View/download full data on UK institutions’ finances, 2014-15

English universities have entered a new realm in which they must compete for students to survive – and where dangerous beasts lie in wait for those that do not.

The recent removal of the cap on the number of undergraduates that an institution can recruit gives universities the freedom to eat into their rivals’ market shares, but if an institution suffers successive years in which its recruitment decreases then its income will plummet and it will fall to the back of the group – to be picked off by whatever is waiting in the shadows once the government creates its desired “market exit” mechanism for institutions deemed to be failing.

Student controls began to be lifted in 2012, so the latest financial data for 2014-15, gathered by accountancy firm Grant Thornton from UK university accounts for Times Higher Education, already reflect these changes. But the effects will only accelerate in the future, given that the numbers cap was completely abolished only in the 2015-16 academic year.

Richard Shaw, head of education at Grant Thornton, says that the figures show “another solid year, with surpluses that are up on the year before. But I think that masks some variations across the sector.” Some institutions are “taking time to adapt” to policy changes, he adds.

Earlier this year, Madeleine Atkins, chief executive of the Higher Education Funding Council for England, picked out two key factors in the body’s analysis of finances at sector level: “the increased variability of financial performance” and “the risk of underachieving against ambitions for overseas recruitment”.

But what does increased “financial variability” mean for individual institutions? And, amid concerns that government immigration policy is restricting the flow of non-European Union students, how can universities boost the overseas income that they see as essential to cross-subsidising loss-making research activity?

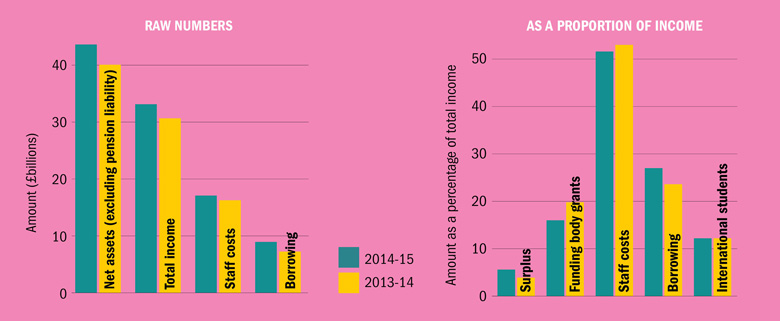

Across UK universities, total income was £33.1 billion in 2014-15, up from £30.7 billion the previous year, the data gathered by Grant Thornton show (see graphs, below). The sector’s collective surplus (before exceptional items) was £1.9 billion, equating to 5.6 per cent of income. That was up from 3.9 per cent in 2013-14 and 3.7 per cent in 2012-13.

But Hefce stresses in its report on sector finances, Financial Health of the Sector, that the increase in surpluses in England was “largely attributable” to a one-off benefit from the government’s Research and Development Expenditure Credits. That scheme, established in 2013, offers tax incentives to large companies to encourage greater investment in research and development. But the scheme has now been amended “so that universities and charities are unable to claim [the credit] in respect of expenditure incurred on or after 1 August 2015”, Hefce notes. So the increased surplus in 2014-15 paints an unduly rosy picture: next year’s surpluses will be lower.

Despite universities’ nervousness about immigration policy, income from overseas (ie, non-EU) student fees rose by 7.7 per cent, from £3.7 billion to £4 billion. But overseas income remained at 12.2 per cent as a proportion of total income, unchanged from the previous year.

Year-on-year comparisons

The data show nine institutions drawing more than 25 per cent of their total income from non-EU student fees (see table, below). There is no surprise in the University of London’s position at the top of the list: 50,000 students in 180 different countries study on the international programmes that are the core of its student offering. It is accompanied by another five London institutions at the top of the list, as well as three regional institutions – the University of Sunderland, Heriot-Watt University and Coventry University – with London campuses (Heriot-Watt’s is billed as an “associate campus”). If you want to really capitalise on overseas student income, it seems you have to be in the capital.

On general finances and overseas income, UK universities can be usefully compared with those in Australia, the country whose more marketised approach has been seen as a precedent for developments elsewhere, particularly in England.

