The canteen at HMP Isis is no genteel tearoom, but today it could be mistaken for one. Staff and family members of inmates at the young offenders’ institution mingle among tables covered in white cloths, helping themselves to items from the buffet prepared by prisoners on the institution’s catering course. Emily Thomas, the prison governor, recommends the jam-and-cream mini-scones.

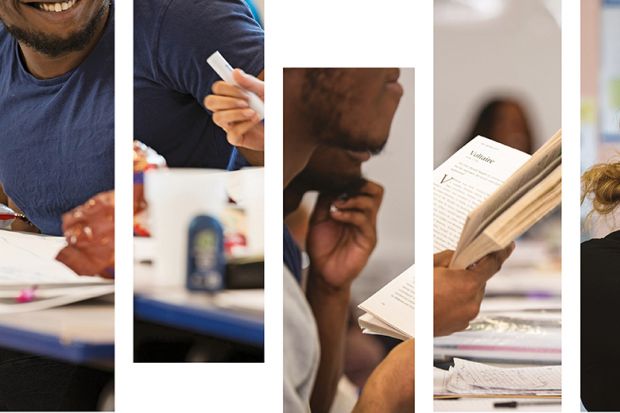

Meanwhile, all the chairs have been turned to face the front of the room, in readiness for the eight philosophy presentations to be given by young offenders. The assessment of these, by academics from Goldsmiths, University of London, will count towards their final Extended Project Qualification, equivalent to half an A level. The academics’ responses, at the end of each presentation, will help the students to clarify their essay questions; 5,000 words must be submitted to complete the EPQ that some of the prisoners hope will bolster a future university application.

HMP Isis is located in south-east London, not far from Goldsmiths. Although the university has plenty of experience teaching former inmates through its well-established Open Book programme, it started teaching inside prisons only last year, beginning with a successful 10-week pilot programme covering social sciences. The male inmates are all between 18 and 30, so they fall into the typical age range for students. However, they have a variety of prior education levels, to which the courses must be able to adapt. Learning alongside the prisoners are current students from Goldsmiths, taking extra credits or on access courses.

Thomas is very impressed by the response to the programme from her inmates. “They are avid learners, which has been very exciting to see,” she says. “I wanted to get something like this to happen because it’s aspirational – there tends to be a focus on vocational training in prisons, which is important, but this is something different.”

Nervous anticipation builds in the room as the start time for the presentations approaches. Each one is the culmination of 10 weeks of hard work, at the beginning of which many of the prisoners admitted to having known nothing about philosophy. The learning curve has been steep. But after the first few presentations are delivered with confidence, everyone starts to relax a little and starts scribbling down notes and thinking of potential questions.

Ursula Blythe, the tutor who led the course, is a philosophy master’s student at UCL and is herself someone who came to higher education later in life. She completed an access course and then a BA at Goldsmiths, where she first became involved with Open Book.

She chose, in the course, to look at the representation of race, religion, gender, sexuality and disability in society, as a starting point for asking philosophical questions. Accordingly, many of the presentations explore religion, morality and life after death. One queries why people believe in God and examines the “first cause”, or “cosmological”, argument for God’s existence (the need for a supreme being to cause the universe to exist). In considering Descartes’ theory of dualism (the separation of mind and body), another encourages the audience to identify whether they are dualists or physicalists by a show of hands.

“The learners are mainly black and ethnic minority young men, so I thought it would be worth reflecting on identity within UK society,” Blythe explains. “Raising awareness of themes such as disability and sexuality helped to fuel debate and engender a sense of empathy. I wanted to motivate the learners to see themselves as active thinkers and budding philosophers, which seemed to work really well.”

One prisoner-turned-philosopher, Mo, poses the question: “Does capitalism provide a basis for morality and social security?”

“I’ve really changed my thinking on it,” he tells Times Higher Education . “I started out just thinking that capitalism was what we’ve got, and that it is the best system, but now I’m not so sure. I haven’t decided yet what the answer to my question is, but the process has made me realise that everything can be questioned: you have to go into philosophy with an open mind.”

Mo’s favourite philosopher is Immanuel Kant, and he insists that what he has read during the course will be useful in his everyday life, both now and when he is released. “It’s definitely given me a different perspective. I used to think money was the only thing that mattered; it didn’t matter how I got it. Now I feel like other things are important.”

It is hard to overstate the genuinely transformative impact that the course seems to have had on the group. One of the speakers says that by taking part in the course he realised that everything could be questioned and that his opinion was important. Another found that, as a gay man, he identified with the writings of Michel Foucault, and observed that a discussion on the topic of sexuality had led to a shift in the wider group’s attitudes.

