It seems a lifetime ago, but it has been just a matter of weeks since the UK’s chancellor, Rishi Sunak, gave his first Budget, announcing a huge uplift in the money being pledged for research.

It was a widely welcomed move that has the potential to catapult the UK from a laggard among developed nations in terms of investment in research and development to the world’s top tier.

But could the speed with which the coronavirus crisis is engulfing Europe and North America already be casting doubt on the ability of the UK, and other countries, to maintain such levels of ambition for research spending?

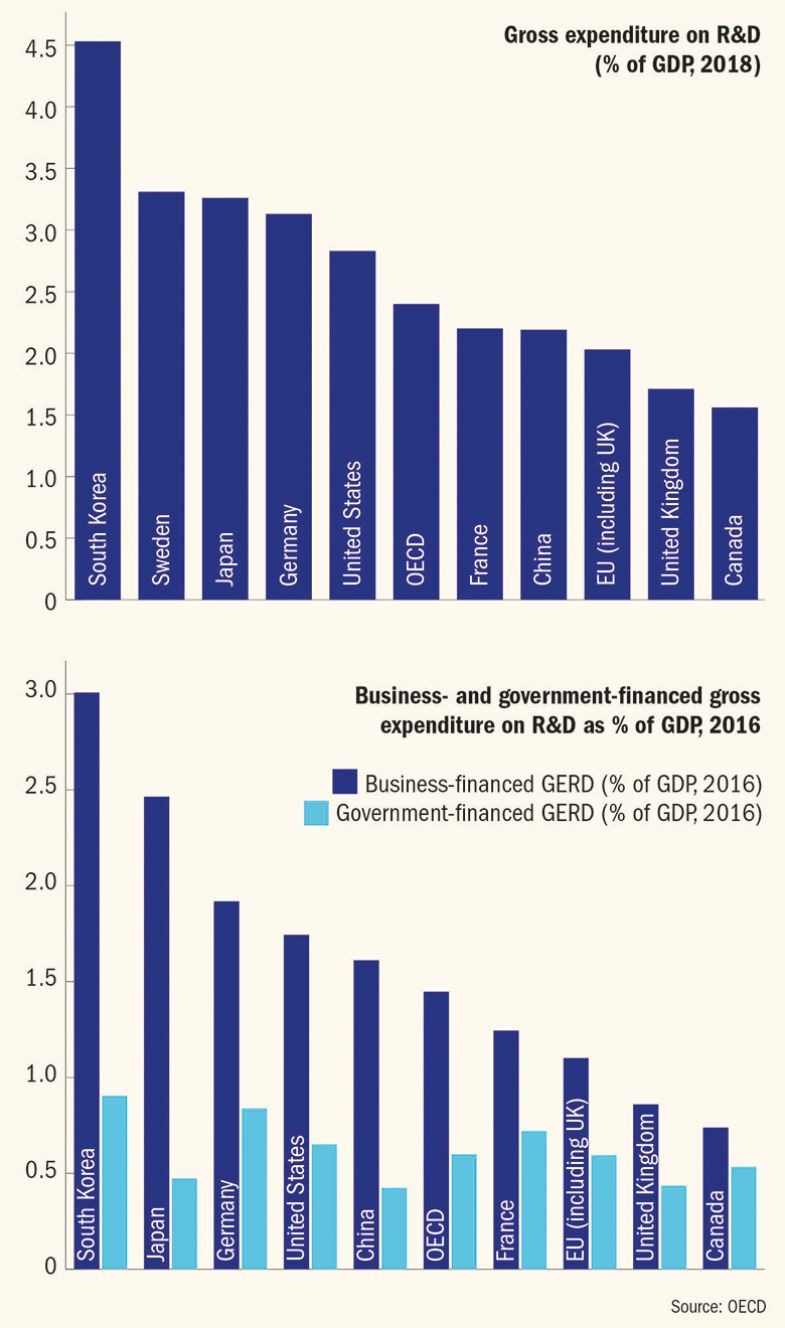

Figures from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development give a flavour of how the UK’s planned boost would have changed the landscape in the absence of any disruption from the pandemic.

In 2018, according to the OECD statistics, the UK’s gross expenditure on research and development (GERD) − which includes spending by businesses, non-profits and others − was 1.71 per cent of GDP, well below the group’s average of 2.4 per cent (which is the UK government’s eventual target) and the European Union’s 2 per cent. Meanwhile, well ahead of these averages were countries including South Korea (4.5 per cent), Sweden (3.3 per cent), Germany (3.1 per cent) and the US (2.8 per cent).

