Many working in universities describe international higher education as a public good rather than an income generator. But shrinking higher education budgets on a national level and shifting demographics in many European countries mean that, in reality, financial gain is often the main factor universities consider when they prioritise international activities.

The European Association for International Education’s Barometer: Money Matters surveyed more than 2,300 international education professionals working in higher education institutions around Europe. Just over half of respondents (53 per cent) said that student recruitment – one of the biggest income generators for universities – was a prioritised activity in their institution’s internationalisation strategy. This was second only to the international mobility of home students, listed as a priority by 68 per cent of surveyed practitioners, according to the report by the EAIE – which holds its annual conference, in Helsinki, between 24 and 27 September.

An additional one-third of respondents said “programmes in non-local language” were also a top-five priority, reflecting the growing trend among non-English-speaking countries to develop English-taught programmes in order to attract international students.

Country-level responses for the nine European Higher Education Area countries featured in the report tell the complex story of current funding policies and demand for higher education around Europe, and how these influence international strategies at individual institutions.

For example, student recruitment was mentioned as a top-five priority by a whopping 85 per cent of respondents in the UK, compared with just 36 per cent of those at German universities.

In the report, authors Laura Rumbley and Anna-Malin Sandström write: “The UK may offer the most clear-cut example of how tuition fee challenges and opportunities can serve as a driving force for internationalisation among the nine countries highlighted in this report.” They cite the imposition of full tuition fees on international students in the UK as helping to “establish the framework conditions for a reliance on, or interest in, this population”.

Transnational education, another potential income generator, did not surface as a priority among respondents across Europe, but branch campuses and other TNE activities were rated by more than a quarter of UK respondents as a top priority.

Meanwhile, 61 per cent of UK respondents said “national legal barriers” are a top 10 external challenge to internationalisation, compared with just 17 per cent of Dutch respondents, 15 per cent of German respondents and 27 per cent of respondents from the EHEA overall.

Whether or not concerns about Brexit would be reflected in this response is unclear, Dr Rumbley, associate director of knowledge development and research at the EAIE, told Times Higher Education. “It may be easier to make the case, though, that visa and immigration policy affecting incoming international students might have been more top of mind,” she added.

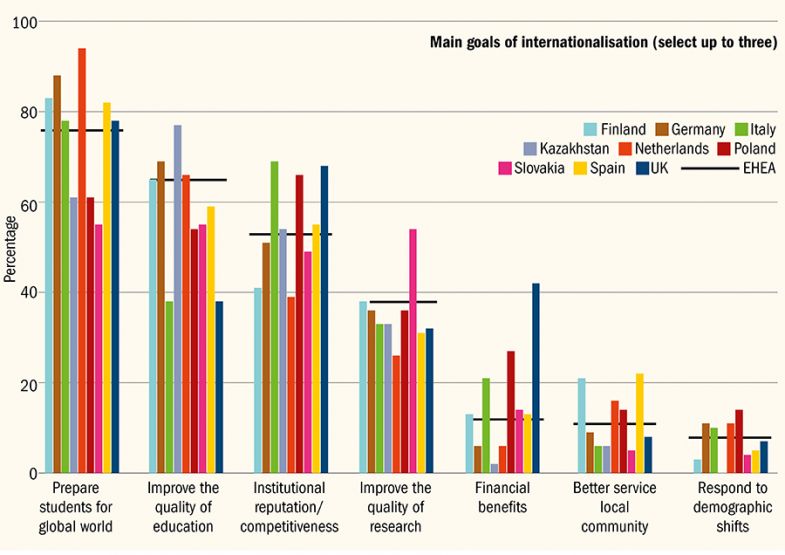

The rationales behind internationalisation strategies

When surveyed on the main goals of internationalisation, 42 per cent of UK respondents listed “financial benefits” among their top three, compared with just 12 per cent of survey respondents overall.

Khawla Badwan, a senior lecturer in teaching English to speakers of other languages and applied linguistics at Manchester Metropolitan University, said it was not surprising that the UK stands out among European institutions for being motivated by the financial gains of internationalisation.

“Universities in the UK – like many American and Australian universities – have witnessed a tremendous shift in their role since the 20th century. Universities, nowadays, are acting as enterprises that produce scholars and employable individuals,” she said.

According to Dr Badwan, two key reasons for this shift are the rise of knowledge economies and decreased government funding for universities in the UK.

“In response to these dramatic changes, universities are left with no options but to compete to recruit students and to receive external research grants,” she continued.

