Research concentration is a debate that can take many different forms. For starters, there is the question of whether funding should be focused on “excellence”, although the meaning of this term is itself a highly contested one. Another aspect of concentration is geographical: does it aid research and economic growth to focus investment in one particular area, for instance?

But there is another side to concentration that may not always receive quite so much attention – the degree to which research in particular countries and institutions is specialised in different areas or, alternatively, covers all the disciplinary bases.

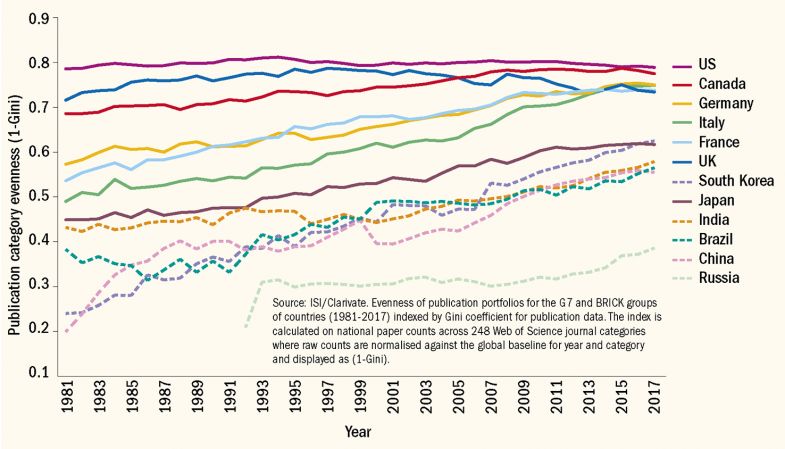

A new report from Clarivate’s Institute of Scientific Information attempts to analyse trends in “subject diversity” over the past 40 years by looking at the global disciplinary spread of research papers in the Web of Science database in each year, and then using this as a benchmark to look at individual national systems and institutions.

THE Campus resource: How to foster collaboration among students trained to compete

It finds that there appears to have been a convergence among developed systems in Europe and North America towards researchers covering a reasonably – although not completely – diverse set of disciplines, with some countries such as Germany and France becoming more even in subject mix over time.

Others, like the US, and particularly the UK, started with a relatively even mix but seem to have drifted towards more specialisation in recent years.

Meanwhile, rapidly developing systems in Asia, such as China, South Korea and India, appear to have started with a much more concentrated subject mix but have increased diversity over time, although the data raise questions about whether this diversity is now plateauing at a lower level.

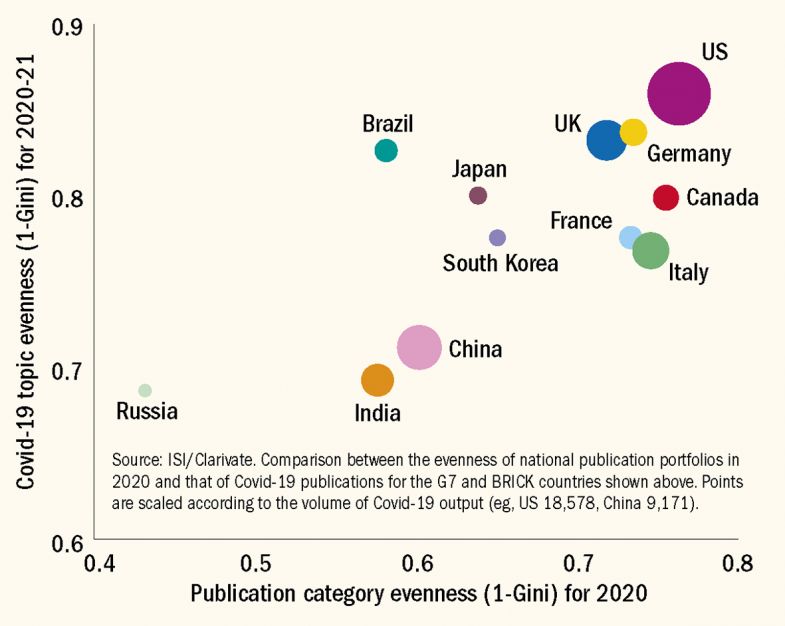

The analysis goes on to look at the relationship between these subject mixes in different countries and the research response to Covid-19, suggesting that those nations with the most diversity had a more comprehensive disciplinary response to the pandemic.

