In the Hollywood film Good Will Hunting (1997), Matt Damon plays a janitor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who is smarter than the mathematics professors he cleans up after.

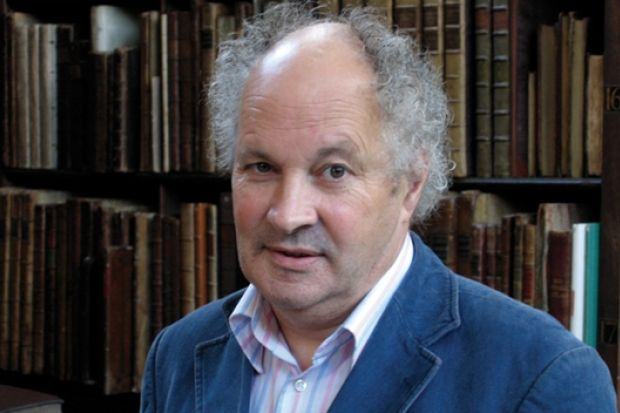

Arthur Gibson, resident academic at the University of Cambridge's department of pure mathematics and mathematical statistics, may not look like Damon's troubled maths genius Will Hunting, but their routes into academia are uncannily similar.

Gibson's true-life story may even be more extraordinary than the one scripted by Damon and co-star Ben Affleck for the Oscar-winning film.

In the movie, Hunting's intellect is revealed when a professor chances upon him solving a fiendishly difficult maths equation aimed at graduate students.

In Gibson's case, the moment of discovery took place while he was working as a librarian's assistant at the University of Leeds almost 40 years ago, having dropped out of school at the age of 14 with no qualifications.

"Some chap came to return some books and I asked him what he thought of one of them," he recalls. "We chatted and he said I had some interesting thoughts on one of the paragraphs, so I asked him what he thought of the following one.

"He said he hadn't read it that closely, so I recited some of it. He thought this was a trick, so he...brought some other people over to listen to me."

What the curious academic had realised was that Gibson had a photographic memory and was able to recall verbatim long tracts of text.

"It's [a skill] I've always had," he says. "When I later gave lectures, I would never use notes. I would reel off the quotes and references without a problem."

Word of his talent spread around Leeds and he was asked to take a number of IQ tests, registering an unusually high score of 210.

But, like Hunting, Gibson had serious emotional problems stemming from a traumatic childhood, which, allied with chronic dyslexia, frustrated his academic ambitions.

Growing up in a Bradford slum, he was regularly beaten by his alcoholic father, a former boxer and Dunkirk veteran who took out his frustrations on his wife and children.

"He was a dreadful man sober and even worse drunk. And he was drunk twice a day," Gibson says. "Like me, he had a photographic memory, but he was frustrated because he couldn't make sense of [the] information.

"He was a bookie's runner and could do all the sums in his head. One day, he took me along to the pub with his friends and asked me to have a stab at the maths.

"I got one or two wrong and when we got home, he asked me to put my hands on his chest. He then took his cigarette and burned it into the back of my hand - he said I'd made him look bad."

Anxious to leave his unhappy home, Gibson married at the age of 19 and soon had four children to support. He gained work designing window displays for shops or doing casual labour before landing the job at Leeds.

But although his vast potential had been spotted by academics, when confronted with the university's entrance examination for mature students, he froze.

"I just wrote wavy lines," he explains. "I can still see the words that I thought I'd written, but I was told it was nothing but lines."

Although Gibson was unable to enter Leeds, Peter Geach, professor of philosophy at Leeds, offered to tutor him privately. Geach, whose wife Elizabeth Anscombe was a philosophy professor at Cambridge, arranged for Gibson to be interviewed at the ancient university.

He was accepted at Jesus College, Cambridge to study Oriental languages at the age of , where he continued his friendship with the couple, even sitting his finals at their family home to overcome his extreme fear of exams.

"I have no memory of it, but I was later told by one of their sons that I'd thrown up over their sofa and blacked out," he said.

Despite this, he passed his exams at the age of 30 and headed to the University of Manchester with his family. There he studied for a PhD in philosophy and honed an unorthodox interdisciplinary style.

Works by Gibson have included reflections upon astronomy, theology, cosmology and logic - exploring how the disagreements between disciplines raise questions about fundamental points of knowledge.

The late, great Shakespearean scholar Sir Frank Kermode once exclaimed: "Arthur Gibson is either a madman or a genius - and I don't think he's mad."

After working for various Oxbridge colleges, Gibson joined the philosophy department at the University of Roehampton and became professor and chair.

He retired two years ago, but has now resumed academic life at his alma mater. He has been invited by Trinity College Cambridge to edit a long-lost collection of papers by Ludwig Wittgenstein dictated to his student Francis Skinner.

Gibson also started this year as academic-in-residence at the maths department, where he is working on a combination of cosmology, pure maths and philosophy.

"I retired at 65, but I feel I am just getting going," he says.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login