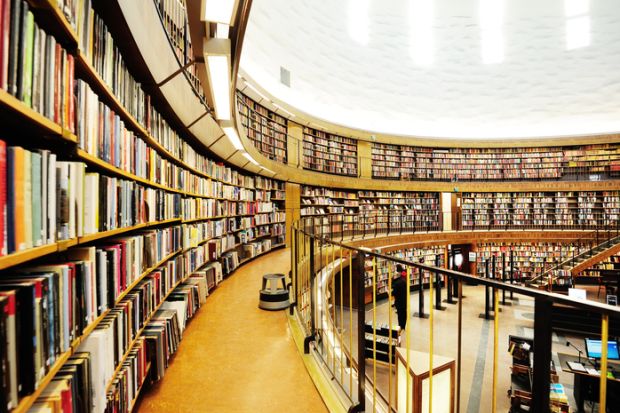

There is a fairly standard image of the university library. At least in affluent Western countries, they are generally open long hours, run by professionals with their own acquisitions budgets, and fairly comprehensive in their coverage of major disciplines. And, until recently, they have been notable for a solemn silence.

Yet much of this model is relatively new and now coming under pressure. A recently published book, The Library: A Fragile History (Profile), offers some striking insights into the past and future of university libraries. Its authors are Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen, the founding director and deputy director of the Universal Short Title Catalogue, the leading resource for the study of early printed books, at the University of St Andrews, where they are also, respectively, professor of modern history and British Academy postdoctoral fellow.

The book describes, for example, how Sir Thomas Bodley, in 1598, “offered to restore the dilapidated [Oxford] university library, entirely at his own cost”. Since his own considerable wealth was “padded by the fortunes of a wealthy Devon widow who had succumbed to his charms”, he was able to provide an acquisitions budget. He was a pioneer in insisting on silence and prohibited the lending out of books, a rule upheld even when King Charles I and Oliver Cromwell asked to borrow some.

Yet “the Bodleian was very much an exception”, Professor Pettegree told Times Higher Education, “not least in that Bodley was able to leave an acquisitions budget. Virtually no other university library did until the 19th century. They were entirely dependent on donations, usually when people retired or died, and sometimes buying other books by selling duplicates. That meant that libraries were always inheriting the taste of a previous generation.”

Libraries always face challenges about exactly what to collect. Bodley banned “idle books and riffe raffes”, meaning texts in English rather than Latin. This even led to the sale of a famous First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, which then had to be bought back at vast expense. Later chief librarians at the Bodleian regretted the decision not to access women’s magazines in the 1920s, now widely regarded as an important source for social history. And university libraries still had little idea, Professor Pettegree pointed out, “how to curate the everyday commerce of information through email, Twitter and Instagram”.

The 19th century witnessed both a significant expansion of universities and the development of librarianship as a profession. Prior to that, Professor Pettegree explained, “libraries would only let in students for four hours a week, if that, and the librarian didn’t have a staff”. Today, of course, many university libraries are open 24 hours a day, particularly in places with lots of American students, since “24-hour opening is regarded in the US as part of the basic fabric of university life”.

This was just one aspect of the way that university libraries were showing “an increasing sensitivity to student concerns and student needs” – partly driven in the UK by the need for institutions to score well in the National Student Survey – although this meant that “few libraries also have the resources to keep on top of all the research areas of their staff”.

With regard to the widespread shift to digital collections, Professor Pettegree warned about “the dangers of embracing new technologies before they are properly stress-tested. As early as the 1930s, people were talking about the death of the book. Microfilm was going to replace it and make books redundant. But in fact it is microfilm which is now mostly redundant. Having filmed and then destroyed newspaper collections, you are left with neither resource.”

While e-books had obvious advantages, Professor Pettegree continued, “you are taking a big bet that the technologies we rely on are going to be continuously available in the future. The biggest question is whether computer security systems can keep ahead of the bad guys.” He therefore welcomed the national agreement to retain three hard copies of all periodicals, even after their contents had been digitised and made freely available.

Today’s university libraries were “turning over more and more of their floor space to interactive learning and coffee shops” and were therefore much noisier than in the past, yet Professor Pettegree reminded outraged traditionalists that this represented “a return to the Renaissance ideal of the library as a place of conversation rather more than reading”.

He also had one final piece of advice for university leaders: “Readers in libraries are much more interested in texts and access to information than they are in architecture. The major building projects many universities embark on as a form of prestige, which often give much more space to the atrium than book storage, are very much a mixed blessing.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login