German higher education could be shaken up this autumn by an ascendant political force that looks destined for federal power: the Green party, whose manifesto contains a number of radical proposals that have university heads rubbing their hands with glee.

The party wants to overhaul Germany’s broken student support system; impose a 40 per cent female recruitment target at all levels of academia; and put academic freedom at the centre of German foreign policy.

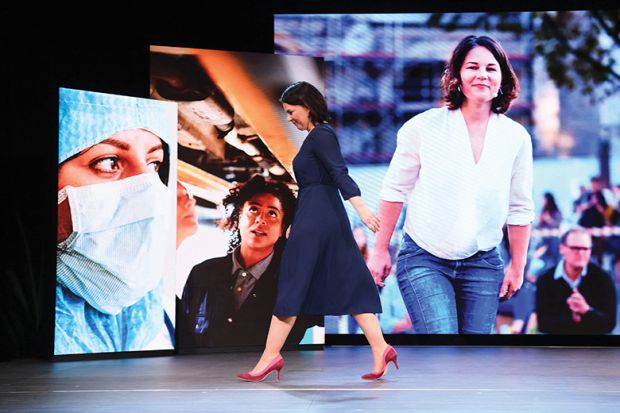

After an election victory in the southern state of Baden-Württemberg in March, the Greens, currently polling a comfortable second, are expected to enter the federal government after September’s election, either as a partner of the ruling conservative Union, or as the leading faction of a coalition of smaller left-wing or liberal parties. On 19 April the party announced Annalena Baerbock, a 40-year-old law graduate of the University of Hamburg and the London School of Economics, as its candidate for chancellor.

The Green manifesto was “unique” for its sheer enthusiasm about science and research, said Peter-André Alt, president of the German Rectors’ Conference.

“It shows that the Greens are interested in making this the motor of future development,” he said. “I’m very optimistic.”

And with several prominent science ministers at the state level, the party is seen as particularly well informed. “They know what they are talking about,” said Professor Alt.

Perhaps surprisingly for a left-leaning party, the Greens seem genuinely excited about spinning out knowledge from universities and into society and industry, bemoaning the lack of a “lively start-up culture” in German research. Two of the party’s MPs recently proposed a new innovation agency called D.Innova, modelled on the UK’s Nesta.

Particularly popular with graduates, the Greens also want to overhaul Germany’s creaking student support system. Bafög, as it is known, reaches less than one in five students. More than three-quarters of student income derives from parents or part-time jobs.

Coronavirus has pushed this long-criticised system well beyond its limits, shutting down the bars, restaurants and cafes on which students relied and forcing the government to step in with emergency handouts.

“The pandemic has demonstrated that this whole thing just doesn’t work,” said Frank Ziegele, director of Germany’s Centre for Higher Education.

The Greens want to give all students a guaranteed income for living costs, with a top-up dependent on parental income and wealth. They also want to widen Bafög to mature students and introduce a legal right to further education after entering the labour market, guaranteeing employees the ability to pause their jobs to retrain.

Their manifesto also promises to make the “defence of academic freedom” a “central aspect” of Germany’s foreign policy.

Green politicians are some of the most critical of links with China on human rights grounds, and their ascension to power could cement an increasing caution in Germany over, for example, Confucius Institutes.

Professor Ziegele doubted that a Green government would directly tell universities which research links they could pursue, but speculated that academic freedom could become a much stronger part of its messaging on human rights.

Also promised in the manifesto are “specific target quotas” to have 40 per cent women at “all levels” of universities, although how this will be incentivised or enforced is not spelled out. “I think these are symbolic things,” said Professor Ziegele. “The question in the end is, will it be a target or a fixed quota?”

The manifesto is still only technically a draft and will be debated by members later this year. And even if the Greens do win federal power, much depends on how ministries are divvied up among parties.

What’s more, higher education in Germany is still officially the prerogative of its states, not Berlin, although federal initiatives and funding have increasingly blurred the line over the past two decades.

But in Baden-Württemberg, where the party has been the dominant governing force since 2011, the signs for universities are promising. Under the state’s science, research and arts minister, Theresia Bauer, budgets have increased by 3 per cent a year for a decade, said Wolfram Ressel, rector of the University of Stuttgart.

She has been “really excellent”, ushering in a “golden time” for universities and speaking regularly “not only with the rectors but also the students, and also all the researchers”, he said.

In 2016 the Greens set up Cyber Valley, a consortium of universities and businesses that claims to be Europe’s largest artificial intelligence research hub. The reason the party is so keen on funding research is that it sees innovation as key to leaving dirty industries behind without inflicting economic pain, said Professor Ressel. The same goes for the state’s mighty carmakers; the Greens want them to go electric, not go bust, he explained.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: German Greens seek radical rethink of higher education

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login