Until a couple of weeks ago, universities around the world might still have been focusing their assessments of the potential fallout from the coronavirus outbreak on student recruitment from China.

However, as the outbreak spreads across the world and the virus becomes endemic in more countries, global higher education might start to wonder if the dent to international recruitment will similarly pay no heed to borders.

If this is the case, what could be the potential financial consequences of a general drop-off in recruitment, however temporary?

The latest figures from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) suggest that about 5.3 million students were enrolled outside their home country in 2017, with more than a quarter of those from East Asia and the Pacific region.

Leaving aside for one moment those who are in the middle of a course and might be hit by travel restrictions, how could total outbound mobility be affected by people cancelling or delaying plans to start a course abroad?

According to Anna Esaki-Smith, co-founder and managing director of the research consultancy Education Rethink, the world has entered “uncharted territory” with Covid-19. However, the impact of SARS, although much smaller, was a “historically relevant” example.

“From a data perspective, we can estimate that if [the Covid-19 outbreak] behaves exactly like SARS, there would be an 8.4 per cent total drop in Chinese outbound students over the next two years, meaning until the end of 2021,” she said.

Taking such a figure and applying it to international students across all countries, using Unesco data for 2017, would mean some 80,000 fewer inbound students in the US, about 35,000 in the UK and roughly 30,000 in Australia.

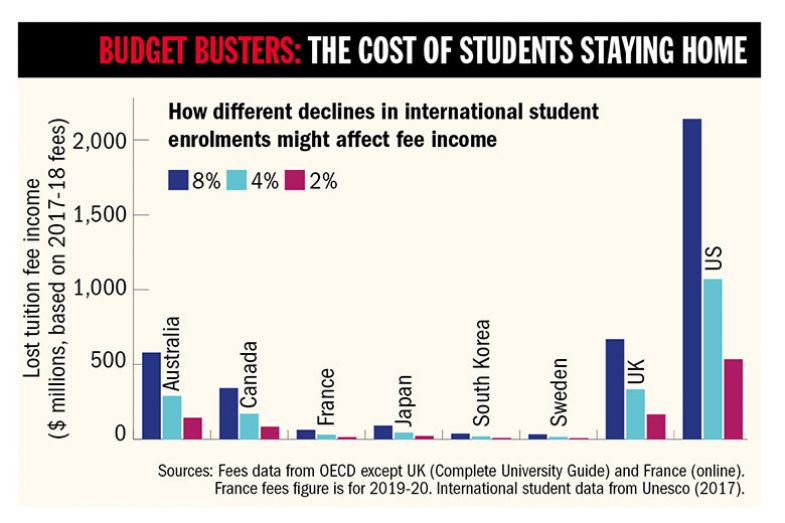

Factoring in figures for average overseas undergraduate fees from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and other sources suggests that such falls in traffic could lead to a drop in fee income of about $3.5 billion (£2.7 billion) for these countries alone.

Such figures may be far from what really might happen: they take no account of the actual complexities of overseas fee levels in different countries; assume that annual undergraduate fees are a good guide for all tuition charges; and presume that the drop is not more prolonged.

Countries other than the US, the UK and Australia – which have among some of the highest fees for overseas students – might not be hit quite as hard in terms of income, either.

A combination of smaller international student cohorts and lower fees would mean that even an 8 per cent drop in enrolments would result in an overall loss in fee income of less than $100 million in Japan and under $50 million in South Korea.

But the figures illustrate how a major change in demand for overseas study could affect universities financially. And even if international student numbers fall by more like 2 per cent, this would still represent $500 million in lost fee income in the US and hundreds of millions elsewhere.

And this is all before counting the knock-on effects for economies of any extra spending by international students in their host country, including on accommodation, food and leisure activities.

For instance, local estimates of the total financial impact of Australia’s travel ban – which has prevented thousands of Chinese students from beginning courses in the country – suggest that it could be as high as $5 billion, Ms Esaki-Smith said.

She added that with the current outbreak, a crunch point was fast approaching where international students scheduled to start courses in the autumn would be forced to make decisions about their plans.

“If travel bans continue, will these students be willing to maintain a wait-and-see approach when it comes to investing in an overseas education?” she said.

“And undoubtedly, current uncertainty is likely to, at best, delay a significant number of international students who would otherwise be making plans, right now, to study abroad in the future.

“These currently unquantifiable factors may cast a chill on student mobility that lingers long after the global health crisis has passed.”

However, even if the physical movement of students across the world is massively curtailed, the financial and educational impacts could possibly be mitigated through the use of international partnerships and technology.

Janet Ilieva, founder and director of another international education consultancy, Education Insight, said the UK could be especially well placed here because of its well-developed transnational sector, which itself grew as a response to previous global shocks such as the East Asia currency crisis of the 1990s.

“Many of the UK universities have the capability to adjust…with increased flexibility [in their] programme delivery or to mobilise their network of overseas partners which they work with in the delivery of UK education overseas,” she said.

“They are likely to be less impacted compared with other countries where this capability is not as developed.”

Although shifting more towards online or distance learning was clearly not a substitute for the campus experience, she said, it could “provide a temporary cushion to students until things get back to normal”.

simon.baker@timeshighereducation.com

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Global sector braces for outbreak’s financial toll

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login