Australian scholars have welcomed the government’s pledge of A$1.9 billion (£1.1 billion) to secure the future of the country’s major research facilities, but have expressed concern that the vast bulk of the money will not be seen until well into the next decade.

The launch of the 10-year research infrastructure investment plan follows years of stop-start funding for several dozen research and access networks, an Antarctic agency, telescopes, research vessels, supercomputers, a nuclear reactor, biological collections, a biocontainment laboratory, particle accelerators and other high-end technology.

It also comes after a 2015 promise of A$1.5 billion over 10 years to support the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy, or NCRIS, with a further A$520 million for a football-field sized particle accelerator called the Australian Synchrotron. In addition, the government last year pledged more than A$500 million to upgrade two supercomputers, boost satellite positioning technology and give Australian astronomers access to telescopes in Chile.

But the road ahead is bumpy. A windfall of A$199 million, to be allocated by the end of June, will be followed by commitments of just A$6 million in the next financial year, A$26 million the year after that, A$76 million in 2020-21 and A$87 million in 2021-22.

The vast bulk of the money – about A$1.6 billion – will be allocated after mid-2022, beyond the scope of the budget’s forward estimates.

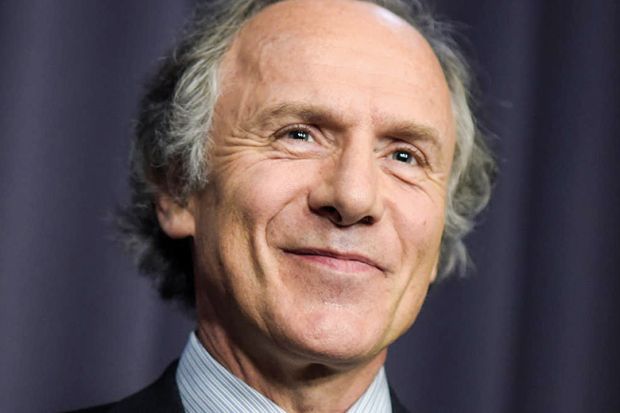

Alan Finkel, Australia’s chief scientist, conceded that the funding was “lumpy”, with many details still to be specified. “But I’d rather be dealing with the lumpiness in a committed A$2.4 billion than dealing with not having any money at all,” he told Times Higher Education.

Dr Finkel said that major research infrastructure could now anticipate average income of A$400 million a year, a far cry from the situation before 2015, when administrators did not know whether they would be funded from one year to the next.

But shadow science minister Kim Carr said that the newly announced money was far from certain, with most of it backloaded until as far away as 2029. “That’s some elections away. Given the electoral cycles in this country, it could be four or five elections away,” he said.

Dr Finkel said that while the NCRIS commitment had been similarly long-term, the promised money had been delivered so far.

“Is it likely that five, six or seven years from now, a new government will come along and cancel it all? I don’t think so, because they’d have to cancel a well-considered investment plan,” he said.

However, Mr Carr said that a Labor government would reserve the right to change the plan, adding: “The humanities, for instance, have been completely excluded.”

Mr Carr pointed out that the government was slashing two other big research funding programmes: the research and development tax incentive, which has been tightened up to the tune of A$2.4 billion, and the A$3.8 billion Education Investment Fund, which the government has long planned to abolish.

While university and science groups are upset at the loss of the EIF, they have been upbeat about the newly announced funding. Commentators have welcomed investments into the use of information technology in research, and an allocation enabling the flagship research vessel Investigator – which has spent much time tied up at its Hobart dock – to operate for an extra 120 days a year.

On the other hand, just A$400,000 of a planned A$76 million in biosecurity spending will be allocated by mid-2022.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login