There, overseas income amounted to A$4.7 billion (£2.4 billion), or 17.3 per cent of total income in 2014, according to Department of Education and Training statistics. Andrew Norton, higher education programme director at the Grattan Institute thinktank in Australia, says that percentage is “up on recent years but below the peak in 2010”, after which the government toughened the student visa regime, before relaxing it again more recently.

So the UK, as a whole, is less reliant on overseas income than Australia. Nevertheless, some UK universities are far more reliant on it than any individual Australian institution is. Two of the latter – RMIT University in Melbourne and Macquarie University in Sydney – draw a quarter or more of their income from overseas students: 28 per cent and 25 per cent respectively. This is considerably less than Sunderland, the second most reliant UK university on non‑EU student fees, which derives 34.8 per cent of its income from this source.

As well as its London campus and a “big international intake” on its home campus, “a very high proportion” of this figure is attributable to Sunderland’s involvement in transnational education (TNE). Currently about 9,000 students study franchised Sunderland degrees in their own countries, according to Judith Green, director of marketing and recruitment at the institution. Moreover, the Home Office’s toughening of visa rules has seen some “big declines in markets that we regularly recruit from” for UK-based courses, making TNE all the more important to Sunderland’s strategy.

Green admits that it is “very competitive”, because “everywhere we go there are people looking at TNE as a silver bullet in [their] international business [strategies]. But we’ve been around in it for so long now that we have a very firm foothold across a range of partners across a range of countries.”

Richard Williams, principal and vice-chancellor of Heriot-Watt, also points to TNE as a factor in his institution’s high non-EU income, alongside recruitment to its campuses in Scotland, Dubai and Malaysia. Heriot-Watt has more than 18,300 students worldwide “studying at learning partners or by distance learning” in areas including “petroleum engineering and construction industry professions, as well as the Edinburgh Business School MBA, which is one of the largest online programmes of its kind in the world”, Williams adds.

TNE clearly has appeal given the concerns over visa policy. But while both Sunderland and Heriot-Watt emphasise the close attention that they pay to ensuring quality, the scandals generated by the University of Wales’ mass franchising of its degrees in about 30 countries highlight the reputational risks. In 2014-15, the institution ran a deficit of £1.8 million, amounting to 23.1 per cent of its income, while in the process of being merged with Swansea Metropolitan University and one of its own constituent colleges, Trinity Saint David. The merger, announced in 2011 in the wake of the franchising scandal, is due to be completed next year.

Universities most dependent on non-EU students

| Institution | Overseas income as % of total income | |

| 1 | University of London | 37.0 |

| 2 | University of Sunderland | 34.8 |

| 3 | London School of Economics | 30.0 |

| 4 | Heriot-Watt University | 29.9 |

| 5 | City University London | 29.6 |

| 6 | Royal College of Art | 29.4 |

| 7 | University of the Arts London | 29.1 |

| 8 | Coventry University | 26.4 |

| 9 | Soas, University of London | 26.1 |

| 10 | University of St Andrews | 21.7 |

In the standard overseas market, UK universities also face fierce competition, especially from institutions in countries with more student-friendly visa policies, such as Australia. According to Norton, Australian universities “will want to expand their international enrolments if they can”. Reasons include the need to subsidise research and fund above-inflation staff pay rises: “It was these kinds of cost pressures that helped trigger the original international student boom, and international students remain one of the few areas in which universities can make substantial profits,” Norton says.

Phil McNaull, chair of the British Universities Finance Directors Group, cautions that there are limits to overseas expansion: “It’s pretty clear that some of UK universities’ ambitions to recruit overseas students exceed the market supply. If you look at any industry where there are a number of organisations competing for customers, be it local or overseas, the same will apply. You really need to be seeking either to grow the market or to take market share from your competitors – and the same applies to overseas students.”

The number of non-EU students starting courses fell by 1 per cent in 2014-15, according to Higher Education Statistics Agency data.

McNaull, who is finance director at the University of Edinburgh, also notes that “regulation and government policy are quite volatile in this area. You could lose your ability to recruit overseas students overnight.”