Disciplinary spread of research over time

Jonathan Adams, chief scientist at the ISI and visiting professor at King’s College London’s Policy Institute, said that as with diversity in other areas such as ecology, more diverse systems were built to withstand shocks because they were more prepared for every eventuality.

An example from the data was Brazil, which had a relatively more comprehensive research response to Covid despite having lower subject diversity, but this was possibly because it had greater specialism in medical areas.

“The important issue is you don’t know what the next crisis is going to be. This time it was Covid and Brazil was positioned to respond to Covid in a better way than China or South Korea in research terms. Next time it might be something different. Diversity gives you that capacity for resilience,” he said.

He said that the general convergence of North American and European systems around a level of subject diversity to a large extent reflected the internationalisation of the science system.

Subject diversity and Covid research strength

However, the fact it was not occurring at the very top end of the “evenness” scale – expressed in the report using the Gini coefficient, better known for measuring income inequality – suggests that specialisation is still happening in each nation.

The drift towards specialism in the US and UK also raised other questions, Professor Adams said.

In the case of the UK, the report says that its “dynamics stand out as a saw-tooth of dwindling diversity, which may be an effect of its assessment system”.

Professor Adams said although this was a “speculative” observation, the past 15 years had seen a heavier focus on research assessment and the potential for departments to fall by the wayside if they did not make the grade.

“There has to be a question there about whether the unusual dynamics of the UK – which do look very different from other countries – are because it has such an intense research assessment system,” he said, where decisions “are partly conditional on those REF [research excellence framework] scores rather than…on objective judgements.”

He added that one of his key takeaways from the analysis was that decisions over which disciplines to pursue needed to be left to the scientists, and the apparent rise in diversity over time in most nations was a reflection of this.

“What that increase in diversity looks like [in the analysis] is an expression of a global consensus about where to conduct research. Effectively it is a global brains trust of leading scientists saying this is where we should be [working],” Professor Adams said.

For this reason, he said any government moves to direct research in a particular direction were undesirable, including intervention in initiatives such as the UK’s new “high-risk, high-reward” Advanced Research and Invention Agency (Aria).

“I think that it is dangerous to get into picking winners. That is where steering Aria really worries me” because it was an example of something “with a strong government influence and being set up as a concentration of money”.

However, an academic who has conducted influential work on subject diversity cautioned that adherence to the Haldane principle – that governments fund but scientists decide when it comes to research – was also fraught with difficulty.

“The Haldane principle is problematic because although we treat science as if there are no structures of power and privilege, there certainly are,” said Andy Sterling, professor of science and technology policy at the University of Sussex.

“If you leave it to the scientific community, then the existing structures of power and privilege inside science will actually drive research in some directions and not others. The Haldane principle doesn’t mean that politics doesn’t exist; it just means the politics that drives research is the politics inside the disciplines.”

Professor Sterling said that the alternative to this and to governments dictating priorities was to free research from both these types of constraints and allow all disciplines to flourish, even if their impact was not easily measurable.

Ludo Waltman, deputy director of the Centre for Science and Technology Studies at Leiden University in the Netherlands, said he saw “considerable risks” with assuming that disciplinary diversity could be summarised “in a single number” that could be improved.

“Inevitably priority-setting in science is a political process, in which different stakeholders have different interests, and trade-offs between these interests need to be made,” he said.

Ignoring this left “insufficient room for an open political debate about the pros and cons of different scientific priorities and the degree to which different priorities align with the specific situation in which a country finds itself”.

Professor Sterling added that in his view it was also very hard to measure subject diversity in research systems unless an analysis took account of how different disciplines were from each other – something termed “disparity” – otherwise you could end up with an assumption that subjects such as sociology and social work were just as different as astrophysics and history.

“When we talk about diversity in research as in elsewhere, the absolutely crucial property is the degree to which things are different from each other. By just measuring evenness and variety…by counting the categories, the main property of diversity is being missed,” he said.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Subject diversity makes strides across globe

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login