Click here for the full graph with each university listed

New research has laid bare the link between high dropout rates and universities that take undergraduates from low socio-economic backgrounds – and which institutions are managing to buck this trend.

It demonstrates how widening participation could have a financial cost for institutions, at a time when extra funding for universities that take on students from poor backgrounds is under threat.

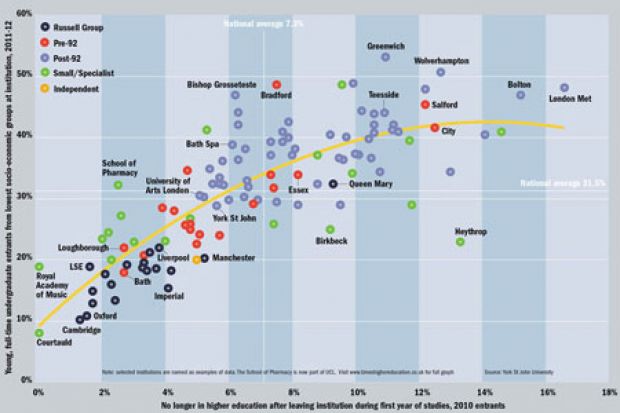

The graph below, created by York St John University, shows a clear correlation between retention at English universities and the proportion of students from a household where the highest-earning family member had a job falling into the bottom half of the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification.

However, this correlation appears to break down when the dropout rate exceeds 12 per cent in the righthand third of the graph.

Les Ebdon, director of the Office for Fair Access, said the research “starkly” illustrates the costs of taking on students from a widening participation background because of the “significant loss of money” to an institution when a student drops out.

“If universities were simply businesses they wouldn’t do it,” he said.

This emphasises the importance of the Higher Education Funding Council for England’s student opportunity allocation – previously known as the widening participation premium – which gives extra money to universities that take disadvantaged students, he argued.

This year, the allocation is worth £332 million, down £34 million from 2012-13, and there are fears that it could be cut further as the government looks for savings over the next two years.

Professor Ebdon said the fund covered only a “fraction” of the cost to a university of a student dropping out.

It distributes nearly £300 per full-time student multiplied by a “risk weighting” based on the average age and qualifications of the institution’s student body – a proxy for how likely students are to need extra support.

But when students drop out, universities face the loss of tens of thousands of pounds of tuition fees, teaching grants for higher-cost subjects, and fees for accommodation and other services.

According to Graeme Atherton, director of the National Education Opportunities Network, there was a perception among some academics that students from poor backgrounds “are hard to teach, expensive and drop out”.

“I’ve encountered it not infrequently,” he said. “[There is a] perception that they are a burden, and this [research] adds to that idea.”

The universities on the right of the graph take a “big finance hit”, he said.

But the research does offer hope to the sector as it shows that the institutions in the top left of the graph are managing to combine low dropout rates with a high percentage of widening participation students.

York St John has managed to cut its dropout rate from more than 10 per cent in 2003 to 5.6 per cent in 2011, although its proportion of widening participation students decreased slightly in that period.

Andrew Fern, strategic analyst at York St John, said the institution had improved student feedback and instituted a survey that looked for early warning signs that students might drop out.

Dr Atherton noted that institutions with lower entry grades would be more likely to attract widening participation students, who were often less academically prepared, and so less likely to stay the course.

Tessa Stone, chief executive of the education charity Brightside, cautioned that although entry grades explain the correlation at some institutions, the graph also showed that some institutions with equally high entry grades had very different dropout rates.

University location, number of international students and course quality could all make a difference to retention, regardless of students’ performance before university, she said.

She also warned that the problem could be a vicious circle, because when students see their peers drop out this “reinforces the fact that it’s possible”.

“It’s not simple,” said Professor Ebdon. “Money is clearly quite important. The poorer you are, the less likely you are to stay on course.”

He added: “A sense of belonging is critical to student success. If you feel you don’t belong either because of class or ethnicity, you’re more likely to drop out.”

Those from widening participation backgrounds might not have been as well prepared by their previous education for university as others, he continued, which pointed to the importance of university-run access courses.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login