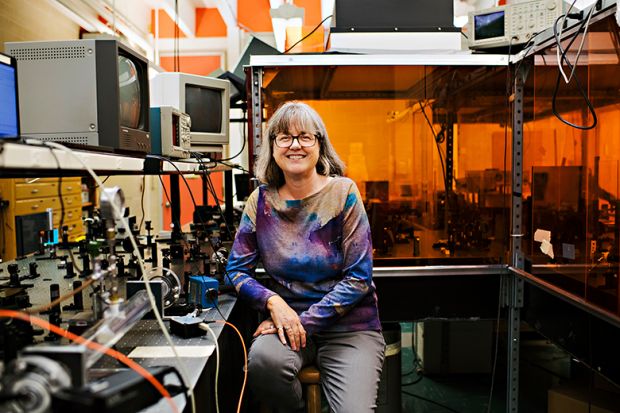

Nobel laureate Donna Strickland has described how becoming only the third woman in history to win the physics prize turned her into a “rock star” overnight – but has urged people not to focus too much on her gender.

Dr Strickland, associate professor in physics at the University of Waterloo, became the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Physics for 55 years when her role in the discovery of a new way of generating high-intensity laser pulses was recognised.

Speaking to Times Higher Education, Dr Strickland expressed surprise that many observers had focused on the fact that she did not hold a full professorship and had linked this to the challenges faced by women who pursued academic careers.

“I really wish people wouldn’t think about that aspect so much,” she said. “Nothing comes along from becoming a full professor – it’s not a promotion as far as I can see.”

Dr Strickland added: “I think people are reading into it because I’m a woman but the fact is I just never applied,” she said. “I couldn’t see the point. Every time [the role] came up, they flagged it to me, but I’d say, ‘why should I go to all that work when I don’t even know what I’d get for it?’”

Dr Strickland’s award – which she shares with her research partner Gérard Mourou, professor emeritus at the University of Michigan, and Arthur Ashkin, formerly of Bell Laboratories – comes in the wake of a public row about the role of women in physics involving a senior scientist at Cern.

Alessandro Strumia, a professor from Pisa University, was barred from working with the European nuclear research centre after telling an event that “physics was invented and built by men, it’s not by invitation”.

Dr Strickland told THE that she thought Professor Strumia was simply a “sad person, an outlier” who did not represent the vast majority of male scientists.

“Obviously the conversation [about women succeeding in science] has to keep happening, to keep making things move forward, but I’m not frustrated,” she explained. “I’m not someone who believes we have not made progress.”

Dr Strickland added that she was “worried” that the focus on her gender was “taking away from the two men that won, because obviously it’s a great accomplishment for them too”.

Dr Strickland was not even the subject of a Wikipedia page prior to her win, but said that the attention had been “non-stop” after she received the call from the Nobel committee on 2 October. “Even just walking through campus and being photographed, I thought – rock stars do this every day. I’m like a rock star, what a strange feeling,” she said.

Despite putting a lot of focus on her as an individual and some “funny” comments about her physical appearance, attention was no bad thing, she conceded, “because this is such a huge deal all of a sudden all people around the world are paying attention to science”.

“I don’t think science goes into the mainstream media as much as entertainment or politics, so it’s good to keep reminding people that we are out there in the labs, doing great things,” Dr Strickland said.

This year’s laureates also included Frances Arnold, professor of chemical engineering, bioengineering and biochemistry at the California Institute of Technology, who became the fifth woman to win the chemistry prize.

Dr Strickland said: “The message is loud and clear: women can do whatever they want.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login