The level of freedom universities have in hiring staff has a strong link to research performance, a Times Higher Education data analysis indicates.

New research published last month by the European University Association gave the latest autonomy scores across four main areas – organisational, financial, staffing and academic – for the university systems of 29 countries and states across the continent.

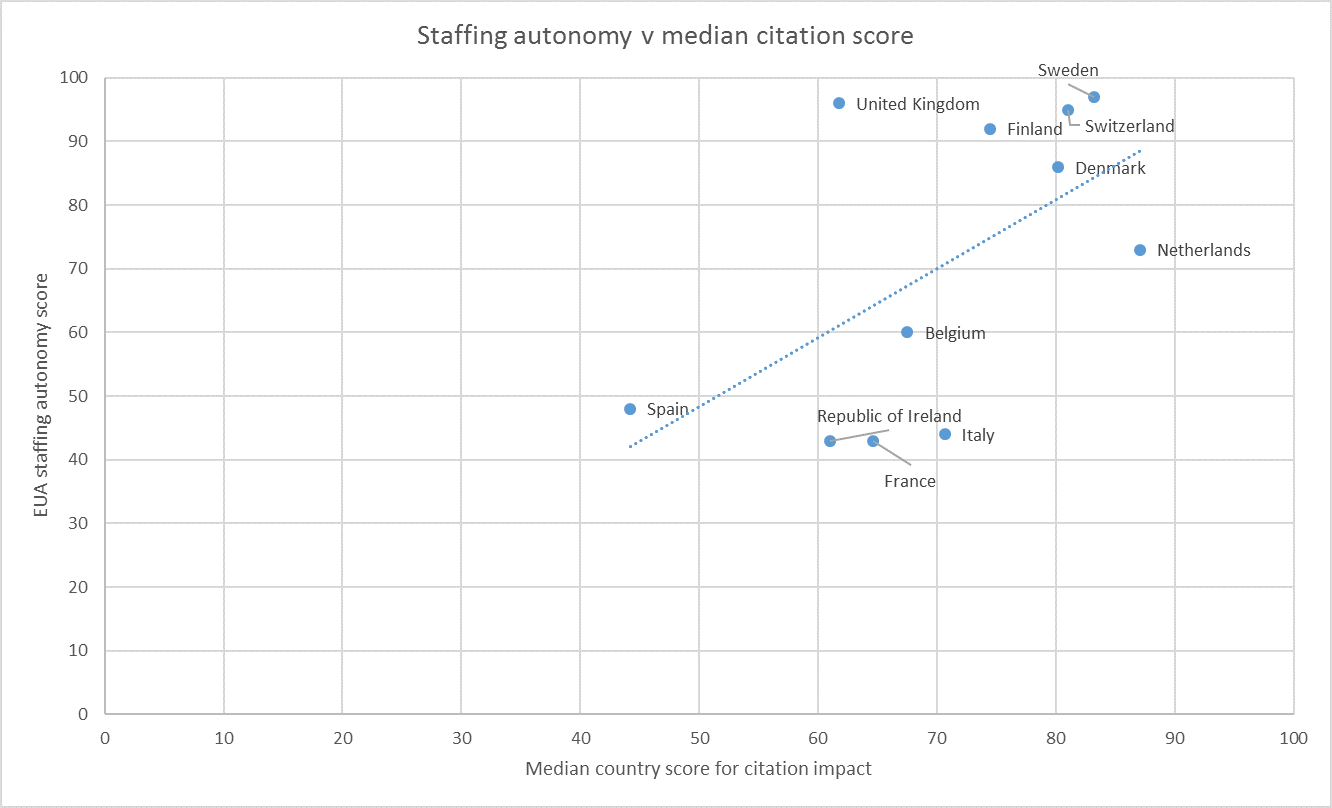

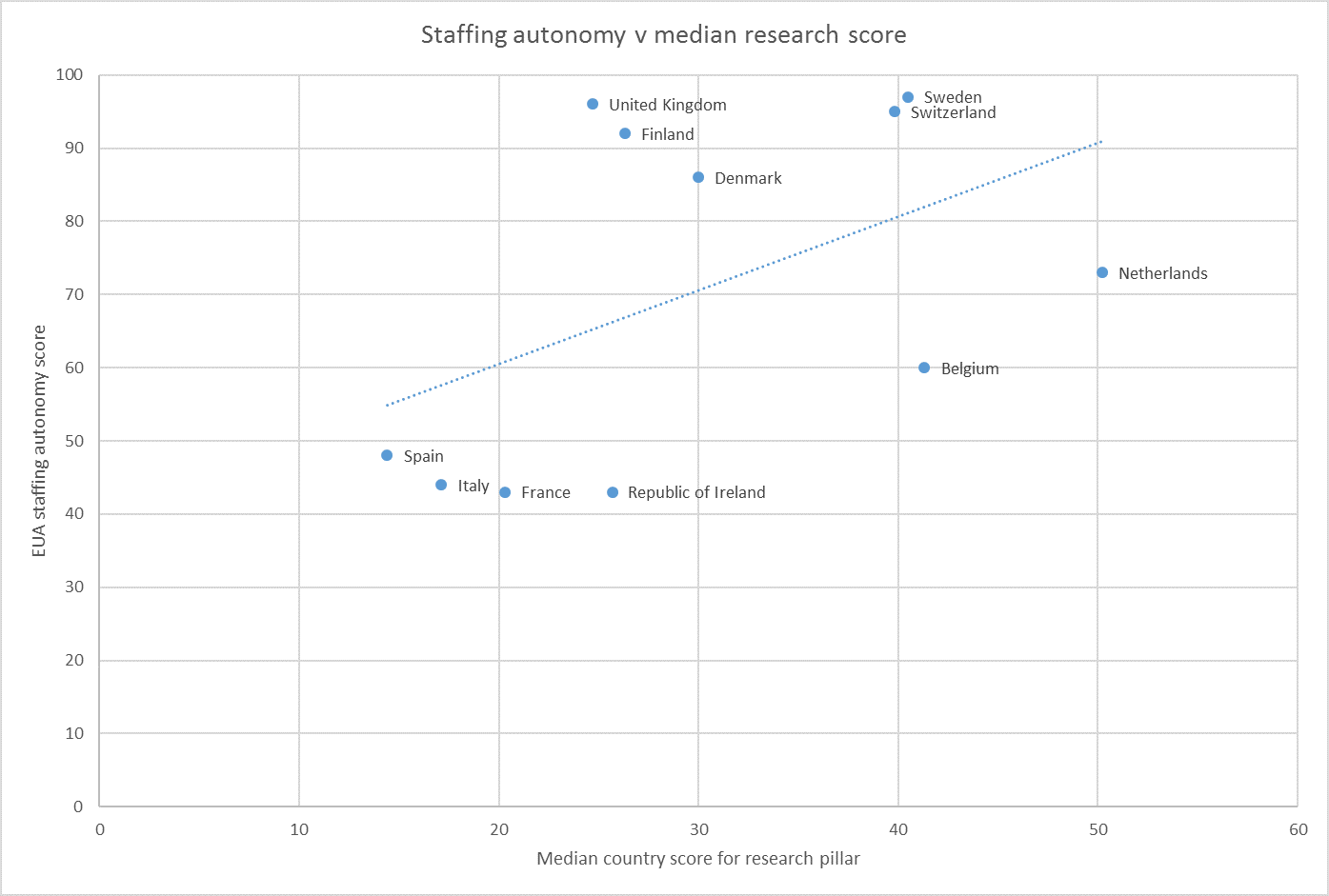

Coupling these scores with THE data on the median citation impact and research scores for a selection of countries, drawn from the World University Rankings, suggests that it is staffing autonomy that appears to have the greatest correlation with these measures of performance (see below) compared with other types of autonomy.

Note: Belgium autonomy score taken as average of Flanders and Wallonia

Those who analyse university autonomy often cite the ability to recruit the best academics, through being able to set decent salaries and offer good working conditions and career prospects, as being vital to institutions’ success.

Thomas Estermann, the EUA’s director of governance, funding and public policy development and co-author of its autonomy report, said countries like the UK, Sweden and Switzerland “have much less regulation” when it comes to staff hiring practices than a country such as France, where university employees are classed as civil servants.

However, he pointed out that although in the UK freedoms in this area are important, there were also other “push” factors such as the research excellence framework – which creates incentives to hire quality researchers – that fed into the overall picture and should be taken into account.

Benedetto Lepori, a professor of higher education at the University of Lugano (Università della Svizzera italiana), who is currently involved in a project comparing university research performance in the US and Europe, also made a similar point, saying that university staffing autonomy needed to be coupled with a good “quality culture”.

