UK universities have been warned not to create a new “over-reliance” on one source country for international students after new data suggested India was set to overtake China as the biggest source of new entrants.

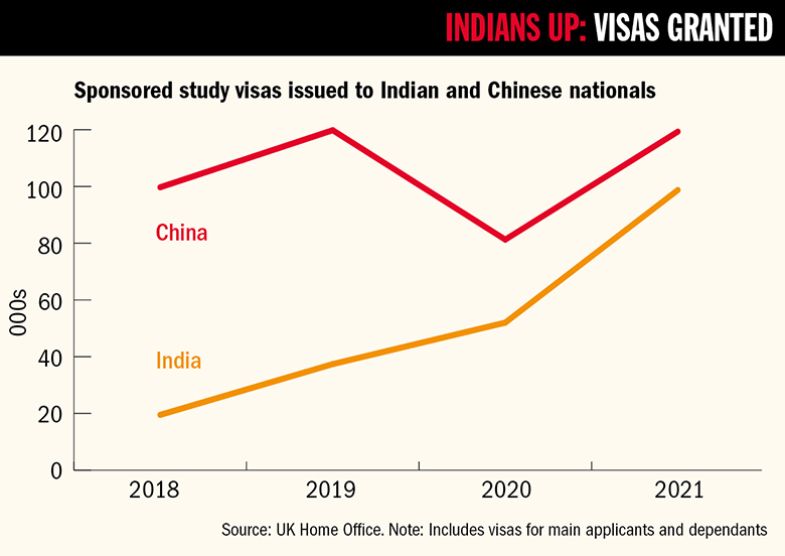

Latest figures from the Home Office show that almost 100,000 study visas were issued to Indian nationals last year, nearly double the year before and only about 20,000 fewer than those granted to Chinese citizens.

Study visas granted to Indian nationals were just 8 per cent of the total in 2018, as opposed to 23 per cent last year, while China’s share fell from 42 per cent in 2019 to 28 per cent in 2021.

Although visas may not directly translate to enrolments, the data suggest that the UK is well on track to smash a goal put forward in a report led by former universities minister Lord Johnson of Marylebone for 100,000 students from India to be studying in the country by 2025: official figures show that there were already around 85,000 Indians studying at UK institutions in 2020-21, most of whom would have obtained visas before 2021.

However, Lord Johnson told Times Higher Education that while he welcomed the rapid growth in demand from India “the sector needs to continue to seek to achieve a broad-based diversification in international recruitment”.

“There is an obvious danger in simply replacing dependence on China with over-reliance on India,” he added.

The growth in students from India – which probably reflects a number of factors including the reintroduction of post-study work visas, a deliberate UK government strategy to target the Indian market and the change in student flows because of the pandemic – is likely to have a major effect on the shape of UK higher education too, experts said.

Janet Ilieva, founder of international mobility research consultancy Education Insight, said that much of the growth in global demand for courses in the UK was coming from countries like India, whose students were most interested in one-year taught master’s.

“Continued growth from these countries is likely to shape the UK mainly as a postgraduate study destination,” she said.

At the same time, a fall in the number of new students from China – the number of Chinese entrants to UK universities fell 5 per cent in 2020-21 – coupled with the slump in European Union demand “will have a significant negative impact on undergraduate enrolments in the UK”.

She also pointed out that China was “the largest source country for PhD students”. Data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency show that in 2020-21 Chinese postgraduate research students at UK universities outnumbered those from India by about five to one.

“If declines are to affect the demand from China for doctoral degrees, then STEM areas are likely to suffer the most,” Ms Ilieva said.

Such observations were also backed up by Home Office data on the types of universities that are seeing a surge in visa applications.

In the past, research-intensive universities such as those from the Russell Group have tended to sponsor a large proportion of visa applications when most were coming from China. But in the latest data, non-Russell Group institutions accounted for three-quarters of the increase in Certificates of Acceptance for Study (CAS) being used in applications, compared with 2019.

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, said that student flows out of China and India and into the UK “have different drivers” and so the “surge” in the demand for master’s courses from India was “distinct” from the patterns for China and PhDs.

However, he said he still thought the flow of Chinese postgraduate researchers was “likely to trend downwards in the longer term” because of the geopolitical tension in recent years between the US and China “and its echo” in the UK.

“If that happens, on top of the loss of doctoral and postdoctoral talent from Europe due to Brexit” and the doubts over Horizon Europe participation, “this starts to look like a serious problem”.

“Where do the top-drawer doctoral and postdoctoral people come from in future?” he added.

Professor Marginson also said that the war in Ukraine was likely to have huge ramifications for geopolitics, and therefore on student and researcher behaviour and activity, “but it is too early to call all the longer-term impacts and knock-on effects”.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: India set to overtake China as foreign student source

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login