As the Covid-19 crisis has gathered pace around the world, a number of scientific voices have been amplified in the debate as the public and governments search for advice, reassurance and facts about the pandemic.

Often, these have been experts who were already in prominent positions advising administrations, such as England’s chief medical officer Chris Whitty, or those appointed as part of the response to the crisis, like Anthony Fauci in the US.

But there are others who have come to the fore because of their specific expertise, perhaps most notably Germany’s Christian Drosten, director of the Institute of Virology at Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, who, thanks to a regular podcast on the pandemic, has become one of the country’s chief commentators on the outbreak.

What is particularly interesting about his high public profile, compared with that of other publicly engaged scientists around the world, is that he has genuine expertise on the virology of coronaviruses.

His work has tracked coronaviruses from the Sars outbreak in the early 2000s (he was one of the first researchers in the world to identify the virus behind the disease) through Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Mers, where he was involved in studies that established its prevalence) to Sars-CoV-2 and Covid-19.

It is an expertise that is also clearly evidenced by bibliometric data on coronavirus research.

Renowned names: Key figures in the field

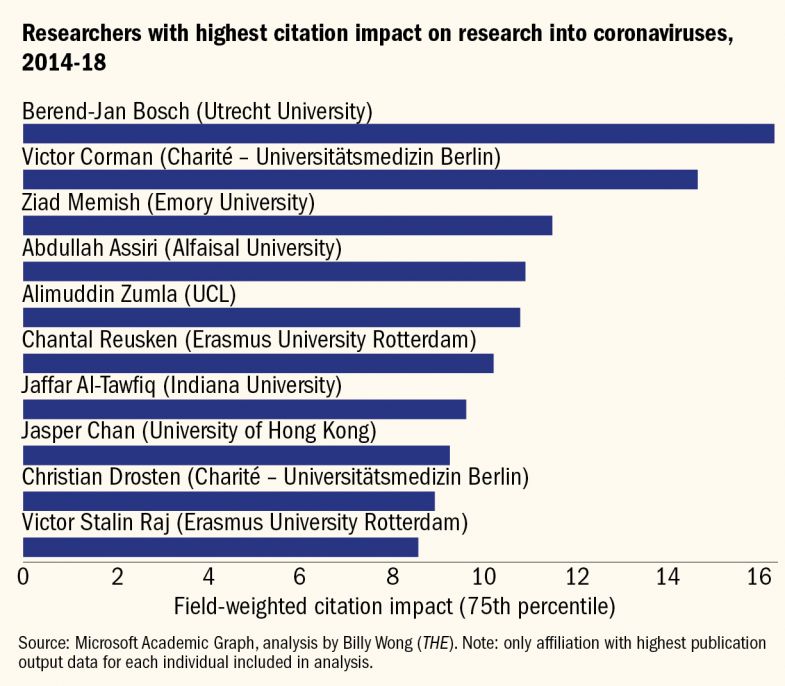

According to an analysis of Microsoft Academic Graph (a collection of research publication data) on coronavirus research, Professor Drosten is among the top 10 for citation impact, while his Charité colleague Victor Corman, who helped to develop a diagnostic test for the Covid-19 coronavirus, is also high up the list.

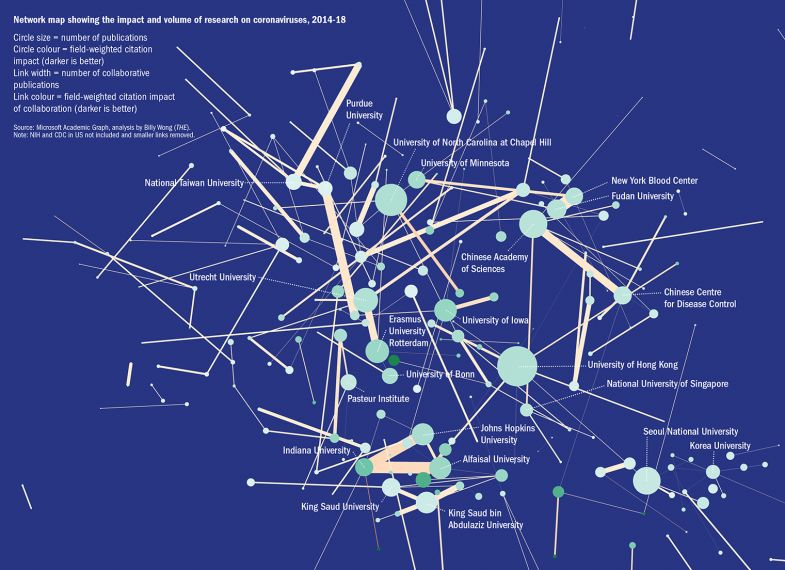

Times Higher Education’s lead data scientist Billy Wong, who analysed the Microsoft data on coronavirus papers, was also able to pinpoint the key institutions and collaborations in the field using a network map (see graphic).

