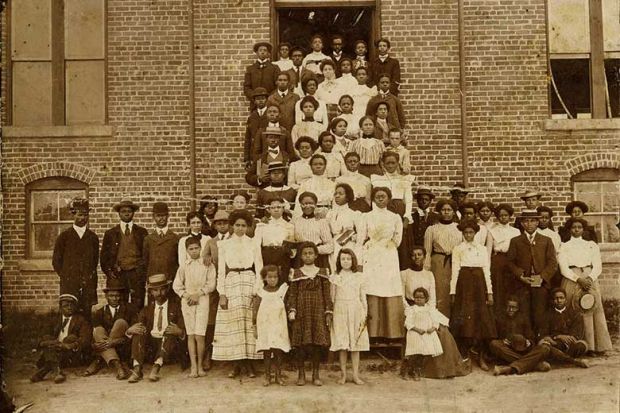

The fight to save one of only two all-female historically black colleges in the US is seen as exemplifying the challenges facing small universities in the country.

Bennett College, a 145-year-old institution, needs to find $5 million (£3.9 million) by the end of this month to prove its financial health to an accreditor that voted last month against its continued operation.

“I think we’re going to make it,” Bennett’s president, Phyllis Worthy Dawkins, said amid an almost non-stop fundraising campaign. Bennett alumni and a few public figures have taken up the cause, ramping up attention through social media.

Their progress so far – about $1 million in the first month, with three weeks remaining – does not seem sufficient, though Dr Dawkins is also pursuing loan forgiveness options and preparing to sell campus assets as needed.

The bigger question, if she and Bennett succeed by their 1 February deadline, may be: for how long? At least three major categories of US colleges are facing strong financial headwinds these days – small privates, minority-serving, and women-only – and Bennett is all three.

The US now has 101 historically black colleges, down from 121 in the 1930s, and about 60 women-only colleges, down from 281 in the 1960s. And while Bennett is known – along with Spelman College in Atlanta – for serving only black women, Dr Dawkins saw neither category as her biggest financial burden.

Instead, she pointed to data showing that private US colleges, because of demographic changes and other factors, are now closing at a rate of about 11 per year and accelerating. Dr Dawkins needs to look only a few blocks away in downtown Greensboro to see the 12,000-student North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, another historically black college that has the considerable advantage of public investment.

“It’s about being a private institution without state support,” Dr Dawkins said of Bennett’s probationary status with its accreditor, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. It is Bennett’s third period of warning by Sacs since 2000. And the college’s enrolment of 463 is barely half what it had a decade ago.

That decline stands in contrast to abundant research detailing the advantages felt by women attending women-only colleges, and by black students attending historically black institutions. Such institutions provide nurturing environments that produce success rates beyond what many students experience at traditional white-majority or male-dominated campuses.

Bennett is evidence, said Lisa Wolf-Wendel, a professor of higher education at the University of Kansas, that speciality-focused colleges remain valuable. “It’s one thing to admit women or to admit African Americans – it’s another thing to actually be institutions that serve them,” she said.

The enduring need for such places isn’t the issue, agreed Walter Kimbrough, president of historically black Dillard University. “HBCUs are harder to run because the population has less wealth,” he said.

Even if Bennett succeeds this time around, Dr Dawkins acknowledged, major changes still need to be made – including the possibility of giving up either its women-only or minority-only status.

“We are open to different models – I don’t make the final decision on that,” she said. “As president, we just cannot be here again.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login