That is exactly what happened to London Metropolitan University in 2012, when its licence to recruit overseas students was revoked by the Home Office. Although the university won back its full licence in 2014, the impact of the revocation is still being felt. It is one of the factors that explains why the institution returned a £5.5 million deficit in 2014-15, according to John Raftery, London Met’s vice-chancellor.

At 4.9 per cent of its income, London Met’s deficit was the highest of any English public institution in 2014-15, the data gathered by Grant Thornton show. Raftery says “changes in government policy” were factors in the failure of the institution’s overseas income to bounce back as expected after it won back its licence. He is referring to the visa crackdown on students coming from perceived “high-risk countries” and the lowering of the visa refusal rate threshold, such that when more than 10 per cent of an institution’s overseas students are refused a visa, it faces having its licence to recruit revoked.

“We have to be very, very risk averse in admitting students from overseas. We’ve pulled out of some countries because the risks are too high,” says Raftery. He adds that the Home Office has been “very clear about the policy intention to bring the brightest and best students from around the world into the top selecting universities. That’s actually what’s happening. That’s a £30 million-a-year income stream that really doesn’t exist any more for London Met. Not just London Met but other institutions, too: certainly post-92s.”

On the home front, the emergence of a competitive market in student numbers in England has left London Met with the biggest fall in UK/EU student acceptances of any English institution since 2011, the last year before the lifting of student number controls began, a Times Higher Education analysis of Ucas figures has shown. The number of students accepting places at London Met fell from 6,870 in 2011 to 3,490 in 2015; if acceptances are any reliable guide to enrolments, the institution will be seeing enrolment numbers at half of what they were a few years ago.

Universities living most comfortably within their means

| Institution | Surplus/deficit before exceptionals as % of income | |

| 1 | Norwich University of the Arts | 23.6 |

| 2 | Institute of Cancer Research | 20.9 |

| 3 | Edge Hill University | 19.1 |

| 4 | University of Huddersfield | 17.9 |

| 5 | Imperial College London | 15.2 |

| 6 | Leeds College of Art | 14.9 |

| 7 | Bishop Grosseteste University | 14.1 |

| 8 | University College Birmingham | 13.4 |

| 9 | University of Oxford | 13.4 |

| 10 | Birmingham City University | 13.3 |

Raftery says the fact that London Met’s deficit is less than it originally forecast is “really good news for the institution”. And he says that “many organisations over the short- to medium-term run deficits when they are investing in their future”, pointing out that London Met is spending £125 million on a plan to consolidate its activities on a single site. He also describes the university as “one of the very few to have no debt”. Nevertheless, “London Met and some other institutions in London, post-92s, are also seeing a fall in home students. We need to front up to that.”

Still, he is “not at all against the removal of student number controls…Over the whole sector it [imposes] a pressure on institutions to raise their game continually. That’s not unreasonable. Students will benefit nationally and a particular institution which is short-term underperforming will not benefit. I’ve come into London Met and that’s how it was.”

Raftery says that since he took over in August 2014, programmes have been introduced to improve London Met’s performance in the National Student Survey, and on graduate employment and drop-out rates. As a result, the institution had the biggest rise in graduate employment in the sector last year, according to the Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education survey, Raftery says.

But “as income falls – and it has fallen with student numbers – I’ve got to keep our cost structure in line”, he adds. The university “isn’t a business, but it has to be run in a business-like way”. And, across the sector, “those institutions where numbers are falling are going to have to consolidate and make cutbacks. That will be investment and jobs, in line with their income.”

As well as the University of Wales and London Met, those larger, non-specialist institutions that ran significant deficits in 2014-15 include the University of Aberdeen (whose £6.2 million deficit amounts to 2.6 per cent of its income), Queen Margaret University (£2.7 million; 7.1 per cent), which has been funding the construction of a new campus, and the Open University (£7.2 million; 1.7 per cent), which has been hit by the collapse in part-time student numbers.

