Deepening multimillion-pound deficits at a number of English universities have prompted warnings about the “sustainability” of institutions in a market-based system and a potential worsening of regional inequality if towns and cities reliant on universities see reduced investment.

Sector sources report concerns about the financial health of some institutions and suggest that a number of universities that saw deep falls in student recruitment in recent years may have continued that trend this year.

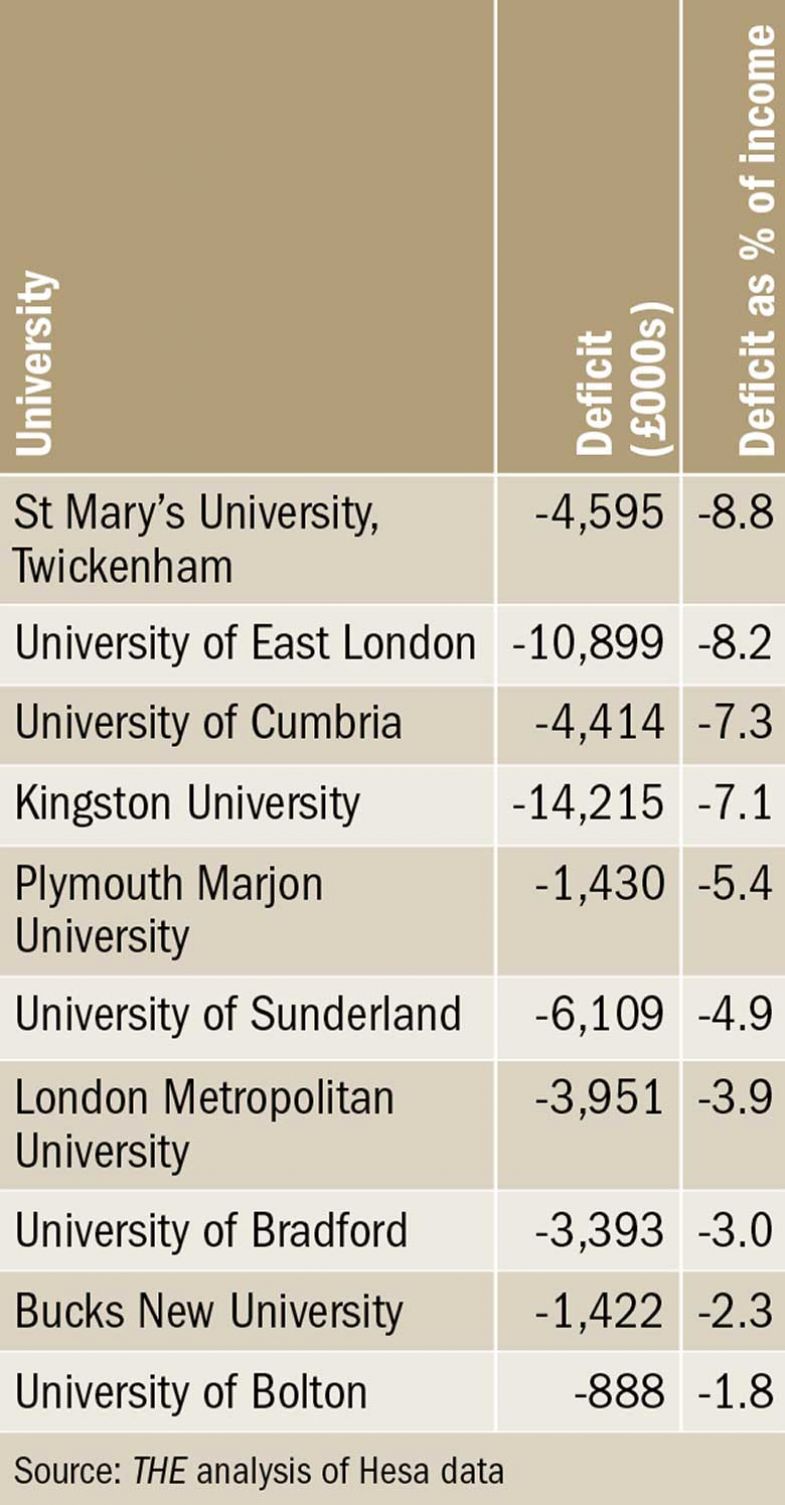

Times Higher Education analysis of English universities’ finances in 2016-17 shows that deficits at individual universities ran as high as £14 million, and up to nearly 9 per cent of total income.