All this will be music to the ears of those who went to a great deal of trouble to set up the course. One of those is Jo Sharpe, an education officer at Isis. Every week, she says, she faced a battle to find the resources and space needed. This is despite the fact that there was only capacity for 12 inmates, out of a prison population of 630; the selection was made by interview, and the 30 unsuccessful candidates had to make do with a place on the waiting list.

The appetite for higher-level non-vocational learning is evidently keen among offenders. However, amid cuts to prison budgets and reductions in staff numbers, it would be easy to assume that the provision of such learning would not top many institutions’ list of priorities.

According to Rod Clark, chief executive of the Prisoners’ Education Trust (PET), the budget for education in prisons has been saved from cuts, but institutions are often too short-staffed to facilitate lessons. “This means that prisoners have been locked in their cells much more than they should – sometimes for 23 hours a day,” he says. “Therefore, even if teaching could happen, the prisoners are not being [released from their cells] to get there.”

Despite such challenges, he says, there are currently about 120 university-prison partnerships, many of which were established in the past two years. According to the charity’s database, 23 of these were launched in 2017, involving a variety of institutions, from small, new universities to large research-intensives – and, of course, the Open University.

It is nothing new to find teachers and academics working inside prisons; various types of ad hoc education have been on offer to prisoners for years. But formal, university-led lessons such as the programme at Isis have developed only relatively recently in the UK, Clark says. The model that Goldsmiths is using – of undergraduate students learning alongside prisoners – was pioneered in 2014 by Durham University with its Inside/Out criminology module. The following year, the University of Cambridge launched a similar programme, called Learning Together.

Indeed, initiatives by criminology and law departments lie at the root of many university-prison partnerships, as there is an obvious benefit for mainstream undergraduates in the opportunity to experience prisons and to learn from prisoners.

Hannah Thompson, a third-year criminology student at the University of Manchester, says that her department’s partnership with HMP Risley in Cheshire, which started last September, has been very useful.

“For me, criminology is more than a degree. I want to become a researcher myself, and I feel it’s not enough to just go to lectures and seminars to become a criminologist: you have to go out and work with the groups of people you come across in your readings,” she says.

She has been struck by how much she has in common with the inmate-students she has worked alongside. “A lot of the guys are a similar age to me, and we agree on many things, particularly stuff relating to how bad the prison system is – it’s amazing to have what you have read confirmed by them.”

Shadd Maruna, a professor of criminology at Manchester, suggests that learning inside a prison motivates undergraduates such as Thompson to go the extra mile in their studies. But perhaps more importantly, he feels that it helps them to “put a face to a name”, to personalise the effects of the criminal justice policies that they explore in books and seminars. He believes that students on other courses that grapple with social problems could also benefit from being taught in prison because offenders are likely to be at the sharp end of many of the issues that they cover.

This feeling is echoed by Morwenna Bennallick, a research officer with the PET and a PhD student researching prison education culture at Royal Holloway, University of London. Having led a course inside HMP Feltham, another young offenders institution in London, she is adamant that there are educational and research benefits for universities across a variety of disciplines.

“What we are seeing more this year is a greater range of subjects being taught – creative writing, drama, psychology, social research and so on,” she says. “In those cases, the benefit [to mainstream students] is less clear at first, but it’s easy to underestimate just how important it is to get a different perspective from learners experiencing a completely different institution from your own university – especially if you are studying a creative or social sciences-based subject.”

She reports that doctoral students from other departments were also keen to teach alongside her at Feltham. “They wanted to learn how to explain quite complex philosophical ideas to people with different perspectives. That in turn helped them to clarify their arguments: the benefit goes both ways.”

According to Bennallick, there is a strong commitment to such programmes at senior levels across the sector. “There are a number of different movements in the sector that this work speaks to, such as widening participation. We’ve seen more universities talk about developing Level 3 access courses, too; so there is a chance for offenders to continue education once they leave prison, and perhaps apply to university.”

But both Bennallick and Maruna acknowledge the challenges from the academic side of establishing partnerships. “It takes a very progressive and willing prison to sign up,” Maruna says. “You are essentially dealing with two large bureaucracies, and the staff at the prison need to be open to the idea – and not short-staffed, or angry at being short-staffed, preferably.”

Money is also an issue, he adds: universities typically do not have the extra funding to buy out the time of the academics involved in such programmes. “At Manchester, we were able to apply for funds from the Centre for Higher Education Research, Innovation and Learning (CHERIL). But other academics have said that they are doing the work in addition to their regular workloads,” he says.

