The burial site of Viking kings, a pagan centre in medieval times, and the seat of Sweden’s Catholic archdiocese since 1164, Uppsala, north of Stockholm, is today watched over by the Carolina Rediviva, one of the world’s great academic libraries, which sits atop a hill above the city.

Among other things, the library of Uppsala University – the oldest university in the Nordic countries – holds every book published in Sweden as well as a huge number of foreign works seized from all over Europe by Swedish kings, including the Codex Argenteus, a Bible transcribed in the 6th century.

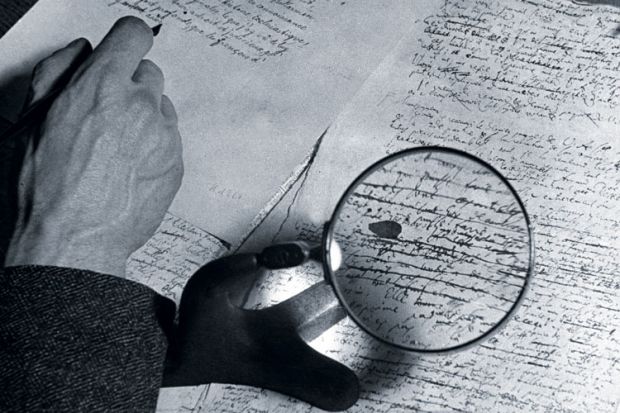

But good luck finding what you need from some of the materials that predate the invention of moveable type. Researchers here, as all over the world, have been stymied in their attempts to digitise handwritten manuscripts.

Optical character recognition, which can convert type into searchable digital files, cannot decipher handwriting; handwritten text recognition, which can read simple things such as figures on bank cheques, is not yet sophisticated enough to reliably transcribe archival texts.

Now a five-year, Skr13.7 million (£1.08 million) project at Uppsala – From Quill to Bytes, which is referred to as Q2B, or “Google for handwriting” – is seeking to develop ways of deciphering these works.

“If you take a modern printed text and OCR it, you get it right up to 99 per cent of the time,” said Per Cullhed, strategic development manager for the Uppsala University Library. “But if we use the same applications for a text from the 14th century, half of it could be just nonsense.”

The result, he said, is that “all archival materials, everything that’s handwritten, all the books from medieval times – all of that is not available in a way we’d like to have available”. Discovering how to make them searchable, Mr Cullhed said wistfully, is “the holy grail”.

The team in Uppsala is up against competitors from three Swiss universities, who are working on the Historical Document Analysis, Recognition and Retrieval (HisDoc) research project, as well as a European Union collaboration called tranScriptorium, which has brought together experts from universities in Spain, Austria, Greece, the Netherlands, University College London and the University of London Computer Centre.

Typical success rates on these projects have ranged from 8.9 to 33.5 per cent of handwritten text being recognised by optical sensors. A big problem is isolating characters, which are often faded, smudged or too close to the “noise” of margins and illustrations.

“The basis of what they’re working on is even more irregular than printed text: different hands, different manners of writing, different writing tools from different times,” Mr Cullhed said.

He is optimistic that these problems will be solved, he said, but “to have something that really opens this up, it’s quite far away”.

When that solution arrives, he said, people will still be needed to check the work, perhaps through crowdsourcing – which the Smithsonian Institution in the US already employs, using human “digital volunteers” to read and transcribe handwritten documents.

Yet even then, he continued, “you will always need the primary sources”. But if one day researchers of ancient texts can quickly home in on what they seek in a vast library, it will mean the holy grail has been found.

POSTSCRIPT:

Article originally published as: View to a quill: illuminating manuscripts for the 21st century (18 June 2015)

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login