In total, 19 English universities returned deficits that year, up from seven the previous year.

Of the 10 large English universities with the biggest deficits as a proportion of total income last year, six also figure in the top 10 institutions seeing the biggest falls in recruitment between 2010 and 2017. Student number controls began to be lifted in 2012, before a fully unrestricted market in student recruitment was introduced by then chancellor George Osborne in 2015.

The fierce competition for students created by that policy was cited as a factor by some of the institutions with the largest deficits; Ucas data has shown that the least selective universities have lost out in the domestic recruitment race to more prestigious rivals in recent years. But actuarial changes adding to pension costs and the spending on transformation programmes needed to turn institutions around were also cited.

The University of East London returned a deficit of £10.9 million in 2016-17, after a deficit of £6.8 million the previous year. A spokesman said that “a complex set of interrelated issues such as pension increases, the changing UK demographic profile, [and] a hostile immigration policy…require the higher education sector as a whole to…take measures to ensure the sustainability of its institutions now and for future generations”.

He added that UEL was “not a higher risk institution” and was “confident about our future and irreplaceable role in driving social mobility”, a confidence “reflected in both our 2017-18 performance and our medium-term financial forecast”.

The University of Bradford, whose vice-chancellor Brian Cantor recently announced that he would step down at the end of this academic year, citing “difficult external circumstances” that had hampered expansion, returned a deficit of £3.4 million in 2016-17, after a deficit of £1.9 million the previous year.

A spokeswoman said that the higher education sector had become “increasingly competitive” but added that the university was “on track” to “consolidate in respect of recruitment from the UK, and build on our strengths in overseas markets”.

England: biggest deficits

Several London-based post-92 institutions are among those with the largest deficits. Other universities are in regional towns and cities with high levels of deprivation, while many of the capital’s universities serve areas with major social challenges.

Alan Palmer, head of policy and research at MillionPlus, the association of modern universities, said that while there has “always been competition” in the sector, “the introduction of specific policies by government since 2010, such as the removal of the student number control, has clearly contributed to higher levels of segmentation between providers”.

“The concern is that this reinforces existing hierarchies, prejudices and perceptions about higher education providers rather than a proper understanding of the individual and diverse strengths of universities,” he added.

Mr Palmer continued: “This approach is certainly not in the interest of students or communities where these universities are anchor institutions. These institutions, usually modern universities, offer high-quality, locally based, employer-relevant provision that creates opportunities for people to study conveniently, including those for whom mature study or learning while working is the only viable option.”

Andy Westwood, professor of government practice at the University of Manchester, highlighted the fact that “some of the universities suffering most – in recruitment or financial health – from the higher education market” are located “among the ‘left behind’ communities exposed by the Brexit vote”.

He added that, in higher education policy, the Department for Education, the Office for Students and UK Research and Innovation “don’t think in geographical terms or about the geopolitical consequences of the Brexit vote”.

Professor Westwood said that “in a weak local economy you’re going to depend on big public institutions such as universities and colleges acting as anchor institutions much more than in better-off communities. But all the economic challenges are likely to make it harder for these institutions to compete in national market-based systems – harder to recruit students and staff, harder to get research income and so on.

“As a result they get smaller, close departments and campuses and the economic gaps between them and larger, more successful cities – and their institutions – just get wider and wider.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: University deficits increase as students flock to elites

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login