About a third of UK universities now award a first-class degree to at least a quarter of their undergraduates compared with just 8 per cent of institutions five years ago, a new analysis has shown.

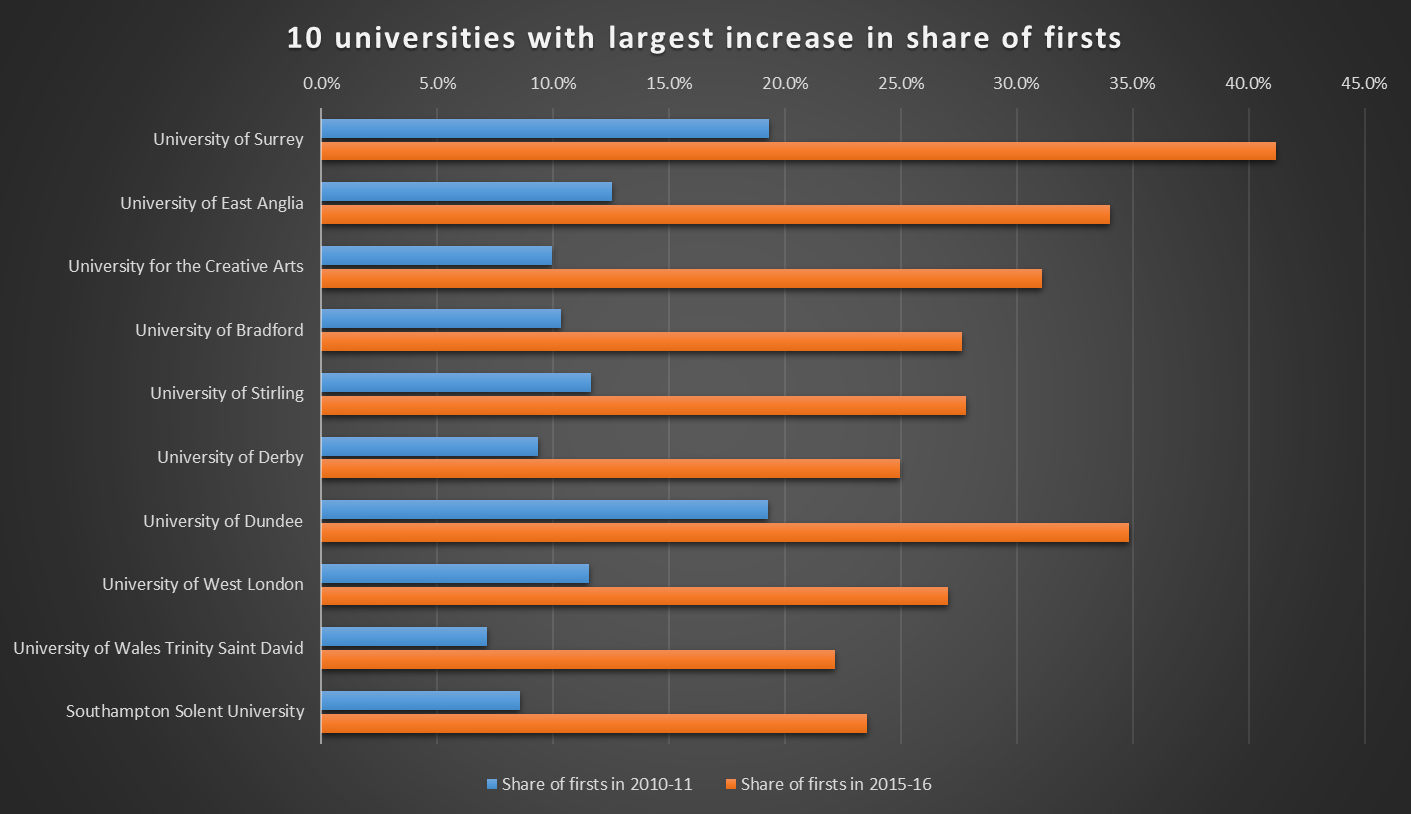

Figures on degree scores from the Higher Education Statistics Agency, analysed by the Press Association, show that 40 higher education institutions saw the proportion of firsts rise by more than 10 percentage points between 2010-11 and 2015-16.

At some the increase was more than 20 percentage points, including at the University of Surrey – which doubled the share of firsts it awarded from 19.3 per cent of classified degrees in 2010-11 to 41.2 per cent in 2015-16 – and the University of East Anglia, where the proportion of firsts almost tripled from 12.5 per cent to 34 per cent over the period. Among the Russell Group of large research-intensive universities, the University of Durham saw the biggest increase, with the share of firsts going from 17.8 per cent to 30.2 per cent.

Note: graph does not include small and specialist higher education institutions.

Rising entry standards for students were cited by some universities as one explanation.

Neil Ward, pro vice-chancellor (academic) at UEA, said that the average entry qualification level of graduates had been about 20 per cent higher in 2015-16 than in 2010-11, while the university had also “focused on improving teaching staff numbers” to improve its student-to-staff ratio from 18:1 to 13.3:1.

Alan Houston, pro vice-chancellor for education at Durham, said that it had increased its entry requirements and has seen “a concurrent rise in degree outcomes for our students”. He added that external examiners “routinely confirm that the academic standards of student work [at Durham] are comparable with similar programmes elsewhere”.

Meanwhile, Jane Powell, vice-provost for education and students at Surrey, said that the increased share of firsts reflected “a combination of national trends” and the university’s “concentrated focus on enhancing all aspects of our educational provision”.

The jump in the share of firsts from 33.9 per cent to 41.2 per cent in the year to 2015-16 will also be part of a standard annual review into marks at Surrey.

The new analysis is likely to fuel the debate about rising marks at UK universities: already in January, figures from Hesa showed that, overall, almost three-quarters (73 per cent) of students at UK universities gained a 2:1 or a first in 2015-16. The share was 60 per cent in 2010-11.

David Palfreyman, director of the Oxford Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies, said that it was very difficult to pinpoint exactly what was causing the rise in firsts.

“Since undergraduates do not pay more fees to ‘buy’ a first, I doubt it is fees that explains this particular growth,” he said, although he asked whether factors related to fees could explain “the broad shift to ‘2:1s for all’ compared with the 2:2 being the norm [in the past]”.

He said that the rising share of firsts still raised questions about grade inflation, including the role played by changing student assessment methods, performance management, the external examiner system and casualisation of the teaching workforce.

However, he added that it was also possible that students were better prepared, worked harder and were better taught than before.

Others pointed to the knock-on effect of employers making a 2:1 the minimum standard for graduate candidates in recent years.

However, Martin Birchall, managing director of graduate recruitment market research firm High Fliers Research, said that the number of employers insisting on a 2:1 degree had “dropped significantly” in the past three years and noted that more employers than ever were accepting 2:2s in a bid to have “as diverse an intake of graduates as possible”.

simon.baker@timeshighereducation.com

Full table of share of firsts at UK higher education institutions, 2010-11 and 2015-16

Source: Hesa, analysis by Press Association. Note: List includes only comparable institutions. Figures rounded to one decimal place.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login