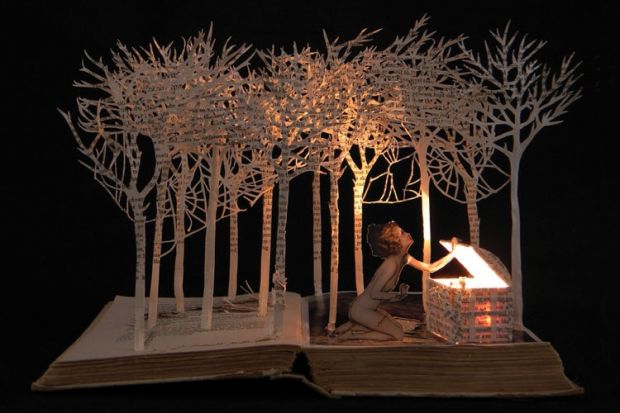

Source: Su Blackwell

When young academics feel constrained to use a certain specialist language then academic freedom has been compromised

Reading is an activity that can easily be taken for granted – by the literate. Most of us are fortunate enough to have learned to read as children and it isn’t until we come to teach someone else, often our own children, that we begin to consider the complexity of the process. But it’s something we need to continue to think about, not “just do it”.

As academics, teachers, students and citizens, we need to be wary of language and its sometimes insidious ways. We need to know when words are trying to persuade us of things that we would do best to not be swayed by. At the same time, as writers, we should always be conscious of the need to contribute towards a fundamentally important collaborative project – that of ensuring that the life blood of the language we use is as healthy as it can possibly be.

What I’m arguing for is something that goes a good deal further than the Plain English Campaign, which has been “fighting for crystal-clear communication since 1979”. It’s a pressure group I admire and its battle against gobbledegook, jargon and misleading public information is an important one. What I’m advocating, however, is not simply clarity and precision, what used to be called “plain English”. What I’m arguing for is an attentiveness to language when reading, and a self-consciousness when writing, that together foster a creative use of words.

It is only an imaginative use of language that allows for the emergence of new ideas and a new understanding of ourselves and the world we live in. We need to be linguistically inventive and ingenious if new insights are to be conceived of and articulated. And we also need to be aware of language that is no longer fit for purpose. It is incumbent on us to do something about words that have lost their vivacity and lounge lazily on the page.

C. S. Lewis inveighed against the practice of verbicide – or the killing of words – a concept that was first proposed in the middle of the 19th century. Of course, words can’t be “killed” in a literal sense, but damage can certainly be done to them. For Lewis it meant hijacking words in order to use them to make evaluative judgements. His examples included “awesome” to mean “excellent”. “Awesome”, as far as Lewis was concerned, meant “inspiring awe or dread”. As I was writing this piece, using Microsoft Word, I clicked on synonyms for “awesome”. Up came “no suggestions”. The word has been confused. Another recent example of verbicide would be “wicked” to mean “excellent”, rather than “evil”.

But I’m not altogether sympathetic towards Lewis’ concerns, as one of the things that I love most about language is its instability: its capacity to change, reinvent itself and even, in the case of “wicked”, to all but reverse its meaning. Any assaults on language that reduce it are unwelcome, but I think we can still use “wicked” to mean “evil”, as well as “playfully mischievous” and “wonderful”. The context would allow for any of these. I’m more concerned by another linguistic phenomenon that could also be deemed a form of verbicide, and that’s cliché.

With due respect to the Plain English Campaign, I’d like to consider the use of its slogan, “fighting for crystal-clear communication”. “Crystal clear” is a cliché and as such we read it as though it were a hieroglyph. The brain recognises the phrase as meaning simply “very clear”. We no longer see and appreciate the extraordinariness of a solid mass of mineral that is transparent. It’s miraculous that crystal exists in the world and it is no surprise that it is highly valued. I was on the north coast of Devon recently and had a wonderfully blowy walk along the beach in wellies. I was strolling along the water’s edge enjoying the sense of disorientation that looking down at the froth running this way and that causes. The water, I reflected unimaginatively, was “crystal clear”. And then I thought of clear water, its transparency and the idea of likening a fluid to a solid, “crystal-clear water”. The cliché, “crystal clear”, had come back to life and all the sensual pleasures of a beach walk were confused with the pleasures of rediscovering words and wondering about things of which I had no knowledge – in particular, “liquid crystals”. I was both there, in the moment, seeing, listening, tasting the salty air, feeling the numb swirl of water around my boots, but also conscious of the inseparability of life and language. And the cliché “crystal-clear English” started to worry me. I don’t think we should want language to be “see-through”, I think we need to see the words and question what they’re up to.

