English universities could lose £1.4 billion if tuition fees for classroom-based subjects were cut to £7,500 without any replacement in direct public funding, a Times Higher Education analysis suggests.

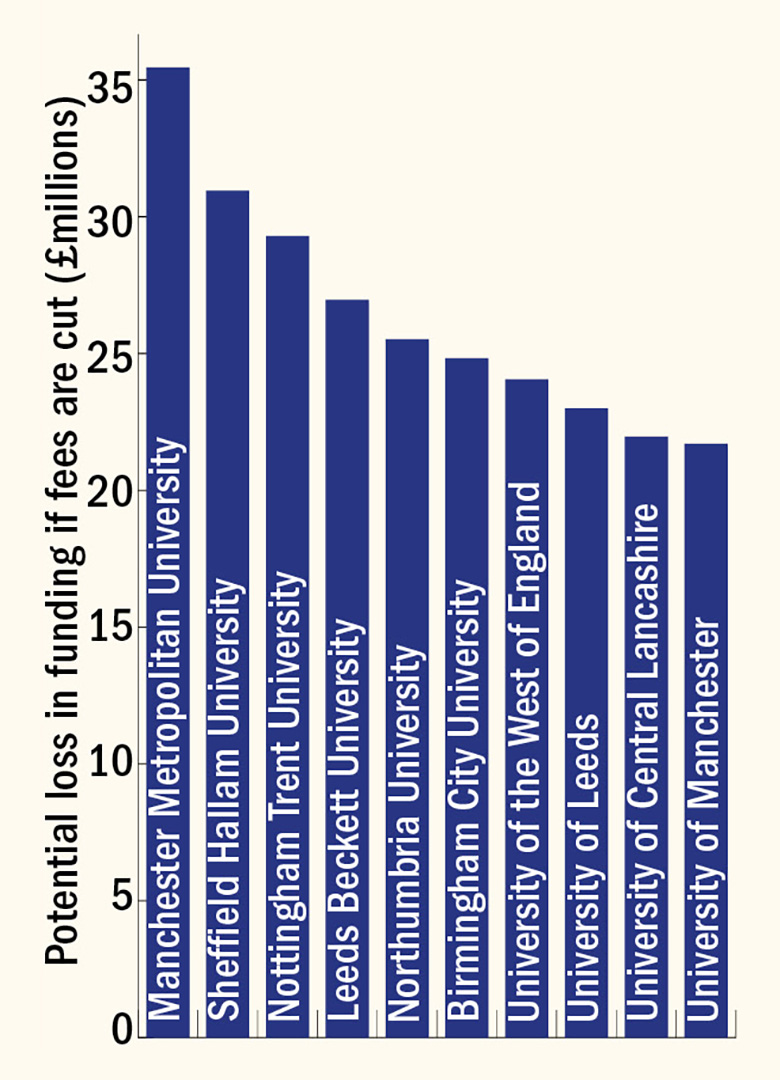

Such a move, said to be under consideration by UK chancellor Philip Hammond, would hit large city-based modern universities the hardest in cash terms, given their greater pool of students on such courses, with five facing a dent of at least £25 million in their annual income. Manchester Metropolitan University would lose £35.5 million, while Sheffield Hallam University faces a £31 million hit.

Major research-intensive universities would not escape such a withdrawal of funding either, with institutions such as the universities of Leeds and Manchester each facing funding gaps of about £20 million.

However, smaller specialist arts colleges would potentially be affected the most in terms of their overall income: 2015-16 financial data suggest that such a fee cut could represent more than 10 per cent of total income at many such institutions.

The findings come from an analysis by THE of Higher Education Statistics Agency data on undergraduate numbers in English universities by “cost centre” – the academic department in which a student is taught.

According to an article in The Sunday Times on 17 September, Mr Hammond is considering a plan to scrap the current fee cap of £9,250 for home undergraduates and replace it with a maximum of £7,500.

The government would then top up the fee with some direct funding per student for those studying higher-cost science and technology subjects. But such a move could mean universities losing £1,750 for students enrolled on any other course.

£7.5K fees: biggest losers

According to Hesa data, in 2015-16 there were about 800,000 UK and European Union undergraduates studying classroom-based and lower-cost science subjects, who were eligible to pay higher tuition fees, amounting to a potential loss in funding of £1.4 billion. The figure could be even higher if replacement funding for each science student was less than £1,750 (the Sunday Times article suggested that it would be only £1,500).

In reality, the full impact of a fees cut might take a few years to be felt if only new students benefited from the change. But the analysis suggests that more than half of English institutions would still eventually face a total funding gap of more than £10 million.

Alan Palmer, head of policy and research at the MillionPlus group of modern universities, said that an “arbitrary” cut in fees could lead to institutions drastically rethinking their provision and closing some departments.

“Reducing the amount of investment in higher education may lead to universities having to take tough decisions over the courses they offer. This could limit opportunities for students and harm the economy if fewer graduates with high-level skills are available to employers,” Mr Palmer said.

He added that the amount of money universities spent on helping disadvantaged students could also be at risk.

On the potential effect for small specialist institutions, Gordon McKenzie, chief executive of GuildHE, pointed out that the government had a duty under the new Higher Education and Research Act to provide a “sustainable funding model” for them and that a shift to £7,500 fees without replacement funding would go against this.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, called for a proper debate on the cost of teaching and graduate employment outcomes, given that the issue of fees being used to cross-subsidise provision was coming to the fore.

A separate THE analysis of Hesa data on direct departmental spending shows that most classroom-based subject areas spent less than £7,500 per student in 2015-16 and that some – including history, law and sociology – spent less than £5,000. A recent Institute for Fiscal Studies report also suggested that classroom-based subjects had disproportionately benefited from the rise in fees to £9,000 in 2012.

However, Mr Hillman said that it was important to consider the effect that a fee cut would have on subjects such as nursing if they did not receive replacement funding.

“I don’t think the sector should be scared about having this debate but I think the sector should be scared about some trigger-happy announcement before we’ve had [it],” he said.

Lord Adonis, the Labour peer who has been campaigning for a rethink on fees, said that it was “quite wrong” for domestic students to be charged more than the operational cost of their course.

He said that the “operation of the current cartel” in higher education meant that “students have no choice to go to a university that offers courses at fee levels that truly reflect costs”.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login