A wide variation in different countries’ success in tackling Covid-19 could lead to major winners and losers in the coming battle to recruit international students, it has been predicted.

Perceptions that some nations have struggled to contain the outbreak could be the difference between university sectors losing either millions or billions of dollars, according to calculations by Times Higher Education.

Dire predictions about the losses that some universities could sustain were amplified last week after a report suggested that the pandemic could result in a drop in new overseas enrolments at UK universities of almost 100,000 students, a fall of close to 50 per cent.

But global education experts familiar with how international student mobility has changed over the past two decades suggest that such a dramatic downturn in recruitment might not necessarily be replicated everywhere.

Jamil Salmi, former tertiary education coordinator for the World Bank, told THE that there was plenty of evidence from recent years of students shifting their overseas study preferences.

Examples include the number of Indians studying in Australia almost halving from 2010 to 2012 after a number of racist attacks in the country and the effect on recruitment of the UK’s (now reversed) decision in 2012 to end post-study work visas.

“I do think that international student flows are very reactive to what happens,” said Dr Salmi, adding that the main factors influencing decisions about where to study abroad were a country’s visa regime, financial costs and general considerations such as safety.

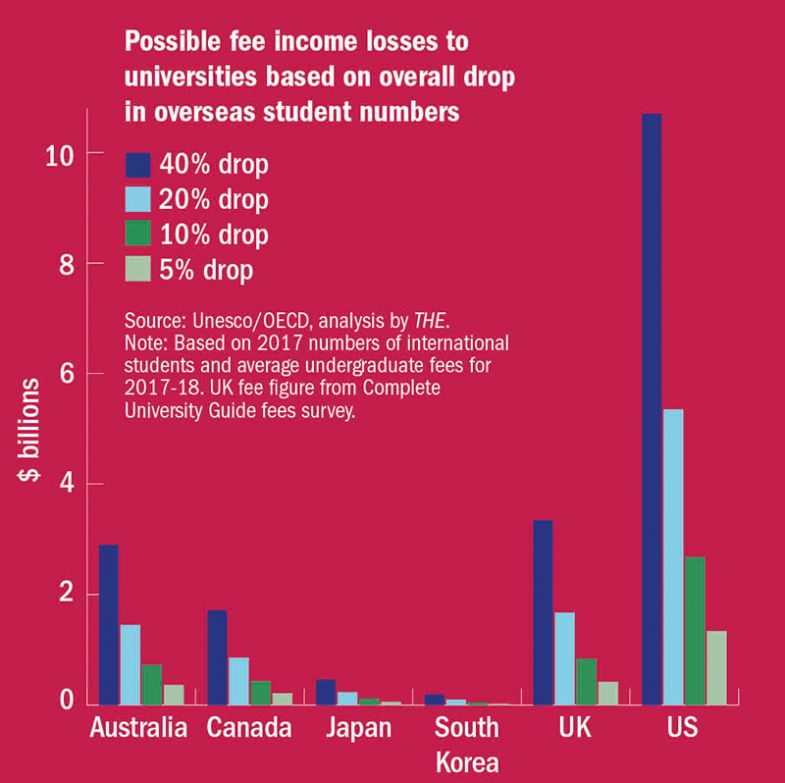

On the line: Potential cost of drop in international student traffic

Potential evidence that students might consider countries’ handling of the Covid-19 crisis can be found in recent surveys of prospective students in key nations such as India and China.

For instance, British Council survey data suggest that almost 80 per cent of Chinese and about two-thirds of Indians planning to study abroad are currently very concerned about health and well-being in host nations.

The same surveys have pointed to between 20 per cent and 30 per cent of Indian and Chinese students who have applied for a course saying that they had already cancelled or postponed their plans or were likely to do so. A further 40 per cent in China and 14 per cent in India were undecided.

Dr Salmi said international students might well scrutinise different countries’ handling of the coronavirus crisis, and even if English-speaking nations remained their favoured destinations, they might choose to switch where in the Anglosphere they study.

“You still have Australia, New Zealand and Canada that have handled [the crisis] much better than the UK or the US, and these are also English-speaking countries,” he said. “The prestige of UK and US universities will help, but still we might see some shifts, and a 10 per cent shift is a big amount of money.”

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, told THE that “Covid-19 and the tardy and inadequate responses, especially by the US and the UK governments”, were factors affecting Chinese decision-making on Western education.

He predicted that, more broadly, there might be a shift towards Asian destinations, even after the pandemic is over.

“Most of the previous demand for English-language country education will restore, but there will have been an uplift in the demand for China, Japan, Korea and also − if Taiwan permits more entry − Taiwan,” Professor Marginson said.

In its own assessment of the international higher education landscape earlier this month, credit ratings agency Moody’s pointed out that “over the next year, international student demand will be even more affected by national reputations”.

“The impact across countries could vary significantly depending on international students’ perception of how individual governments have handled the outbreak and how safe they are likely to feel living there,” its briefing note added.

Data on international student numbers and tuition fee levels from Unesco and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development suggest that major variations in recruitment could see university systems in the US and the UK losing billions of dollars while others, such as Australia and Canada, restrict the hit to hundreds of millions.

Other countries that could gain in terms of recruitment as a result of their handling of the coronavirus crisis include Germany – although with most of the country’s universities still not charging for tuition, any financial gain would mainly be to the wider economy.

However, Anna Esaki-Smith, managing director of the Education Rethink consultancy, said that although country variations might be possible, she thought “there is a greater likelihood that the unresolved nature of the outbreak will result in caution about leaving home as a whole”.

What might make a difference, she added, would be universities cutting fees. “Students and their families could well base their study-abroad decisions simply on value, more than anything else,” she said.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Students may be steered by countries’ Covid policies

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login