individual applicant”, she added. “The differences that applicants face disappears”, she said.

Dr Schiffbänker said that at the ERC there is no binding definition of excellence or a formalisation of the peer review process so “decisions are made on an individual basis” and this can mean gender stereotypes are “activated”.

Early career award schemes 2016

The approach to the situation in Europe differs from that in the US, according to Meg Urry, director of the Yale Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics. “Europe has more top-down and interventionist approaches,” she told Times Higher Education.

“US funding agencies are on record as supporting gender equality, of course, but there have not been many initiatives per se. In a climate where every metric we use for advancement has been shown experimentally to be biased against women, something more obviously needs to be done,” she added.

The US National Science Foundation, which funds about one-quarter of all basic research in universities and colleges nationwide, offers no-cost grant extensions for researchers who have a child during a project. It said that overall, for grants at all career stages, men and women are funded at roughly the same rate.

At the Australian Research Council, women have been more successful than men at securing early career funding since 2014. In November last year, it launched the Gender Equality Action Plan 2015-16, which has instigated unconscious bias training among assessors and peer review reform.

But Lisa Adkins, chair of sociology at the University of Newcastle Australia, said that although she welcomes the initiative, its time frame is “incredibly short”. “The production of gender inequality is an ongoing process and needs to be constantly rather than intermittently addressed,” she added.

Professor Adkins said: “There is also a danger in the proposed initiatives that gender equity is reduced to issues of family and motherhood for women. This locates the ‘problem’ in the private sphere and absolves workplaces, and the practices of research councils themselves, of responsibility.”

In the UK, women have had far more success at securing funding as part of the Royal Society’s University Research Fellowships this year compared with two years ago, although far more men still apply. A total of 10 women out of 116 applicants were offered a fellowship compared with 35 out of 350 men.

Uta Frith, chair of the Royal Society diversity committee that was established in the wake of the controversial 2014 round, where women had just a 3 per cent chance of winning funding, said that its actions have included sending representatives to universities that put forward fewer female applications than expected.

The 2014 awards triggered intense scrutiny of the whole grant awarding process, from the number of female applications through to the number of women shortlisted, interviewed and offered funding. It revealed that women apply for funding at a lower rate than men – a common theme among all the research funders contacted by THE.

“We have now convinced ourselves that with the grants there isn’t a bias because the fellowship offers completely match the pool size of the applications since 2014,” said Professor Frith.

The general consensus now is that 2014 was probably a “statistical blip”, she added. But it did “serve as a wake-up call”. “There was a general feeling that something needed to be done…not just in this country but worldwide,” she said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login