For better or worse, UK universities have often been placed in different groupings, mainly based on the age of the university (often whether they were established before or after 1992, when legislation allowed for polytechnics to become universities) and the amount of research income they receive.

But differences between the groups have also often been defined by how selective they are when recruiting students.

Up until about a decade ago, this selectivity tended to follow the same groupings, with a clear gap between the grades needed to enter a pre-92 and post-92 university, for instance.

However, 10 years on and after major changes to the system in England that have seen fees triple and recruitment caps on home undergraduates removed, these old lines are becoming increasingly blurred, according to new Higher Education Statistics Agency data analysed by Times Higher Education.

Shift in entry requirements at English universities

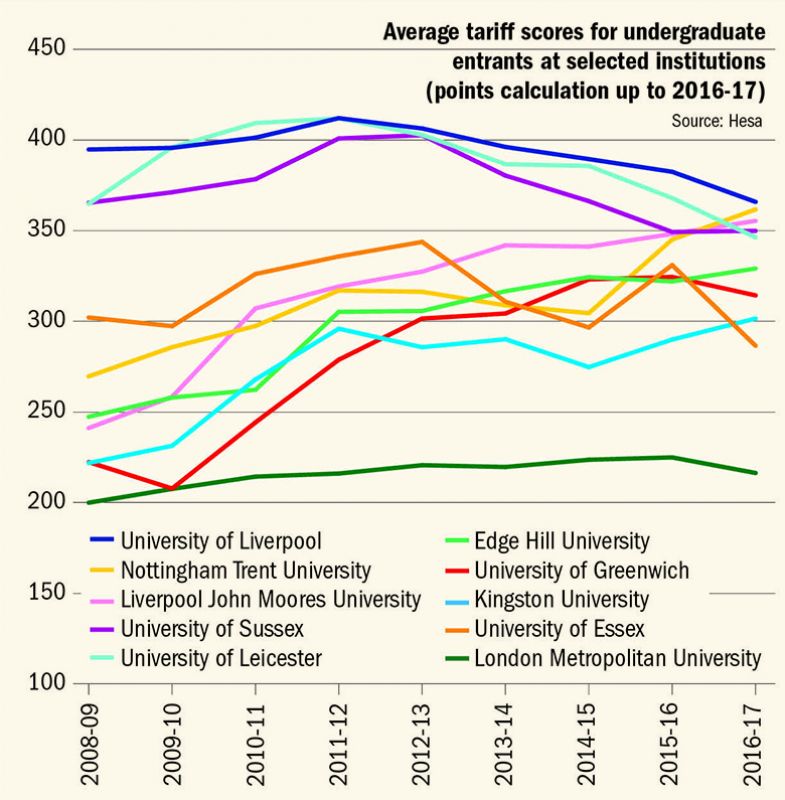

The figures show the average entry “tariff score” of first-year undergraduates at institutions across the sector, essentially a representation of the grades – whether at A level or another qualification – with which the students entered.

Although, according to the latest data in 2018-19, the most selective university remains the University of Cambridge, the order of institutions further down might not always be as expected.

For instance, first-year undergraduates at Liverpool John Moores University, a post-92 university, had an average tariff score of 137 last year (roughly the equivalent of AAB for those entering with three full A levels), just five points shy of the average at the University of Liverpool, a member of the Russell Group.

The shift over time for the sector can also be seen by examining the average tariff at a selected group of institutions where the points change – either up or down – has been high since 2008.

A change in the way tariff points were calculated in 2017 means it is hard to compare the latest data with those from a few years ago, but the data up to 2016-17 suggest that some institutions were recruiting students with more or less the same grades as when there were big gaps between the same universities in 2008-09 (see graph).

Separately, comparing tariff data for the past few years with student recruitment figures suggests that some institutions have cut entry tariffs while also boosting intakes.

The potential explanations naturally point to the big policy changes mentioned above: the shift to universities relying much more on fees for their income and the move towards a market in student recruitment.

Mark Corver, former director of analysis and research at admissions body Ucas and co-founder of consultancy dataHE, said that it was important to be aware of some caveats when looking at such tariff figures.

These included how the changing mix of entry qualifications at different universities – such as the balance between BTECs and A levels – could affect tariff totals given points weightings, and the potential for data to be missing for some students, particularly mature entrants or those using clearing.

But, Dr Corver added, work by dataHE suggested that in the absence of universities really competing on tuition fees, entry qualifications had in essence become the “price” in the system that institutions sometimes chose to raise or lower in a bid to affect recruitment.

“Sought-after higher status providers with effective brand and marketing operations might need only to lower grades a touch to gain transformative increases in students,” he said.

“But growth at this end means that middle-ranking providers might need to reposition grades downwards simply to stand still.”

Dr Corver added that the varying systems across the UK complicated the picture further, with caps on places for domestic students in Scotland, for example, tending to create pressure for the “grade price” to rise for Scottish institutions.

Nicola Owen, deputy chief executive (operations) at Lancaster University, a pre-92 institution whose selectivity compared with other institutions has remained relatively stable over the period, also pointed out that tariff scores fed into domestic league table positions.

This created another trade-off where universities that decided to lower their entry tariff to grow their intake could be doing so at the expense of league table position.

This also sat alongside another “tension” in the system, which was how to allow for recruitment of students from widening participation backgrounds who may not always have the highest grades.

Ms Owen said, in the case of Lancaster, which had a relatively large state school intake for a higher-tariff university, “certainly we have reflected on that tension between tariff and access”.

“It has been a real priority for my university to make sure that we are getting the balance right so that we are still remaining as open” to students with different qualifications or backgrounds, she added.

“But that has meant that if we want to retain our league table position then we have had to be much more focused” on other factors that influence this such as “the student experience and graduate outcomes”, she continued.

Ms Owen said that internal analysis by Lancaster had suggested that in the last few years it was possible to see a correlation at some universities between growing student numbers and lower entry tariffs.

However, many institutions in the sector were facing a key question now in terms of whether they could continue to grow, Ms Owen said, while the overall public funding debate might also pose questions about the financial sustainability of continued growth.

Echoing this, Dr Corver said that the entry tariff landscape could completely change if “UK governments cannot find a sustainable way to finance the required growth in university places over the next decade”, a period that will see a return to growing numbers of 18-year-olds in the domestic population.

“Failure [on public funding solutions] will likely lead to reintroduced and inadequate quotas as an emergency finance control, causing demand to far outstrip supply,” he added. “Entry grades would rocket in response, ‘pricing out’ a large share of the next generation of aspiring students.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Entry tariff data show selectivity gap at English universities is narrowing

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login