Cluster effects: Powerful collaborations working on coronaviruses

It shows a number of powerful research clusters that have developed globally in the field in recent years, with particular centres of expertise at the University of Hong Kong (which was closely involved in work on Sars), in the US (most prominently involving the University of North Carolina), in Europe (centred around Utrecht University and Erasmus University Rotterdam) and in the Middle East (likely a reflection of research on Mers).

Among the other individuals to feature highly in the field are Berend-Jan Bosch, a coronavirologist at Utrecht University who has just co-authored new research identifying an antibody that fights Sars-CoV-2, and Ziad Memish, former deputy minister of public health in Saudi Arabia, who worked with Professor Drosten to investigate Mers.

In a recent article in Science, the head of the German Science Media Centre said it was a “stroke of luck” that, in Professor Drosten, Germany had a recognised expert on coronaviruses who was also “willing and able to communicate so well”.

But does the apparent lack of other prominent voices with specific expertise on coronaviruses mean that the public – and governments – elsewhere are sometimes getting a distorted picture of the science around the pandemic?

One question raised in the UK has been whether epidemiological modelling – an area where the country has world-leading experts – has taken too dominant a role in informing the government and the public debate.

Scientists who have had a lot of media exposure include modellers who have been feeding into government advice, such as Neil Ferguson of Imperial College London.

However, Fiona Fox, founding director of the Science Media Centre (SMC), said that although she was aware that some disciplines had complained they were not being represented in the advice to government, it was very difficult to tell if this was true.

This was partly because the membership of the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) was initially shrouded in secrecy. As a result, people may have concluded there were too many modellers simply because the Sage members who were happy to talk to the media were from that discipline, such as Professor Ferguson.

Generally, whether the public sometimes got a distorted view of science issues because some academics were more willing to engage publicly was an interesting question that could be worth exploring, Ms Fox added.

Although the hundreds of scientists on the SMC’s media contacts database cover every discipline, volunteering to join a government advisory committee or to speak to journalists “is not for everybody”, and many academics might consider such undertakings to be “time out from your laboratory” and the important work they were doing, she explained.

“In that sense, it is self-selecting. You are getting the kinds of scientists who think it is good to engage with the public…but you would have to do some kind of PhD to work out whether that distorts [the information] the public are getting,” Ms Fox added.

David McCoy, professor of global public health at Queen Mary University of London, said one of his worries was that the way science was structured and funded in the UK meant that researchers sometimes did not give enough thought to how their work translated to the world of public policy.

Part of this, he added, reflected the increasing separation between research and teaching. Teaching “requires you to make your research relevant to students” and to place it in a wider context, Professor McCoy said.

As a result, he explained, “I think we’re getting researchers who are less able to translate their research findings into policy-relevant recommendations.

“Partly because science has expanded so much, many researchers have had to plough increasingly narrow furrows and focus on their area of specialisation. This makes it harder to make horizontal linkages with the research of other disciplines and other subject areas.”

Professor McCoy said this ability to make connections across different subject areas and types of science was a particularly vital skill for those experts engaging with public policy, as compared with those with a strong research record in one specialist area.

And although a long publication record “signals that you are a good scientist, it doesn’t necessarily mean you also have the skills to make good policy judgements, which inevitably involve ethical issues, political and economic considerations, and the management of trade-offs; nor does it necessarily mean you are a good communicator”.

“Good scientists don’t necessarily make good policy experts,” he said. “We have lots of scientists who are expert in one or two things, but perhaps not enough who have breadth and the confidence to straddle the divides between the natural sciences and the social sciences and the humanities. For me, that is what is required, and [that is] what is missing.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Have other scientists in debate eclipsed coronavirologists?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login