China’s 21st-century explosion as an academic powerhouse has drastically shifted global research towards engineering and away from the humanities, a new analysis of trends since 2000 has revealed.

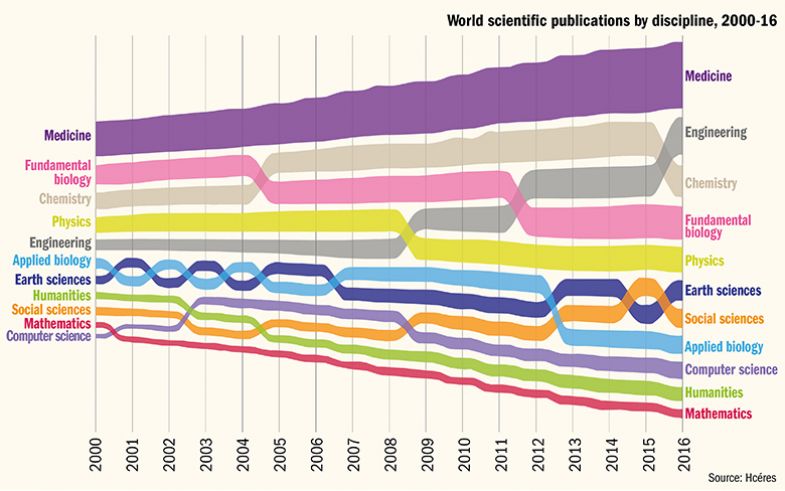

Engineering has overtaken physics, chemistry and fundamental biology to become the second most researched subject behind medicine in terms of articles published, according to an analysis by France’s science and technology observatory, the High Council for Evaluation of Research and Higher Education (Hcéres).

Engineering and the social sciences have expanded their share of world publications by almost 50 per cent, according to the report, while fundamental biology and physics have suffered big falls. Chemistry fell slightly.

“The trend towards a greater relative emphasis on engineering and related fields such as physical sciences, computing, etc, has been showing in science paper counts for some time,” said Simon Marginson, director of the University of Oxford’s Centre for Global Higher Education.

The Hcéres analysis, Dynamics of Scientific Production in the World, in Europe and in France, 2000-2016, looked at nations’ subject specialisation and found that China – which has increased the number of papers it publishes twelvefold this millennium – had homed in on chemistry, engineering and computer science, but had relatively limited output in the humanities and social sciences.

In contrast, the US and UK concentrated on the humanities, social sciences and medical research. France has an edge in mathematics, Japan in physics and South Korea in chemistry. Germany had the most balanced disciplinary profile of the countries analysed.

“National research grant allocation within China is exceptionally pronounced in favour of engineering, and has been for many years,” said Professor Marginson.

China’s research path has been steered by intertwined economic and political motivations, according to Xueying Shirley Han, an expert in the country’s science and technology policy at the Institute for Defense Analyses, a US-based research centre.

“Humanities, along with the social sciences, is a potential avenue for social unrest to bubble up and fester in China and poses too much of a risk to China’s central government,” she said. Science, technology, engineering and maths research, on the other hand, were seen as a way to preserve economic growth and so maintain social and political stability, she added.

There was also an aspect of historical “path-dependency” to China’s research direction, said Richard Suttmeier, an emeritus professor at the University of Oregon specialising in science, technology and US-China relations.

“Fields such as chemistry and engineering have deep roots in modern Chinese history. The field of chemistry, for instance, is well-established and has been led by internationally recognised researchers,” he said.

China’s policy was also heavily focused on development – as opposed to more fundamental research – meaning that it favoured more applied fields like engineering, Professor Suttmeier said.

Engineering has been crucial to the country’s industrialisation and urbanisation since the late 1970s, Professor Marginson said, and has fed into improvements in transport, construction, communications and energy.

A world without China, the Hcéres analysis says, would be “noticeably different”. Medical research would make up a full quarter of publications (as opposed to 23 per cent when China is included), while fundamental biology would still account for more papers than chemistry.

Nonetheless, “in this counterfactual world, engineering would still have moved up to second place since the start of the century”, it says.

Engineering’s rise was not just evident in China, said Professor Marginson, but across East Asia – in Singapore, South Korea and Japan – and also other “emerging research systems” such as Iran.

It was also beginning to spill over into more established countries such as the US, he said, pointing to Harvard University’s new 500,000 square foot science and engineering complex, currently under construction but expected to open next year.

A spokesman for the US National Academy of Engineering said that the Hcéres conclusions echoed other work pointing to a rise in the importance of engineering.

The humanities, meanwhile, have moved in the opposite direction, slipping behind both the social sciences and computer science since 2000, according to Hcéres’ analysis.

In response, however, representatives of the discipline questioned whether it was even possible to accurately measure the fortunes of a subject area more structured around books than journal articles.

International publication output per discipline

The data are drawn from Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science, an ever-changing database that adds new journals as they are founded to incorporate new disciplines, and also absorbs existing journals to better reflect academic research outside the English-speaking world.

Using this database to track changes in published journal articles “makes perfect sense for the sciences”, but not for the humanities, said Robert Townsend, director of humanities indicators at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The humanities’ relative decline in published articles could still illuminate the changing pressures on academics in other disciplines, he said.

“One of the potential questions would be whether it’s a function of the length of the articles that are appearing,” Dr Townsend said.

In the sciences, there was growing pressure to publish even partial findings to be the first to a discovery; on the contrary, there is “none of that in the humanities”, he argued.

“It has a self-reinforcing effect because in the sciences you’re measured by the number of articles you do,” Dr Townsend said, while in the humanities, at least in the US, books remained more important for promotion.

“It opens up a lot of interesting questions about how scholarship is done,” he said.

Given cuts to humanities funding in some countries, “there’s certainly a possibility that the funding picture is having some impact on these things”, Dr Townsend continued.

US humanities research funding flatlined from 2007 to 2010, before rising again, according to data from the academy.

However, there may be no straight line between funding levels and numbers of publications. For one thing, there will be a lag between funding decisions and a change in output, Dr Townsend pointed out, and a particularly long one in the humanities.

In addition, “it costs so much more to do science research”, he said. “You don’t have big labs...in the humanities.”

Harriet Barnes, head of higher education and skills policy at the British Academy, which promotes the humanities and social sciences in the UK, said that the journals added to the Web of Science database over the period studied “are far more likely to have been in social sciences than humanities, which could well account for the increased proportion of social science publications as part of the whole”.

The Hcéres analysis calculates that two-thirds of the increase in social science articles since 2000 was down to the addition of new journals to the database, as opposed to growing publication volumes in existing journals. Still, it was not clear to what extent this represents “real” growth: these new journals could be newly founded, or could have existed for years but only recently incorporated into Web of Science.

There is also a question as to whether China might be much stronger in the humanities and social sciences than the statistics suggest. “Publications in the humanities are the most likely to be in languages other than English and hence not often captured by the standard databases and so even where developing countries are increasing their research capacity in humanities, this is much less likely to be reflected in studies such as these,” said Ms Barnes.

“An in-depth review of Chinese journals in the humanities and social sciences would be required before reaching any definitive assessments of Chinese work in these areas,” Professor Suttmeier added.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Engineering booms, humanities falls as China reshapes research

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login