He gave the example of some southern European countries where too much freedom in staff recruitment without checks and balances had sometimes led to nepotism.

“If you create autonomy in the hiring of people…where there is some quality culture or there is competition then this is beneficial. But in cases where universities are not used to quality, this might generate dangers of inbreeding (promoting internal people independently of their quality) or, even worse, of nepotism.

“[So] in some Mediterranean countries it was preferred to keep control on staff promotion, particularly for professors, at the state level, as this allows for some quality control across the whole system.

“Also, in some Italian universities, autonomy in financial management led to overspending, as universities were anyway guaranteed by the state and could not go bankrupt.

“Hence, the impact of autonomy depends a lot on the context and autonomy without checks and controls from the state might lead to adverse effects."

Professor Lepori also warned that the biggest threat from Brexit to the UK’s position was likely to be the brake it could put on staffing autonomy through immigration changes for European Union citizens, rather than the impact on research funding itself.

He added: “As soon as you have immigration barriers it becomes very difficult to play in the top league of research, both for universities and for companies.

“I think the big issue [from Brexit] will be much more about regulation around the mobility of people than funding from European programmes. There is a [large] supply of people in academia but the very, very good people are rare and there is fierce competition for them. As soon as you get obstacles to hiring them, for example because of nationality, then…that is the real issue for universities.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login