In passing I should say that I don’t believe we need to worry about small children reading clichéd writing. The great thing is that they don’t “see through it”. They see all the words. I remember one of my children asking what the phrase “once upon a time” really meant. He knew it meant “at some point, perhaps long ago” and he knew that it was an opening phrase, promising a story. Without knowing what a preposition was he was bothered by the “upon” in the expression. I looked up the expression and discovered that it was very old indeed. It goes back at least to the 14th century. By 1600 it was well established as the opening of fairy tales. But children don’t recognise the clichés or the hackneyed plots – it’s all still new to them.

Those who argue against cliché often criticise the reading of escapist literature. This is prejudice and here I’m talking about both children’s and adults’ reading. All reading is escapist in so far as the reader loses himself or herself, and lives, vicariously, in another world, the world conjured up by the book. This is as true of a history book as a novel. It is also true of other forms of narrative non-fiction, biography, autobiography and so on. It is equally true of some science writing. There is no harm in escape per se. What is important is where the reader escapes to, and that is a matter of debate in relation to particular pieces of writing. It can also be a matter of legal process. When the full unbowdlerised edition of D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, written in the 1920s, was published by Penguin Books in Britain in 1960, the publisher was prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act 1959. The Act allowed for works of “literary merit” to escape prosecution regardless of the use of “obscenities”, in Lawrence’s case the words “fuck” and “cunt”. The prosecution lost the case and when Penguin published a second edition, in 1961, it included a dedication: “For having published this book, Penguin Books were prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act, 1959 at the Old Bailey in London from 20 October to 2 November 1960. This edition is therefore dedicated to the twelve jurors, three women and nine men, who returned a verdict of ‘Not Guilty’ and thus made D. H. Lawrence’s last novel available for the first time to the public in the United Kingdom.” The trial resulted in more than that; writers had greater freedom to experiment with more colloquial language and more daring plots.

So, to where do books allow us to escape? One of the best accounts I’ve come across is by the French publisher, author, translator and bibliophile Jacques Bonnet. In his whimsical book, Phantoms on the Bookshelves – an exploration of books, personal libraries and how they are the repositories of our innermost feelings – he writes: “The discovery of reading…penetrated like a shaft of sunlight, through the gloomy atmosphere of a provincial childhood…The children, they were, to put it briefly, daily confronted by the authority principle. To take just one example: in 1967 it was still forbidden to bring a daily newspaper – even serious ones like Le Figaro, Combat or Le Monde – into a French state lycée. The tedium of childhood could be fought only by two things: sport and reading. And reading was something like the river flowing through the Garden of Eden…Reading scorns distance, and could transport me instantly into the most faraway countries with the strangest customs. And it did the same for centuries of the past: I had only to open a book to be able to walk through 17th-century Paris, at the risk of having a chamber-pot emptied over my head, to defend the walls of Byzantium as they tottered before falling to the Ottomans, or to stroll through Pompeii the night before it was buried under a tidal wave of ash and lava. I noticed after a while that books were not only a salutary method of escape, they also contained the tools that made it possible to decode the reality around me…Escape and knowledge: it all came from books.”

As a writer I am, needless to say, a supporter of books and reading. I am an interested party. But if we are to avoid being caught up in self-contained linguistic prisons where everything that is said is, in effect, repetition and cliché, then we have to attend to words and their efficacy. Academic jargon can create just such a closed space in which the initiated talk to one another and there are far too few reality checks. Peer review, rather than acting as a control, can further strengthen the in-language and in-thinking. The pressure on academics to contribute to the research excellence framework can be yet another threat to the independence and integrity of the academic as writer.

When young academics feel constrained to use a certain specialist language then academic freedom has been compromised and young scholars operate in an oppressive space unlikely to be one favourable to new ideas. In the humanities, as in many other disciplines, mounting pressure to secure vast grants for collaborative research projects is a further threat to academic freedom. The projects that are successful are all too often mechanistic. Some are important and worthwhile and often involve the setting up of vast databases. But the purpose of these databases should be to allow individual researchers to explore them over long stretches of time, to get to know them in all their often bewildering size and complexity, and make of them what they will – in their own language.

“If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.” Who do you suppose proposed reading fairy tales as a stimulus to intelligence? It was Albert Einstein. What matters is to be able to believe in the unbelievable. It’s a precondition of creativity, of new inventions. Everything has to be imagined before it can be. And it’s 26 letters and a handful of punctuation marks that are the ingredients of a fairy story – and all manner of other types of writing.

Recent research has proved Einstein right. Children who read for pleasure are likely to do better in maths and English than those who rarely read in their free time, according to research published in September. The study, by the Institute of Education, University of London, examined the reading habits of 6,000 children. They concluded that reading for pleasure was more important to a child’s development than how educated his or her parents were. And one way to get children hooked on reading is to read them fairy stories when they are little. We need to encourage children to become great readers, to have wide vocabularies that put them in touch with all aspects of life. We also need to encourage suspicion of language and attentiveness to its vagaries – and its wonders. We can only do these things by example.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login