Public and private research spending before the pandemic

The UK’s Budget pledge to boost public expenditure on research to £22 billion by 2024-25 looked set to radically alter its position.

According to the documents from the Budget, such a figure would push government expenditure on research to 0.8 per cent of GDP (latest OECD data, for 2016, show the UK was at about 0.4 per cent), “placing the UK among the top quarter of OECD nations – ahead of the USA, Japan, France and China” in terms of government investment.

It could quite conceivably also push the country beyond the 2.4 per cent marker for overall research spending, although this would very much depend on how the government’s boost leverages investment from elsewhere, particularly the private sector.

For instance, nations such as the US, Germany and South Korea have their already higher public investment topped up significantly by the private sector. In 2016 (the latest year with comprehensive data), business-financed GERD was 3 per cent of GDP in South Korea, 1.9 per cent in Germany and 1.7 per cent in the US. Meanwhile, in the UK it was 0.9 per cent.

Projections from the UK’s Campaign for Science and Engineering (CaSE) suggest that even with the previous Conservative election manifesto pledge to increase research spending to £18 billion, an additional £6 billion in private spending would have been leveraged by 2024-25. Therefore, the government’s latest announcement that it was aiming for £22 billion rather than £18 billion could be so transformative that the UK easily exceeds 2.4 per cent overall, and well before the original plan to do this by 2027.

Sarah Main, CaSE executive director, said that this was partly because the planned uplift sent a major signal to private companies.

When deciding whether to invest, “research-intensive companies large and small are looking…for the strength of the science base, the quality of the talent pool, but they’re also looking for the intentions of government”, she said. “These kinds of long-term, forward-thinking, bold plans…are a really powerful signal.”

However, this is where concerns about the Covid-19 outbreak and its effect on economies across the globe start to look like a major caveat, both in terms of government spending and private investment.

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, said there was a “real danger” that the crisis could completely change the environment around the UK’s plans and those of other countries too.

“The [UK] government is running up a large deficit on expected spending to cover wages, business costs and the unprecedented demands on the health system. In addition, the economic recession triggered by the pandemic will be very severe,” he said.

Caroline Wagner, Milton and Roslyn Wolf chair in international affairs at Ohio State University, said that a global economic downturn might not affect public spending on R&D too much, because “governments often add funds to R&D budgets in times of recession” but the “opposite is true for the private sector”.

“Public policy can respond to the pressures on the private sector by increasing R&D tax credits and possibly expanding tech procurement. These actions are often considered by policymakers in times of downturns, so I expect they will arise again in the scientifically advanced countries,” Professor Wagner added, although she stressed that taking action quickly would be important.

In terms of the UK, Dr Main said it was clear that when details of research spending plans are actually thrashed out for the government's planned spending review, the country will be “in a very different societal and fiscal environment”.

But she thought that the “principles and the issues will remain the same” with regard to research.

“It will remain the same that this government – and I personally believe from [looking at their] manifesto commitments, many of the other parties as well – believe in the power of research and innovation investment to deliver for individual prosperity and for national productivity and for some of the big global challenges we seek to address.”

Another silver lining for research amid such dire economic forecasts may be that its “vital importance” is being “underlined by this crisis”, Professor Marginson said.

“The crisis reminds everyone what a great humanist institution modern medicine is,” he added. “People understand that medicine depends on scientific research, and epidemic diseases are brought under control only when research establishes a vaccine,” he said, adding that the crisis would “isolate and weaken” anti-science messages such as the “nutter fringe opposition to vaccination”.

Professor Wagner also said the pandemic had “revealed the core contributions of science to medicine and health, and this fact is likely to increase support for science funding”. This made it a “good time to push for changes” around the world to “encourage legislatures to provide longer-term R&D funding commitments”.

And she added that the crisis could also “spur an increase in funding for medical and health sciences in Asia”, where there was currently more of a slant towards physical sciences, especially in China.

The potential effect for transformational science on a global level was “actually really exciting and presents a wonderful opportunity to speed basic science into practical applications much more quickly”.

However, Professor Marginson urged slight caution with regard to a changed long-term focus for research in countries such as China. “After the crisis, research priorities – including the cultural differences between countries – are just as likely to revert to previous patterns. There’s a good deal of path dependency and inertia in the organisation of research.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: How could the coronavirus crisis affect global science investment?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login