The power of university networks is not that they determine institutions’ agendas but rather that they enable leaders to work on their missions with “trusted friends”, according to Jaap Winter, president of VU University Amsterdam and founding president of Aurora, a new group of nine European universities.

Speaking at the launch of the network in Amsterdam on 21 October, Professor Winter said that university partnerships are about “being able to do things that you are struggling to do with friends who can teach you how”.

He told Times Higher Education that Aurora – whose other members are Grenoble Alpes University, the University of Aberdeen, the University of Antwerp, the University of Bergen, the University of Duisberg-Essen, the University of East Anglia, the University of Gothenburg and the University of Iceland – differs from other networks in that it has a strong focus on increasing diversity in academia and improving teaching and the student experience, as well as helping to solve global challenges through research.

He said that the group plans to develop a prize for an outstanding initiative on diversity undertaken by one of the universities.

“We see a lot of automatic academic exchange happening. We don’t need to build a network for that. But thinking of innovation in teaching – we don’t see many networks involved in that,” he said.

David Richardson, vice-chancellor of the University of East Anglia, added that the group will not just connect the leaders of the university, but will promote collaboration at all levels, including students, sports teams and student groups, such as LGBTQ societies.

But Aurora is not the only European University network to launch this year. The Guild of European Research Intensive Universities, a group of 15 institutions from across the Continent, was unveiled in June and will officially begin work later this month.

Last year, the European Women Rectors Association was founded to promote the role of women and to advocate for gender equality in academia as a continuation of the European Women Rectors Platform, which has organised biennial conferences since 2008.

Speaking at the launch of Aurora, Lesley Wilson, secretary general of the European University Association, which was launched in 2001 and has 850 member institutions, said that the establishment of university networks spanning the Continent began with the Coimbra Group in 1985 and the Network of Universities from the Capitals of Europe (Unica) in 1990, following the initiation of European funding programmes that led to closer interaction between institutions.

She added that the rise in small networks of universities more recently – such as Universitas 21 in 1997 and the League of European Research Universities (Leru) in 2002, as well as Aurora and the guild – can be attributed to the changing missions of universities during the past 15 years.

“All the main challenges universities face wouldn’t necessarily have been on the table 15 years ago,” she said, citing increased competition for students and researchers, technological advances and decreased public funding.

She said that these changes mean that universities “need to be more strategic in identifying their mission”.

“It seems to be [that university networks] are part of the landscape of the future, as long as institutions can find the right partners,” she said.

Ole Petter Ottersen, rector of the University of Oslo and chair of the Guild of European Research Intensive Universities, agreed that research and education have become “more and more European” in the wake of the Bologna Process and the launch of European Union-funded research and mobility programmes.

He added that other regions of the world, particularly Asia, are increasing public spending in research and innovation and that European higher education “will risk being dwarfed” if the countries do not “increase emphasis” in these areas.

Research collaborations across borders are also needed to tackle “grand challenges” in society, he said, noting that one university “cannot possibly command the competence and the clout that is needed to tackle the challenges ahead”.

He said the guild aims to have about 20 member institutions so that it is “large enough to have a strong voice and small enough to ensure all institutional leaders will be able to gather”.

Professor Winter added that a benefit of small university networks with a wide variety of institutions is that universities can share ideas that would be “difficult” if a “straight competitor [was] sitting next to you in the room”.

The small size of Aurora and the proximity of the institutions means that the group can visit any other member within two to three hours and do “genuine work together”, Professor Richardson added.

He denied that the network was launched in order to safeguard collaboration with European universities post-Brexit, stating that the group has been in the pipeline for the past 18 months.

Instead, he said, he “recognised the added value of being part of a strong network of universities in an increasingly global higher education system”.

However, Professor Ottersen said that the guild “should be seen as an antidote” to the negative consequences that Brexit might have on educational and academic cooperation, noting that the UK’s departure from the EU “reverses” the trend of the dismantling of research borders across the Continent since the Second World War.

Sir Geoffrey Adams, the British ambassador to the Netherlands, told Aurora that there is no doubt that such partnerships will be of increasing benefit once the UK leaves the EU.

He said that he had intended to attend the network launch event “months ago”, but the EU referendum vote on 23 June “turned what was previously pencil in my diary into ink”.

UK universities will have to collaborate “in ways that don’t rely on joint membership of the EU”, Sir Geoffrey said.

Whatever the individual missions of these groups, Sir Ian Diamond, vice-chancellor of the University of Aberdeen, warned Aurora that university networks are “arid, dry and useless” unless they are “accompanied by a clear operational plan” and monitor success over time.

“We wouldn’t be here unless we were committed to doing that,” he said.

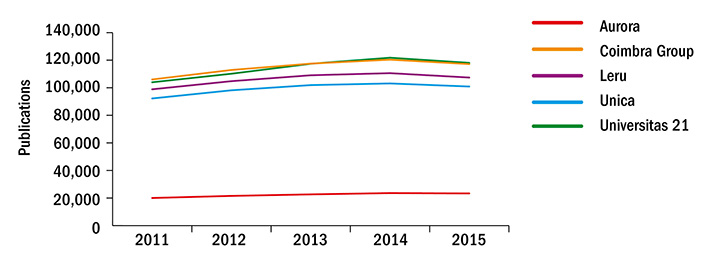

Research strengths of university networks

Universitas 21 has the highest research publication output among five university networks analysed by Elsevier for the launch of Aurora, while the new network has the most research impact.

The research commissioned by Aurora found that the member universities of Universitas 21 published 118,054 papers in 2015, more than Coimbra, Leru, Unica or Aurora.

Coimbra had the highest publication output when publications between 2011 and 2015 were counted, with 573,947 in total, compared with 571,405 for Universitas 21.

Source: Elsevier Research Intelligence

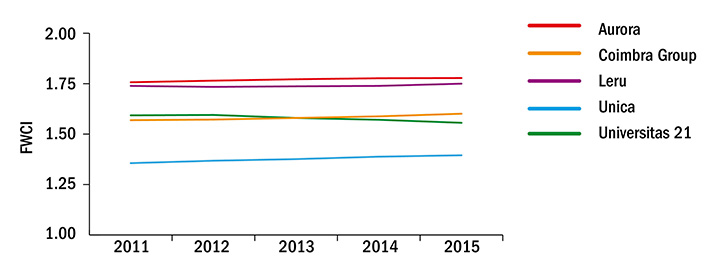

However, when the five mission groups are ranked by their field-weighted citation impact, which weights citations based on the total number of citations in a subject field, Aurora tops the list with a score of 1.769 between 2011 and 2015. A score of 1 denotes the world average.

The new group has also seen the greatest growth in publication output during the four-year period (3.89 per cent), while Unica has seen the greatest growth in citations (0.71 per cent).

Source: Elsevier Research Intelligence

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: European networks on the rise

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login