Ben Altshuler is a sponsored researcher at the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents (CSAD) at the University of Oxford. He has worked on Greek vase paintings, using scanning techniques to “look at mistakes and sketches covered up by the last layer of paint”. He has also tried to penetrate “the lowest layer of text” in palimpsests owned by the Vatican.

“Little technology is created by archaeologists,” he says, “because less funds are always available than in science and medicine”, but that hasn’t stopped them piggybacking on the latest innovations and, for example, performing CAT scans on mummies.

And that also means Mr Altshuler is “constantly looking out for scientists interested in the Classics”.

His work on the Vatican manuscripts, for example, drew on methods Nasa uses for observing forestry and identifying minerals from space, bringing in “people from space observatories who knew how to work with and manipulate ultraviolet and infrared images”.

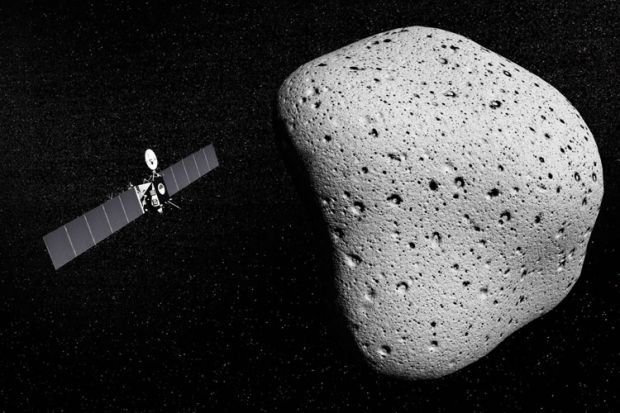

The Rosetta space probe and its Philae lander module were launched in 2004. Since they were designed to unlock some of the mysteries around comets and the origins of the solar system, they were named after two of the objects – the Rosetta Stone and the Philae obelisk – which proved crucial in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The obelisk has been kept outside at the Kingston Lacy country house in Dorset since 1820 and has long been something the CSAD wanted to work on.

When they heard about the space mission named after it, Mr Altshuler explains, they decided to seize the opportunity and “found funding to put up scaffolding” to read sections of the text which have always been illegible and have now been battered by the English weather for almost 200 years.

Similar multispectral imaging techniques, notes Mr Altshuler, have now been used to “analyse the surface of the comet, both its shape and its make-up” and to “pick up old paint that was once used on the obelisk’s inscription”.

To celebrate these dual achievements, the Classics Conclave – a US-based funding body which supports the application of technology to the study of the ancient world - joined forces with Kingston Lacy and the European Space Agency to host a celebratory dinner last week. This also gave Mr Altshuler a chance to “meet with space scientists and see where there could be connections, how Classics could use their technology”.

“There are crossovers,” he confirms, “though most of their equipment is out of our budget”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login