A former Ucas boss has called for “common sense” to prevail as the political wind blows towards a post-qualification admissions system in England.

Gavin Williamson, the education secretary, wrote to the Office for Students last week to express his support for the higher education regulator’s review of university admissions, which includes consideration of the “pros and cons of potential models of post qualification application”. Mr Williamson said he was “glad the OfS is looking at whether it would be in students’ interests to apply for their university place after they have their A-level results”.

Labour has already pledged to abolish the system of making university offers based on predicted grades. Meanwhile, Universities UK is carrying out a review into the admissions system, in parallel to the OfS review.

Although the apparent political backing for universities to adopt a PQA system might suggest that such a move is now inevitable, it is likely to meet resistance from within the higher education sector, including from Mary Curnock Cook, the former Ucas chief executive.

“I was personally very committed to PQA until I saw the evidence,” she said. “My hope will be that the political imperatives will be balanced by common sense in the face of evidence.”

For Ms Curnock Cook, leaving students to make their university applications after they have left school “would carry great risks, even if the universities were prepared to move their start date to January – which, for multiple reasons, they would be very reluctant to do”.

The risks would be “especially acute” for students from disadvantaged backgrounds “because they might not have the momentum from family and community to press on with a university application after having left school”, she warned.

A University and College Union report proposed a system in which applicants make “expressions of interest” to up to 12 institutions in the January of the year of application. This would be followed by an application week in August, after students have received their grades, placement by the end of September and the start of the first academic year in November.

One of the authors of that UCU report, Graeme Atherton, of the National Education Opportunities Network, said it was not simply a case of taking the current system and “just shifting it for the students to apply after they get their results”.

“You have got to look at changing the system as it is constructed,” he added, calling for a far greater emphasis in supporting and advising pupils about higher education study options while they are at school. “The key thing is that we advocate a change in the overall admissions system to enable students to be better supported to make decisions.”

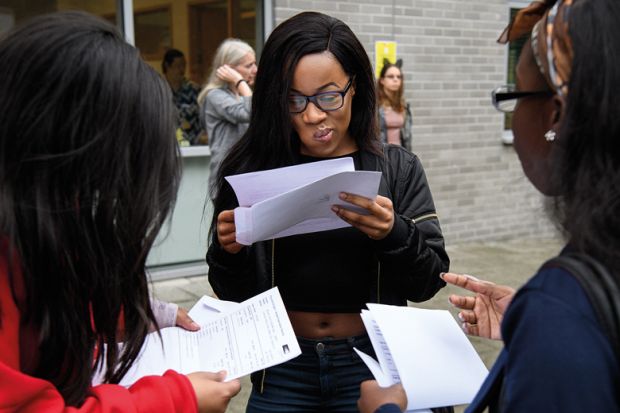

The current predicted grades system is seen by many to penalise poorer and ethnic minority students.

Another UCU report on PQA, by Gill Wyness, senior lecturer at the UCL Institute of Education, found that AAB applicants from the lowest-income backgrounds were under-predicted more frequently than their peers from higher-income backgrounds. Overall, Dr Wyness’ report found that just 16 per cent of applicants’ grades were predicted accurately, with the majority over-predicted.

Research by Vikki Boliver, a professor of sociology at Durham University, found that university applicants from disadvantaged backgrounds were less likely to apply to Russell Group universities than their more advantaged peers, even when they had the same grades at A level.

“More disadvantaged students might see highly selective universities as within their reach if they are applying with high grades in hand, rather than mere predictions (and possibly under-predictions at that),” Professor Boliver told Times Higher Education.

Other concerns raised about the current system include what Mr Williamson described as a “worrying rise” in unconditional offers made to students, particularly “conditional unconditional” offers, which become unconditional only when an applicant selects the university as their firm choice.

Ms Curnock Cook said that changing the academic calendar would present “multiple challenges”, including changing staff teaching and research contracts and disrupting the UK’s position in the international recruitment calendar.

Julie Kelly, head of the Student Centre at the University of Hertfordshire, said it would require a “compromise all round”, among schools and universities, to implement a new system.

“In the past, it has been put in the ‘too difficult’ pile, but other countries manage it,” she added.

Ms Kelly said the nature of the current system truly hit home for her only when her daughter applied to university. She described the current predictive grades system as a “bit like looking for a house or buying a car when you don’t know what you can afford”.

“It just feels like the weirdest, broken process. Until I really personally went through it, I didn’t realise how broken it was,” Ms Kelly added.

An OfS spokesman said that its review, which will report next year, was at a “very early stage” but would be “wide-ranging”, with terms of reference published towards the end of this year.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Post-haste? Don’t rush to PQA, sector figures counsel

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login