Lower rates of protection provided by the University of Oxford’s vaccine compared with those created by the pharmaceutical industry should not obscure the “amazing success story” that will benefit academic science for years, drug development and science policy experts have said.

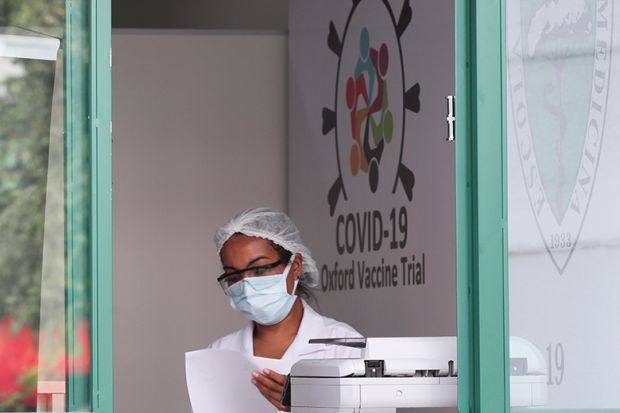

According to clinical trial results reported by the Oxford Vaccine Group, its Covid jab is 70 per cent effective on average, with its main dosing regimen effective for 62 per cent of those who received it and a smaller trial, which accidentally used a half dose-full dose combination, showing 90 per cent efficacy.

Higher-cost vaccines developed by drug companies Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech, however, had efficacy rates of 94.5 per cent and 95 per cent respectively.

Neither the Oxford vaccine’s lower effectiveness nor the failure to publish full phase III results before other vaccine candidates should deflect from the scale of the university-led group’s achievement, insisted Kenneth Kaitin, director of the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development at Tufts University in Boston.

“The fastest development for a vaccine prior to Covid was for mumps, which took four-and-a-half years, so no one could have guessed we would have reached this point within eight months,” Professor Kaitin told Times Higher Education, adding that the “incredible speed” of vaccine development was an “amazing success story” for both academic science and big pharma.

Any criticism of Oxford’s failure to publish full phase III results before Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech was also misguided given the “billions of dollars and decades of experience” that the pharmaceutical industry could draw on, said Professor Kaitin, who added that Moderna’s RNA-based vaccine was also “relatively easy to synthesise” compared with the technique deployed by Oxford, which reengineers a harmless adenoidal virus from a chimpanzee to include genes from the Covid virus.

“When it comes to designing clinical trials or recruiting patients, academia cannot compete with industry,” he added, explaining the costs of pursuing this kind of project meant “academics are often strangers to translational research”.

“No one should think it was a failure if Oxford was not the leader in getting their product to market,” he added.

If Oxford’s vaccine were several months behind other Covid vaccines, it would still be immensely useful, said Professor Kaitin, who observed the “need for lots of different vaccines, which will serve different purposes”.

“Those vaccines which require ultra-cold storage are important, but if Oxford/AstraZeneca come up with a vaccine that is easily transported, that will also be crucial, particularly for the lower-income countries,” he said.

Even if Oxford’s vaccine is not licensed in some countries − with some US-based industry analysts predicting the product will “never be licensed in the US” after officials raised concerns about how clinical trials were handled − these efforts to rapidly produce a vaccine will not have been in vain, added Professor Kaitin.

“I would be surprised if any institution decided this had been a waste of time – universities will have learned so much in terms of dealing with future pandemics, and the work on RNA can be used for lots of different things,” he said.

Joe Marshall, chief executive of the UK’s National Centre for Universities and Business, said the success of an Oxford vaccine would help to underline the importance of increasing research funding for universities.

“This development was only possible thanks to the UK’s long-term research base that has been built up for years at Oxford and other universities,” said Dr Marshall. “Not all research will be front-page or top-of-the-bulletin news in the same way as this vaccine, but it still shows the importance of fundamental research because, without it, we cannot have translational research,” he added.

Oxford’s successful partnership with AstraZeneca when developing the vaccine was also important for UK science policy, Dr Marshall added. “It is fantastic because it shows how the UK’s research base can interact with a commercial partner to solve huge challenges,” he said, adding that it is likely to bolster the case for schemes such as the knowledge exchange framework and the Higher Education Innovation Fund, which seek to encourage links between academia and industry.

Sarah Chaytor, director of research strategy and policy at UCL, said the Oxford vaccine would be a useful reminder of the “incredible national effort from all our universities during the pandemic”.

“Whether through sequencing the genome of the virus through the COG-UK [Covid-19 Genomics UK] consortium, developing new vaccines, modelling the spread, monitoring the impact on people or developing breathing aids [at UCL] and other treatments – it shows the ingenuity and dedication of the UK’s researchers and the ability of our research base to work in partnership with hospitals, industry and others to rapidly mobilise essential knowledge and expertise,” said Ms Chaytor.

“It will reinforce the critical importance of investing in a sustainable research base to enable continued excellence, development of talent and fostering partnerships that make a real difference to people’s lives,” she concluded.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Oxford result is ‘wider win for academic science’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login