“It is fair to say that universities did not probably choose to be profit-driven commercial enterprises. Rather, they are forced, under contemporary global conditions and financial pressures, to act in this capacity to stay economically sustainable.

“International student recruitment is, of course, at the heart of this dilemma given that international students pay higher fees which are increasing annually.”

Among the pitfalls of being commercially driven in internationalisation efforts is the “tension” between marketing and giving students sufficient information, said Dr Badwan, who carried out a study in 2017 looking into the impact that universities’ recruitment strategies have on international students’ expectations of their academic and social experiences.

“There are striking similarities between the online marketing discourses adopted by different universities, to the extent that it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to identify these universities based on their marketing discourses,” she said.

“This is because the online presence of universities tends to be framed around the creation of a ‘brand’, with a lesser focus on the detail of what to expect regarding academic life in the UK (styles of delivery, modes of assessment, support mechanisms, relationship with tutors, etc).”

What is more, Dr Badwan noted, the international students who took part in the project “reported that they were not as interested in reading about what universities say about themselves, as they were more concerned with the practical elements of their course”.

After the UK, respondents to the EAIE survey from Italy and Poland stand out for their focus on income-generating activities. Among Polish university representatives, 72 per cent said student recruitment is a top-five priority, while 59 per cent cited creating programmes in a foreign language.

Meanwhile, 68 per cent of Italian respondents cited international student recruitment as a priority and 55 per cent said non-local language programmes are a priority.

In addition, 27 per cent of Polish respondents and 21 per cent of Italian respondents said “financial benefits” are one of the top three goals of internationalisation at their institution – compared with 13 per cent in Spain and 2 per cent in Kazakhstan.

In the case of Poland, the ability of universities to establish their own fees for non-EU or European Free Trade Association students may partly explain this focus, the report says.

However, in Italy, where tuition fees for both EU and non-EU students are similar, domestic population decline could be a contributing factor – even though just 10 per cent of respondents indicated that reacting to demographic shifts was a main goal for internationalisation, the report notes.

Compensating for a lower number of 18-year-olds is a “side result” of internationalisation in Italy, according to Davide Donina, a higher education researcher who is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Bergamo. “Overall now there is a decline, but in the next 10 years the birth rate is quite…steady.”

The emphasis on income-generating activities is likely due to a greater need to make financial gains on the back of cuts to higher education budgets, he said, even though there are only about 90,000 international students at Italian institutions, who pay similar fees to domestic students.

“Even this small amount of money [from foreign tuition fees] is important in such an underfunded higher education system as the Italian one,” he added.

Indeed, Italian respondents were more likely to cite a “lack of national support or strategy” as a top-10 external challenge to internationalisation – with 59 per cent of respondents doing so – than any other surveyed country. Spanish respondents were the second highest with 35 per cent.

According to Dr Donina, internationalisation in Italy is still in the “initial phases”. He added: “In this moment, internationalisation is more a mimicking process of what’s happening in other countries because everybody considers it important, but from a policy perspective it’s not so well developed in Italy yet.”

The EAIE report concludes that “money matters do not stand out as major drivers for internationalisation across the EHEA as a whole”, but concedes that “it is possible that many respondents might have opted for ‘socially desirable’ responses to the Barometer survey”.

Dr Rumbley said that old sensibilities of public education in Europe might have influenced respondents’ answers.

“The idea that internationalisation might be leveraged for financial gain seems to sit uncomfortably,” she said. “So, when asked for what reasons their institutions are internationalising, Barometer respondents – even when financial benefit might be a relevant point – could have felt compelled to fall back on more familiar and culturally ‘comfortable’ non-financial rationale.”

Increasingly, however, Dr Rumbley said that international educators are becoming more comfortable with the idea of talking about higher education as both a social good and something bound to financial realities.

“No service to society in this world can be understood as truly ‘free’, but at the same time not everything that generates revenue is ‘greedy’,” she argued. “I think that thoughtful higher education stakeholders and policymakers can find ways to strike a healthy balance between these two positions.”

Finding such a balance could be a pressing issue as public university funding across Europe stumbles along, decreasing in some countries and stagnating in others, while at the same time enrolments rise.

Could the UK’s financially motivated approach to internationalisation be a model for other systems if they find themselves in a similar position of funding cuts?

“It’s not out of the question that we might see some adjustments in approach in response to shifting financial realities,” said Dr Rumbley. “As we mention in the Money Matters report, mutual learning across national systems and experiences may be very useful in this area.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Striking a balance be tween cash and public good

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login