At the other end of the scale, Edge Hill University has the highest proportional surplus of any larger UK higher education institution, amounting to 19.1 per cent of its income (or £23.6 million). John Cater, Edge Hill’s vice-chancellor, says: “With continued threats to public funding and rapid changes in government policy likely to affect all universities, we believe that these surpluses provide a degree of insulation against future uncertainty, and enable the university to continue to invest for the future.”

Edge Hill regularly figures at the top of the pile on annual surplus figures, this year edging out another consistent big hitter, the University of Huddersfield, whose £27.3 million surplus amounted to 17.9 per cent of its income. Also in the top 10 for surpluses are research giants Imperial College London (15.2 per cent; £148.6 million) and the University of Oxford (13.4 per cent, or £191 million) – thanks in no small part to the Research and Development Expenditure Credits.

Of the 159 institutions in the THE analysis, 144 returned a surplus, compared with 143 out of 160 that did so last year. And 52 – 32.7 per cent – achieved a surplus of more than 6 per cent. This compares with 55 per cent of Australian institutions, according to a Grant Thornton report on Australian sector finances. In Australia in 2014, “the sector-wide surplus of A$1.8 billion represented 6.6 per cent of total income”, the report says. If the UK’s figure of 5.6 per cent in 2014-15 does indeed fall away following the abolition of the research credits, that would leave Australian universities looking significantly healthier.

Richest universities

| Institution | Net assets (excluding pension liability) £’000s | |

| 1 | University of Cambridge | 4,000,000 |

| 2 | University of Oxford | 3,019,300 |

| 3 | University of Edinburgh | 2,003,278 |

| 4 | Imperial College London | 1,363,800 |

| 5 | University of Manchester | 1,027,257 |

| 6 | University College London | 1,020,394 |

| 7 | King’s College London | 910,941 |

| 8 | University of Birmingham | 870,788 |

| 9 | University of Sheffield | 869,800 |

| 10 | University of Leeds | 806,435 |

On general challenges in the UK, Grant Thornton’s Shaw says that while “inflation is eroding the benefit” of the recent trebling of tuition fees to £9,000, “at the same time you’re seeing the cost of employing staff increasing, be it National Insurance and other tax changes, further increases to pension contributions or the forthcoming apprenticeship levy”.

For his part, the BUFDG’s McNaull believes that the UK sector is “currently in quite a good position”, as “institutional management have anticipated and responded well to the changing external environment”. In England, “surpluses had to grow as the amount of reliable income from government dropped” – although the UK sector “has been relying increasingly on overseas student income cross-subsidising other activities, particularly research”.

That could be a problem if visa policy does indeed drive down overseas numbers just as the government is ratcheting up the marketised environment in which it now expects English universities to compete. On top of the abolition of student number controls, the teaching excellence framework will add to the competitive pressures by shifting students towards “higher quality” courses and away from “lower quality” ones. And in addition to the creation of “market exit” mechanisms, last month’s White Paper confirmed that “market entry” will also be facilitated to bring in more private and other providers. All this means that the “financial variability” among institutions noted by Hefce will inevitably increase.

McNaull offers one particular note of caution on the future. By bringing in more private providers, he warns that the Westminster government “could damage an integrated university offering, which has teaching, learning and research – which is what a university does. The danger is you separate out elements of that business model.”

He says that private providers “will not be interested in research that makes a loss. If you introduce, in an uncontrolled way, private providers into a sector which operates a cross-subsidy model to maintain the critical research infrastructure that the UK is famous for, there is a danger that trying to achieve that at indecent speed might damage the UK higher education sector.” Nor would the rest of the UK necessarily be immune from the consequences of English policy, given the tendency of politicians to adopt measures “seen to be successful” in other jurisdictions, he adds.

“Universities are very complex organisations. We need to be careful if we start tinkering with them by introducing unrestrained market forces,” McNaull concludes.

Private providers seeking to enter the sector in a bigger way, of course, see things differently. They argue that universities need to be exposed to competitive pressures to improve their efficiency, drive down tuition fees and promote innovation in teaching methods.

What impact all this will have on university balance sheets, and on the jobs of university staff that hinge on these balance sheets, remains to be seen. The path is heading into unknown territory – and there appear to be some glinting eyes watching from the undergrowth.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: It’s a jungle out there

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login