Still, there is no end in sight to the expansion of university-prison partnerships. And if the experience of the Isis inmates is anything to go by, the benefits seem likely to far outweigh the practical difficulties involved. Before the afternoon is over, Blythe, the course leader, is applauded by her students for her efforts. Many declare that her lessons will stay with them for life.

“Skills such as critical thinking are so crucial,” Blythe says afterwards. “I sometimes feel like higher education – and then philosophy – saved my life, and I hope it’s the same for them, too.”

Locked-in learning: In this environment, prisoners and undergraduates all pull together

The experience of delivering higher education in a high-security prison is both very challenging and extremely rewarding.

The challenge lies not so much in overcoming the intimidation that you might expect to encounter from prisoners. In our experience of teaching a third-year criminology module at HMP Full Sutton in Yorkshire last year, all the concerns around safety and security that we discussed at length during planning proved to be merely theoretical. Prisoners are no more confrontational in class than the standard Leeds-based undergraduates who take the module on penology alongside them.

Although the campus-based students entering the prison were understandably nervous about coming into a penal institution, that was outweighed by their excitement about the prospect of having their preconceptions challenged in a way that they had never experienced before. The concerns for the prison-based students should not be underestimated either; they too were apprehensive about how they might be perceived by “outsiders” entering the prison. For us, creating this opportunity was about replicating the university experience in an environment that enables the two groups of students to come together and break down social barriers in the process.

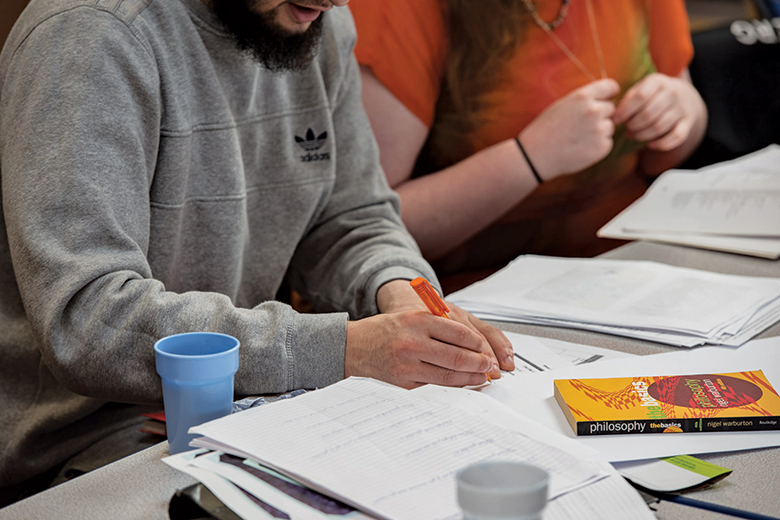

The challenge is primarily pedagogical. When lecturing, we tend to stick to what we know, making liberal use of projectors, online learning technologies and esoteric jargon, encouraging students to independently explore the material available and draw their own conclusions. But prisoners cannot do this because they lack the unrestricted access to online learning resources.

But necessity is the mother of invention, and this narrowing of options creates a space for innovative thinking about pedagogy. You have to strip learning back to its core elements: engaging thoroughly with academic literature and creating opportunities for insightful discussion and debate. You need to provide all the base knowledge that you want explored and use small-group teaching to help the students understand how to process the literature into their own knowledge through critical thinking and discussion. This creates powerful learning experiences.

Another concern that we had before the course began related to the wide disparities between the students’ educational levels. Nevertheless, we wanted everyone to have the same learning experience as far as possible. So we provided each student with a module handbook to guide their study, and gave them a reading pack with all material that they were required to read in advance of the taught sessions. All the students completed the work required, and this had unexpected benefits for the university-based undergraduates. In the absence of the online learning and resources they are used to, they immersed themselves in their hard-copy materials, developing a deeper understanding and appreciation of research, theory and key concepts through engaging with the primary research.

The prison-based students were just as engaged – if not more so. In some cases, they were slightly less able to express their thoughts academically – but reading the literature enabled them to overcome that, too. In the event, all students attained at least an upper second-class grade in the module, with four of the prison-based students attaining a first-class grade.

Many of the students in the collective cohort described their experience of the course as life-changing, particularly in relation to their conceptions of self and others. All the students had a profound impact on each other, willingly helping their peers to find their own voices, gain confidence and realise that they all had something to offer others: whether academic knowledge and understanding, or support more generally.

The provision of further Leeds Beckett courses at Full Sutton is currently being piloted, with a view to providing more of them within the next three years, across a number of subject areas. This will be to the benefit of both students on campus and those in hard-to-reach places in our community.

Helen Nichols and Bill Davies are senior lecturers in criminology and co‑lead the Prison Research Network (PRisoN) at Leeds Beckett University.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login