A US university has said that, despite anxiety over the burning of books by students protesting against an academic who urged racial harmony, it sees no action eligible for any punitive response.

Kyle Marrero, president of Georgia Southern University, told students at a meeting that officials had “been looking as hard as you have” at ways of holding responsible students who burned books written by Jennine Capó Crucet.

“In essence,” he conceded, according to the campus student newspaper, The George-Anne, “the First Amendment overrides the student code of conduct. So that is frustrating.”

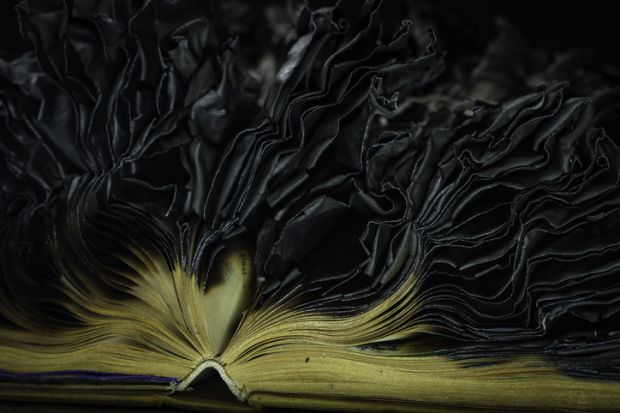

The book burning occurred immediately after an address by Dr Crucet, who teaches English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She visited Georgia Southern’s Statesboro campus as part of a tour to discuss her novel, Make Your Home Among Strangers, that reflects her experience as a Cuban-American at an Ivy League university.

Some students attending her event challenged the academic’s references to “white privilege”, complaining that her comments amounted to unfair generalisations.

After the event, a brief video posted to Twitter showed a small group of students laughing while feeding pages of her book into a fire on an outdoor cooking grill. Professor Crucet spent the night at a different hotel than she had planned, then cancelled a scheduled second appearance at Georgia Southern the following night.

While the video suggested no direct threat to anyone, book burning is an action with connotations of racial and ethnic violence, notably from its practice by Germany’s Nazi government in the 1930s.

The US Supreme Court, citing First Amendment protections, has generally upheld the right to stage protests that don’t include threats or intimidation aimed at others. It has specifically applied that reasoning in the case of burning crosses – an act popular among racists in the southern US in the decades after the US Civil War.

While some students at the community assemblies pressed Dr Marrero to somehow penalise participants in the book burning, leaders of the Georgia Southern student association backed his approach of emphasising broader consultation.

One of them, Kahria Hadley, a marketing and economics major serving as a student government vice-president, acknowledged that she was unpleasantly surprised by the book-burning incident at Statesboro, a 20,000-student campus where the majority are white and about a quarter are black.

“The Georgia Southern I feel that’s in the news is not the Georgia Southern that I know, that I came to love when I came to this school a couple of years ago,” said Ms Hadley, who is African American. But she expressed understanding. “Students who are maybe new to different concepts, as far as diversity and inclusion go, maybe just reacted differently,” she said, “because they just don’t know, or they’re just not educated on situations like this.”

While the incident was a setback to diversity efforts on campus, those involved should not face punishment, Ms Hadley said. “Every student has the right to do what they want, as far as freedom of speech,” she said.

Adam Steinbaugh, a lawyer with the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, said Georgia Southern was providing “a good example of how a healthy community” should respond by “fighting bad speech with more speech”. This included, he said, the campus newspaper extensively covering the event, its faculty working to put the action in historical context, and its administrators quickly and effectively communicating facts.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login