Many students that choose to pursue business, social science or psychology courses think they’ve left their maths anxieties behind them. Having not studied maths since GCSE in some cases, the mathematical and statistical demands of many of these courses can come as a shock to students. In a 2019 study from The Nuffield foundation, only 26% of students demonstrated the numerical skills and understanding identified as generally necessary for daily life and work. Or in other words, the functional equivalent of a ‘C/4’ at GCSE.

While many institutions will require specific grades and maths qualifications to get entry onto their course, students can sometimes bring their maths anxiety with them, even if they have the relevant qualifications to begin their course.

In psychology, for example, a study found that up to 80% of psychology students experience a level of statistics anxiety and that many, when given the opportunity, would regularly push back on the statistics elements of their courses until their final year. Not only do they not feel confident in their own skill, but they struggle to see how the maths and statistics elements of their course are relevant to their overall success.

For frontline educators, a lack of mathematics knowledge can mean that too much time is spent explaining concepts and bringing critical thinking skills up to standard, instead of focusing on core subject matter. Where the time isn’t available to develop skills and understanding to the required level, students’ progress and completion rates may be impacted.

Removing the anxiety

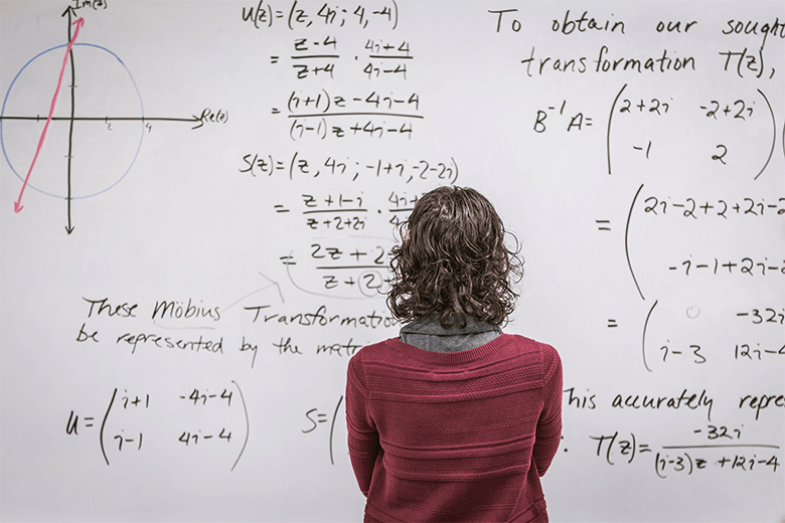

Maths anxiety, which sees students either putting off or procrastinating in completing the maths elements of their courses and freezing during exams, has been identified as an issue leading to poor numeracy performance. Additionally, this can be precipitated by fears around their ability and can lead them to adopt a surface learning approach; passively taking in information and regurgitating it for exams – rather than seeking answers and making connections with the wider subject matter themselves.

For time-pressed lecturers, the ability to adapt maths teaching to each student’s individual level, personalise to their learning styles and provide the regular, individualised feedback at scale that is proven to improve results, is a huge challenge without technological support. If they are able to engage with the maths and stats exercises outside of their traditional classroom setting, they may find they are happier to make mistakes and less anxious asking questions, especially where automatic feedback can be given.

Real world application

A recent Cambridge Assessment study suggested that the issue is less about maths ability, and more about applying maths in context. Many students tend not to engage with the maths elements of their course because they fail to see it’s relevance to their overall degree. Lecturers from several Russell Group universities were interviewed in the study to uncover the problem of declining numeracy skills. Across all undergraduate subjects, participants reported that students struggled to apply their maths knowledge in unfamiliar contexts, select the appropriate mathematics method to solve problems, understand the relevance of maths to their subject (particularly in biology and psychology) or ‘translate’ a problem between maths and their discipline; e.g. economics.

It may be worth spending some time establishing how the maths is relevant to their course in core modules and taking an integrated approach to maths or statistical modules. Through this method students can engage with real world exercises, examples, and case studies that place maths in context. While this may seem like an additional strain on time and resources, there are a range of online tools and platforms that are already being widely used in HE institutions.

Regular practice in a safe environment

Enabling the presentation of content in more immersive and engaging formats, automating marking – even summative assessments – and tracking individual learners’ progress is the formula for success. The Nuffield review found that blended learning, which combines classroom teaching with online tools that encourage immersive, autonomous study, is proven to work – not only for students (by allowing them to learn at their own pace and practice the elements they’re finding the most difficult), but also for teaching staff. It offers more strategic use of classroom time, whether live or virtual; lectures can be centred around more meaningful discussion and deeper analysis, while online tools can be used to reinforce key maths principles.

A study by University of Greenwich found that a blended approach increases academic self-efficacy in the area of mathematics, and also enhances the student experience. The benefits, it said, arise from the combination of allowing the individual mastery of technical skills in the private and stress-free environment provided by the online platform.

Done well, blended maths learning can offer students the opportunity to improve their numeracy ability at their own pace. Online tools that reinforce course principles, nurture students’ maths ability in a clear and scaffolded way, flex to the areas where they need the most support.

Pearson offers a range of digital tools to support blended learning in both maths skills and wider discipline content. Discover the tools to available for psychology, economics, engineering, computer science, STEM subjects and more.